Transportation

Harold

Harold is a White, 56 year-old single man living in a close-in suburb west of Indianapolis. Since he lost his job as a driver for a delivery company three years ago, he has worked various part-time jobs. Currently, he’s a bus driver for a local school, and he works part-time as a server at a sit-down chain restaurant near his home. His total income is a little under $30,000. He owns a car but uses it as little as possible. Both of his part-time jobs are within easy walking distance of his home, and he carpools with a friend who lives nearby for trips to the grocery store. Harold also has a bike and uses it for exercise and for short errands. The benefits on his mental and physical health from walking and biking—and a series of costly, unexpected car repair bills over the past year—have led Harold to think about selling off his car. One obstacle is the fact that he has a son, daughter-in-law, and two grandchildren in the city’s northern suburbs. It takes 20 to 30 minutes to visit them by car. He could get there by public transit, but it would take about two hours.

Through another friend, Harold recently learned about and was offered a position as server at a restaurant in downtown Indianapolis. Working full time there, he estimates he would make up to $6,000 more (depending on tips) annually than he currently earns with two part-time jobs. Although he’s intrigued by the offer, transportation challenges make it a hard call. By car, the trip downtown from his home is about 20 minutes. But the extra expenses for gas, repairs, and parking would consume a significant share of the extra money he would make at the new job. Alternatively, he could take public transit. But the walk to and from his home to the bus stops, plus the commute time, would add up to more than an hour each way. As a result, one of two things will happen if he takes the new position: car expenses will eat up much of his additional income, or he will spend much more of his free time riding a bus, especially if he sells off his car and uses public transit to visit family. Yet the status quo also has very real downsides. Most notably, Harold fears being stuck in a cycle of relatively low-paying, part-time jobs for the rest of his working life.

- In Indianapolis, approximately 76,000 people age 65 or older live too far away from an IndyGo stop to likely use transit. That represents nearly two thirds of people age 65 or older in Indianapolis.

- Less than one in five older adults in Central Indiana positively rates the ease with which they can use public transportation in their communities.

- In Indianapolis, one in three older adults lives in a neighborhood with minimal or no public transportation service.

- IndyGo plans to improve service through its future service plan (2023-2027). This is likely to help older adults who live along pre-existing routes.

Inadequate Public Transportation

According to the U.S. Department of Transportation, “transportation is essential to many areas of life such as employment, staying connected with family and friends, and access to healthcare.”1 However, many older adults do not have good transportation options beyond driving.

In Central Indiana, older adults find travel by car much more accessible than walking or public transportation. Four out of five older adults report that the ease of car travel is good or excellent in their communities, while only 56 percent say the same about walking and 18 percent about public transportation.2 Additionally, 42 percent of older adults said that safe and affordable transportation is not available in Central Indiana.3

This is particularly important for households without a vehicle, and the 2021 five-year American Community Survey estimates that one in 10 households with a household member older than age 65 has no vehicle. Furthermore, access to vehicles varies by housing tenure. One third of renter householders age 65 and older have no vehicle, compared to only five percent of homeowners.

Public Transportation Use by Older Adults

Indianapolis has a substantial public transportation system and in 2019, its fixed-route ridership was 9,244,855.4 Analysis of the 2017 IndyGo On-board survey data shows that one quarter of bus riders are adults age 50 and older. Some of these riders use public transportation for commuting, but others also depend on it for shopping, social visits, and other quality-of-life destinations. For people age 50 to 64, 46 percent of public transportation trips starting from home were for work, 12 percent were for shopping, and 29 percent were for social, religious, or personal business. People age 65 and over make 21 percent of their home-based transportation trips to work, but 46 percent are for social, religious, or personal purposes and 20 percent are for shopping. In general, medical appointments are not a common trip destination for IndyGo riders, but keeping medical appointments is important to an older adult’s health. Although only a small share (7 percent) of home-based trips using IndyGo had a doctor or health-related destination, ridership for health-related purposes increases with age. More than one in 10 (12 percent) older adults age 50 and over whose transportation trips started from home traveled to a doctor’s office or other health-related location.

Older public transportation riders do not use the bus as frequently as daily commuters but still take the bus at least once a week. One sixth of riders age 65 and older use public transportation one to two times per week, and over one third use it three to five times per week. Many riders agd 50 to 64 use it almost daily, as 62.4 percent take the bus between three and seven times each week. However, public transportation is often only easily accessible to those who live near a public transportation service. Unfortunately, while some older adults live in neighborhoods with good public transportation service, most do not. Approximately 76,426 adults age 65 and over in Indianapolis live farther away from bus stops than many are likely willing to walk—about 1,200 feet, or just under a quarter mile, based on the 75th percentile of distance traveled to bus stops by IndyGo riders age 65 and older. IndyGo riders age 65 and over, on average, also tend to have the shortest distance from their point of origin to the bus compared to any other age group, illustrating potential limitations in their mobility.

A transit service density score (shown in the map below) is another way of quantifying transit service available to a neighborhood. It is calculated as weekly revenue miles per square mile and ranges from zero (no transportation services) to over 1,000 (high transportation service).5A greater number of older adults tend to live where transit density is the lowest.

The greatest number of adults 65+ who are likely too far from transit live in the more suburban or rural areas of Marion County.

Adults age 65+, on average, travel the least distance from their point of origin to a bus stop compared to any other age group.

There are fewer adults age 65+ living in the urban center

Transit density is the greatest in the urban center, where there are fewer adults age 65+

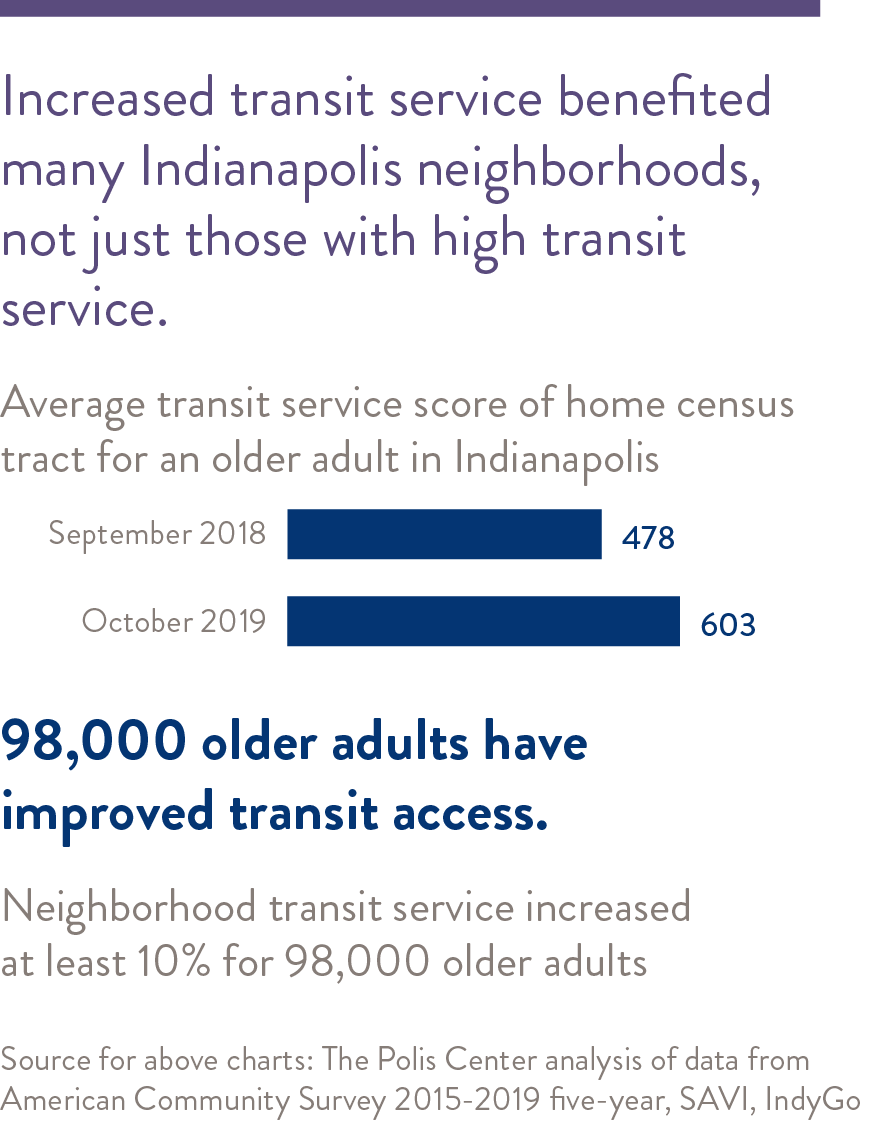

In 2019, the City of Indianapolis invested in significant public transportation improvements, which led to increased service, including for older adults who live in Marion County. Twenty more census tracts had improved service in October 2019, compared to 2018. As a result, 15,000 additional older adults now live in high public transportation service neighborhoods. Increased public transportation service broadly affects adjoining neighborhoods, not just those with high levels of service. Nearly 98,000 older adults now reside in census tracts where service increased by 10 percent or more. In Marion County, the average older adult experienced a 26 percent improvement in service. This was accomplished by increasing the frequency and operating hours of local routes, as well as adding bus rapid transit via the Red Line. IndyGo plans to continue increasing local bus service with greater frequency and two additional rapid transportation lines through their proposed 2023-2027 future service plan.6 IndyGo will particularly target transit critical population zones with increased frequency, improving the reach of 15 minute or better service for minority communities, zero vehicle households, and low-income households. While this will likely improve access for older adults, this future service plan is focused along pre-existing routes and will not expand access to less urban areas in Marion County where older adults are more likely to reside.

Similar to every transit agency in the country, IndyGo experienced a 46 percent decline in ridership between February 2020 and February 2022, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.7This drop in ridership negatively impacted IndyGo’s revenue, leading to a reduction in service frequency. Additionally, the shortage of bus drivers has been a continual challenge, with IndyGo being around 100 drivers short of its operating goal for most of 2022.8 The reduction in service frequency impacts older adults reliant on public transportation, causing longer travel times and limiting accessibility to complete multiple tasks in a single trip.

IndyGo ridership has fallen sharply during the pandemic, but is beginning to rise again in recent months in 2022.

Community Needs

Central Indiana households having trouble acquiring transportation have the option of dialing 2-1-1 to connect with needed services. In 2021, there were 1,032 calls to 2-1-1 from older adults requesting transportation assistance 9 There is a marked difference between age groups. For example, only 21 adults age 70 and above called about ride app services in 2021, while 539 adults age 60-69 did. In general, ride app services made up the bulk of calls, at 54 percent. Marion County by far received the most 2-1-1 calls for transportation needs in 2021 for adults age 60 and over compared to other counties within Central Indiana. 10

Community Perspective

According to focus group participants across Central Indiana, transportation is important for maintaining independence. 11 Those who can access it enjoy the activities it allows them to do, while those who cannot feel their independence was curtailed. Across the Central Indiana region, participants report utilizing various means of transport. Some drive themselves or are driven by others, some utilize rideshare or shuttle bus programs, some who live in Indianapolis ride public transportation and others walk. The type of transportation used and the frequency with which it is used depends on affordability, accessibility, and a variety of other factors. One participant drives himself and other older adults out to eat, while another who owns her own vehicle found that paying for its ongoing maintenance problems was challenging and stressful. As a part of the aging process, driving at night is no longer safe for some and the lack of accessible parking is a deterrent for others when driving to locations they frequented in the past. The roundabouts in Carmel were mentioned as confusing and difficult to navigate by one participant. Other older adults relied on family or friends to drive them, which is helpful but does not always allow these older adults to be as independent as they wish.

While rideshare programs permit focus group participants to go anywhere they wish, these programs are expensive, rely on technology that some do not know how to use, and are viewed as potentially unsafe by others. Shuttle bus programs, such as those through medical providers, senior centers, CICOA Aging and In-Home Solutions (CICOA), and IndyGo’s Open Door program, are options that are affordable to many participants and are useful for going to medical appointments and sometimes grocery shopping. A few participants indicated that the nominal fees charged for some of these services are not within financial reach for them, and hoped for more affordable, free options. Most of the services mentioned by older adults do not operate outside Marion County, making it difficult for older adults who must travel to the suburbs for medical, personal, or social reasons. Those transit options that do cross county lines often require reservations in advance. Depending on where they lived, participants had different opinions on how accessible public transportation was. Some find it convenient, while others had difficulty accessing it. One participant mentioned how much she enjoys the new transit center downtown, while another one noted that it is difficult to navigate the stairs on the bus. Walking is also enjoyed by some as exercise or transportation; however, poor weather can make this prohibitive, particularly as ice and lack of snow clearance make sidewalks, bus stops, and curbs dangerous to navigate.

Filling the Gap

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires public transportation providers to provide paratransit to eligible individuals. 12 Paratransit is a publicly-funded, low-cost ridesharing service available by request. IndyGo’s paratransit service, now called IndyGo Access, operates seven days a week throughout Marion County. According to IndyGo, eligibility is based, “...on the effect the disability has on the applicant’s functional ability to board, ride and disembark independently from a fully-accessible local transit vehicle. The accessibility of the regular local transit service and the environmental and architectural barriers within the service area are also considered.” 13

IndyGo conducted an evaluation of its paratransit services in 2020 and found that one in five trips are made by individuals whose start or finish location has the following characteristics:

- is in the outlying parts of the county,

- is outside the ADA-required zone, and

- has an average trip distance of 12.5 miles.

This average trip distance is three miles longer than the average distance of peer paratransit agencies. 14 This is evident when looking at expenditures per rider data from 2021 for each transit agency, where IndyGo Access had the greatest cost per rider compared to other urban demand transit services in Indiana and most other transit services throughout Indiana in general. However, when looking at a cost per vehicle mile traveled basis, IndyGo Access is much more on par with other services, and is even less than the Indianapolis fixed route system (IndyGo). This illustrates how many more vehicle miles must be traveled per IndyGo Access rider.

All eight Central Indiana counties have paratransit/door-to-door service, operated by either a public transportation authority or a senior services agency. Each of these programs provides transportation within the boundaries of their respective counties. Older adults who are dependent on these services but require inter-county transportation must transfer from one county service to another at one of 19 possible transfer points across Central Indiana. Fourteen of those transfer points are between IndyGo and one of the surrounding door-to-door services. These demand response services are often the most costly on a per-rider basis but are essential for many older adults in Central Indiana.

There are several transit services within Central Indiana targeted toward older adults and those with limited mobility. CICOA’s Way2Go service provides scheduled rides within Marion County for a fee of $5.00 per ride. Medicaid may cover the cost of this ride service when the trip is to a medical appointment. CICOA also provides shuttle services from certain apartment complexes within Marion County to major destinations such as banks, grocery stores, and shopping centers. My Freedom is a voucher program available across the whole region that allows persons with disabilities to purchase up to 15 vouchers per month for $6.00 each and use them as payment in any of the door-to-door providers in Central Indiana. These services were typically described as affordable by focus group participants, but because service is usually restricted to within county boundaries, these services are rarely used for regional trips. Key informants mentioned the main downturn of these services not going outside of county boundaries was their restriction of participants being able to use them to attend medical appointments. 15 Similarly, IndyGo has minimal service outside Marion County. The public and nonprofit transportation services available to older adults in Central Indiana still leave a gap in navigating the region at large. However, efforts are currently underway throughout Indiana, such as through Health by Design, to improve connectivity and accessibility to transit services between different agencies. To learn more about some of the factors that lead to gaps in transportation service for rural older adults, please read “Highlighting Equity” below.

Ride app services made up half of 2-1-1 transportation calls from adults age 60 and older in 2021 within Central Indiana.

Almost all 2-1-1 calls from older adults related to transportation needs in Central Indiana came from Marion County residents.

Expenditures per rider are greater for demand services in general relative to fixed route services, although demand services are especially critical for older adults.

Rural older adults have less access to transportation services

Across the U.S., public transportation is generally less available for rural residents than for urban residents. One third of rural areas have access to public transportation, compared to nearly three-quarters of metro areas.16 Because one in five (21 percent) older adults in Central Indiana lives in rural areas, this can cause disparities in access to transportation for these older adults, which can affect their overall health and well-being. Additionally, even in more urban areas such as within Marion County, approximately 76-thousand older adults live too far from a fixed route bus stop to likely use it. Below are factors that can influence the lack of access to transportation for rural older adults.

Organizational factors: Lack of vehicles and resources for rural transportation services

One study that interviewed key informants in all 50 states about rural transportation challenges found that the lack of vehicles and personnel was the most cited barrier to providing sufficient services. 17 One senior center in Hamilton County states in their senior transportation guide that the Hamilton County Express, which is the only public transportation service to serve the general public in the county, is unable to serve roughly 800 ride requests per month due to a shortage of available vehicles. 18

Community factors: Changing demography in rural areas impacts services

Due to the migration of younger people to urban areas for more educational or career opportunities, older adults are beginning to make up a larger proportion of the population in rural areas. Because of decreased economic opportunities and fewer working-age residents, rural communities tend to have smaller tax bases. Reduced tax revenue means that the local government has fewer financial resources available to support or expand public transportation programs.19 Compounding these difficulties is the fact that rural transit services in Indiana are also the most costly per rider.

Policy factors: Medicaid reimbursement doesn’t fully reimburse the expenses of transportation providers

Medicaid is an important source of transportation for qualified older adults in need of medical transportation. However, Medicaid only reimburses travel that occurs when the patient is in the vehicle. This policy can hurt the overall operating costs of rural transportation providers, as they often must drive more unreimbursed miles to pick up a passenger due to larger distances between businesses and residences in rural areas.20

- U.S. Department of Transportation, “Accessibility,” 2020, accessed February 5, 2021, https://www.transportation.gov/accessibility.

- National Research Center, “CICOA Aging and In-Home Solutions Full Report,” Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (TM) (Boulder, CO: National Research Center, 2021).

- National Research Center, “CICOA Aging and In-Home Solutions Full Report,” Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (TM) (Boulder, CO: National Research Center, 2021).

- IndyGo, “About Us,” IndyGo, accessed February 5, 2021, https://www.indygo.net/about-indygo/.

- Transit service density scores are calculated for each census tract by finding the total mileage of bus service available (including multiple trips on the same route) and dividing that by the area of the census tract. This score rises if trips are more frequent, if operating hours are extended or if more routes are added.

- IndyGo, "IndyGo Future Service Plan" IndyGo, Accessed October 28, 2022 https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/4176f43c5ea54394821e2b58c46b9e2f

- IndyGo, "Transit Planning, Policy, and Performance" IndyGo, Accessed October 28, 2022 https://www.indygo.net/about-indygo/transit-planning/

- Dwyer, Kayla, "IndyGo is proposing a new local bus route map. What to know and how to give input" IndyStar, Accessed October 28, 2022 https://www.indystar.com/story/news/local/transportation/2022/10/11/new-indygo-bus-map-which-routes-could-be-cut-or-changed/69551856007/

- Polis Center analysis of data provided by Indiana 2-1-1, provided by the 2-1-1 dashboard, Accessed October 28, 2022, https://in211.communityos.org/datadashboard

- Indiana 2-1-1 data analysis is provided by the SAVI Community Information System. 2-1-1 is a free and confidential service that helps Hoosiers across Indiana find the local resources they need. When a client calls 2-1-1 for help, this is referred to as an interaction. During each interaction, a client may communicate one or more needs, related to a single problem or multiple problems. When a call is received by 2-1-1, it is placed in one or more categories, depending on the nature of the need(s) expressed by the caller. For example, if a caller requests a referral for a food pantry, a referral for transportation to help get to that pantry, a referral for donated clothing, and a referral for a soup kitchen, the call is identified as a single, unique call related to food needs, transportation needs, and material assistance needs. Even though there are two different food-related needs expressed, the call is only counted as a single call for food-related help. In the 2019 dataset, 75 percent of caller data specified client age, while the remainder did not. In this report, only data with the age of the client (between age 60 and 105 years old) was used.

- Nine focus groups with older adults were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. The focus groups composed of older adults were assembled with the identification and recruitment assistance of community service providers. These focus groups were conducted by researchers, in person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and by Zoom after the pandemic began. The questions asked of the focus group participants were discussed and agreed upon by research faculty and staff.

- IndyGo, “Access,” IndyGo, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.indygo.net/access/

- IndyGo, “Access,” IndyGo, accessed November 1, 2022, https://www.indygo.net/access/

- KFH Group Inc., Palo Consulting Group, and The McCormick Group, “IndyGo Paratransit Operational Analysis Study Final Report,” June 2020, http://www.indygo.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/IndyGo-Final-Report-June-2020.pdf

- Public and nonprofit sector leaders and service providers who are knowledgeable about service systems and issues pertaining to older adults in Central Indiana were identified and interviewed during report preparation.

- Thirty-five key informant interviews with caregivers and service providers were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. Public and not-for-profit sector leaders and service providers who are knowledgeable about service systems and issues pertaining to older adults in Central Indiana were identified and interviewed as key informants during report preparation

- Carrie Henning-Smith et al., “Rural Transportation: Challenges and Opportunities” (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center, November 2017), http://rhrc.umn.edu/wp-content/files_mf/1518734252UMRHRCTransportationChallenges.pdf

- Melissa Gafford, “Transportation for Seniors in Hamilton County: The Definitive Guide,” Shepherd’s Center of Hamilton County (blog), January 14, 2019, http://shepherdscenterofhamiltoncounty.org/transportation-for-seniors-in-hamilton-county-the-definitive-guide/

- James Wood et al., “Older Adult Transportation in Rural Communities: Results of an Agency Survey,” Journal of Public Transportation 19, no. 2 (June 1, 2016), https://doi.org/10.5038/2375-0901.19.2.9.

- Carrie Henning-Smith et al., “Rural Transportation: Challenges and Opportunities.”