Social Wellbeing

The social wellbeing of older adults is dependent on positive, durable relationships and sustained access to community roles and social institutions.

The social wellbeing of older adults is dependent on positive, durable relationships and sustained access to community roles and social institutions. This section of the report discusses social inclusion and purposeful living. Key findings include:

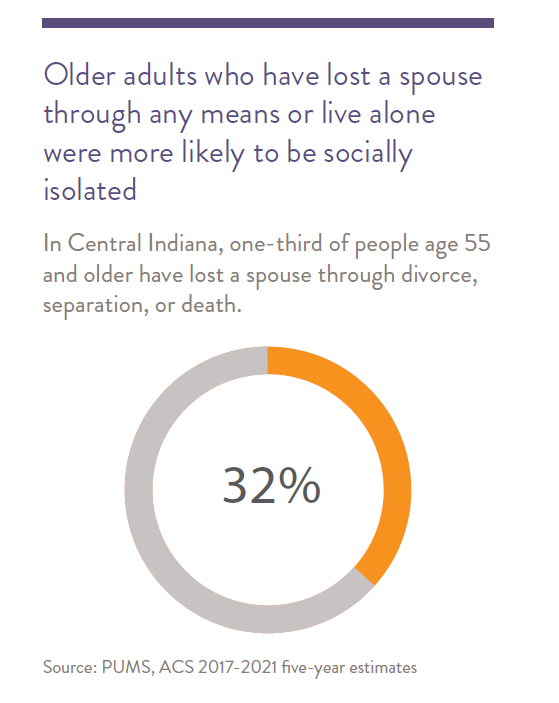

- Two out of five older adult households consist of someone living alone.

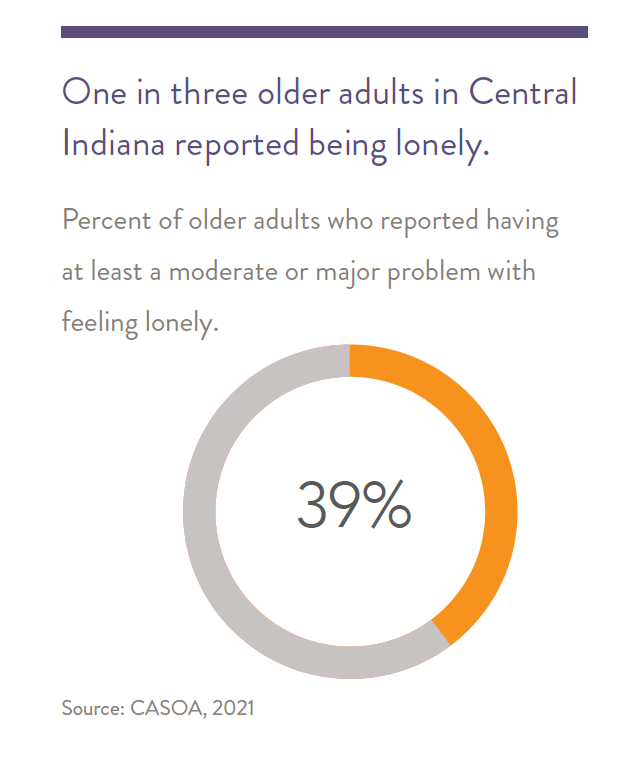

- One in three older adults in Central Indiana report feelings of loneliness or social isolation.

- About half of older adults report having opportunities to participate in community matters, while 14 percent report having used a senior center in their community.

- In Indiana, disability is one of the biggest contributors to isolation in older adults.

- It is difficult for providers to find or reach isolated older adults.

Social Inclusion and Purposeful Living

Social inclusion is the extent to which people have realistic opportunities to take part in society. Most individuals need to feel socially included to find meaning in life.1 2

In contrast, social exclusion is a lack of social roles or access to institutions (e.g., family, church, work), resulting in social isolation. Most can adapt to low levels of social inclusion, but quality of life is diminished. People who are socially excluded in early and mid-life experience more rapid biological aging and lower life expectancy. 3 4

Those in groups who are socially isolated often experience anxiety, depression, and loneliness. Older adults may experience isolation for many reasons. These include retirement, a significant other’s loss of cognition or physical function, a personal loss of health and function that leads to activity limitation, limited opportunities in roles afforded to older adults, and geographic dispersion of families and friends. In addition, early- or mid-life isolation from institutions of learning and employment often results in limited resources throughout adulthood and into later life. For socioeconomically disadvantaged older adults, barriers to inclusion are very difficult to overcome and often occur with additional barriers such as a lack of affordable access to transportation and poor access to various forms of social capital. See section 6 of this report for further discussion of barriers to transportation access.5

Whereas social inclusion includes ongoing access and interaction with other individuals and institutions, purposeful living is more psychological and individual. It involves having goals and pursuing them, and also intentionally accessing various social roles. These roles could include being a volunteer, friend, or worker, each of which creates a sense that you matter to other people in your community. 6 Relative to younger adults, older adults tend to have fewer relationships, but they are often closer and more fulfilling, focusing on quality over quantity. Thus, a loss of these relationships, through moving, or death, can be particularly stressful, impacting health and wellbeing.7

While a sense of purpose changes through the course of life, retirement is a developmental milestone that incurs many changes, not only in daily routine but potentially changes in social networks and an end to an activity many feel gives them purpose. Studies have shown that retirement is a predictor of a declining sense of purpose for older adults.8

Finding volunteer opportunities in the community can replace these losses by expanding social networks and finding a new sense of purpose. This can also lead to the creation of new social roles, where interaction with others creates an interdependency, increasing the sense that one’s life still matters to those around you. Caregiving for others can also create a sense of purpose and belonging but can also be emotionally and physically taxing without sufficient social support.

Feelings of isolation can be a risk factor for depression and cognitive decline.9 A national AARP survey in 2021 found that 27 percent of older adults (age 50 or older) reported feeling isolated, far lower than isolation experienced by younger adults (age 18-49), 44 percent of whom reported feelings of isolation. In contrast to the national survey of isolation, the 2021 Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (CASOA) found that 39 percent of older adults (age 60 or older) in Central Indiana report feelings of loneliness, a significant increase from 33 percent in 2017.10

Risk Factors for Social Isolation and Loneliness

While living alone is a risk factor for loneliness, it is important to note that living alone is not the same as loneliness or social exclusion.

Isolation is more prevalent among older adults experiencing poverty and those with less education, as both situations predispose older adults to smaller social networks (To learn more about the factors that can lead to social isolation among impoverished older adults experiencing poverty, please read ‘Highlighting Equity’ on page 8.11). In addition, the disability that often accompanies age-related chronic illness is a factor in social isolation due to its negative impact on mobility and an individual’s physical and psychological situation.

Older Adult Social WellBeing During COVID-19

The social wellbeing of older adults was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and its various consequences. Several factors contributed to this, such as social isolation, loss of resources, disrupted community services, and reduced job and volunteer opportunities. For example, the most recent CASOA survey for Central Indiana showed a plummeting of perceived volunteer opportunities (rated “excellent” to “good”) from 80 percent in 2017 to 45 percent in 2021, and opportunities to participate in local meetings dropped from 60 percent in 2017 to 33 percent in 2021.

While some national studies conducted during and after COVID-lockdowns showed worsening mental health outcomes from the pandemic, these effects were not found in all studies. While most studies found increases in loneliness, several Indiana studies did not find significant increases in either depression or anxiety among older adults.11 1213 For example, a study of mostly White, college-educated older adults around Bloomington, IN, showed an increase in both loneliness and depression, comparing pre- vs during-COVID lockdowns, but depression levels did not reach clinical significance.14 The same study shows these older adults transitioning to greater use of social media. A separate study of several rural Indiana counties comparing preversus post-lockdowns, found an increase in loneliness, a greater number of ‘unhealthy days’ (mostly due to mental health), and increased food insecurity, the latter caused by the closure of some local stores, decreased hours of regular groceries (including formerly 24-hour stores), and decreased availability of food banks.15

Hodges, et al (2023), found that many older adults experienced anxiety because of conflicting needs—on one hand, the need for socialization, but on the other hand, the need for COVID precautions which limited socialization, as well as limiting access to resources.16 Family members were often the primary source for helping older adults access resources, as well as socialization. This study showed that during COVID restrictions Indiana’s program for Community Health Workers partially filled some of these gaps. Related to these conflicting needs, Coleman, et al. (2022), found that older adults with stronger social networks (bonding capital; see explanation below) had lower levels of loneliness and depression, but also lower levels of compliance with COVID precautions.17 Older adults with broader social networks (bridging capital) had better compliance with COVID precautions, but less protection against loneliness & depression.

Communication technology became a more important resource for older adults’ social connection during the pandemic. A 2021 study suggests that the technology approach of participatory digital co-design can improve older adults’ well-being.18 Co-design is when the end-user (in this case, older adults) experience and expertise with technology is considered when designing technologybased interventions and other technologies.

Factors such as reduced eyesight, hearing impairment, and mobility issues all might impede technology use for older adults. These factors should be considered and accounted for so that the older adult population is accommodated.

Digital peer support, when people are available to assist with technology problems, can also play a critical role in expanding access to communication technology.

COVID-19 lockdowns posed serious barriers to physical activity for older adults because in many cases those activities are carried out in public spaces, such as a gym, or in social atmospheres, such as with friends.19 Older adults who rely on community programs or reside in senior living facilities were heavily affected by reduced physical activity during lockdowns. Volunteering is an important opportunity for social engagement. Older adults volunteer at a higher rate than the general population, but these opportunities were reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the CASOA survey, the share of older adults in Central Indiana reporting opportunities to volunteer fell from 80 percent in 2017 to 59 percent in 2021. Paradoxically, within the same group, a greater proportion of older adults reported volunteering their time, rising from 36 percent to 50 percent.

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

n

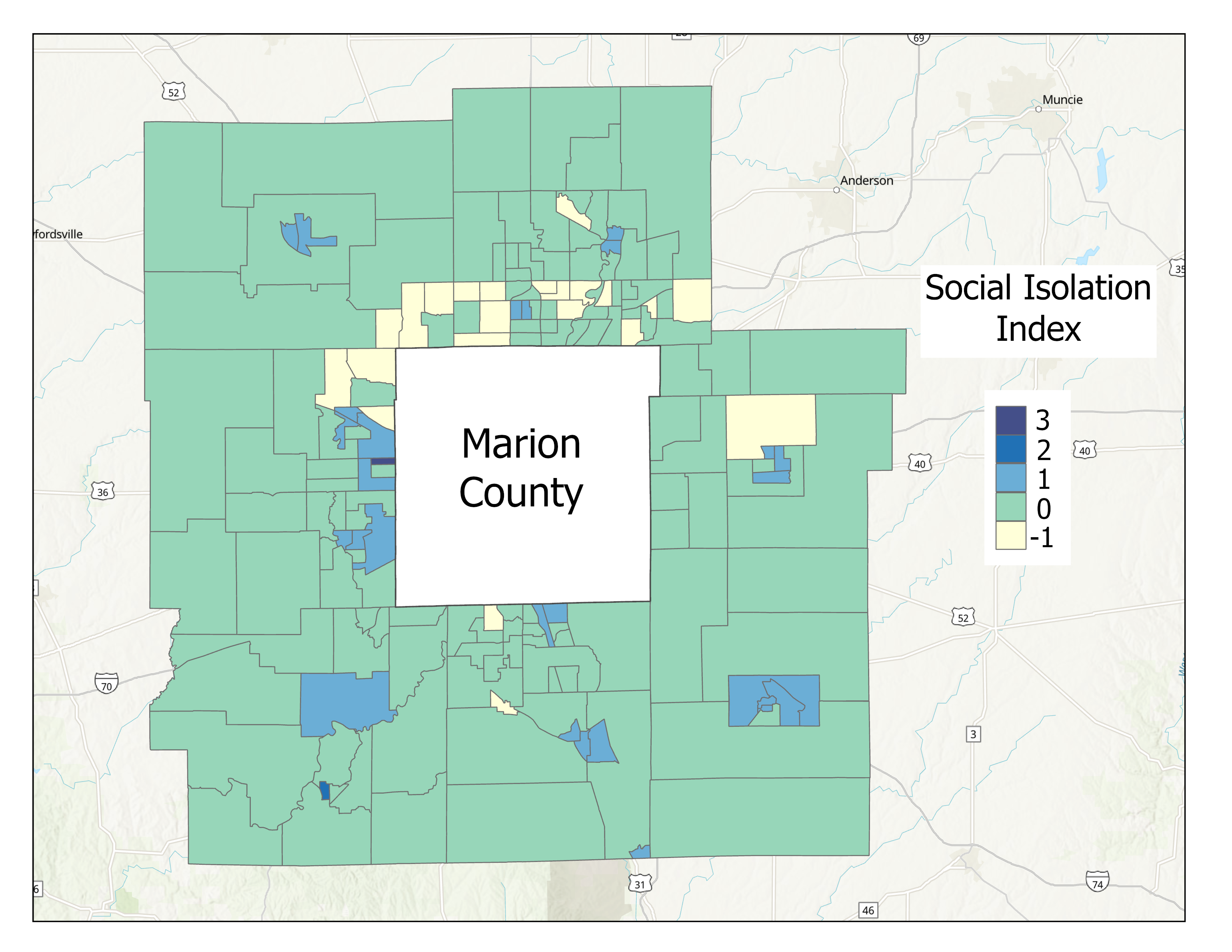

Social Isolation

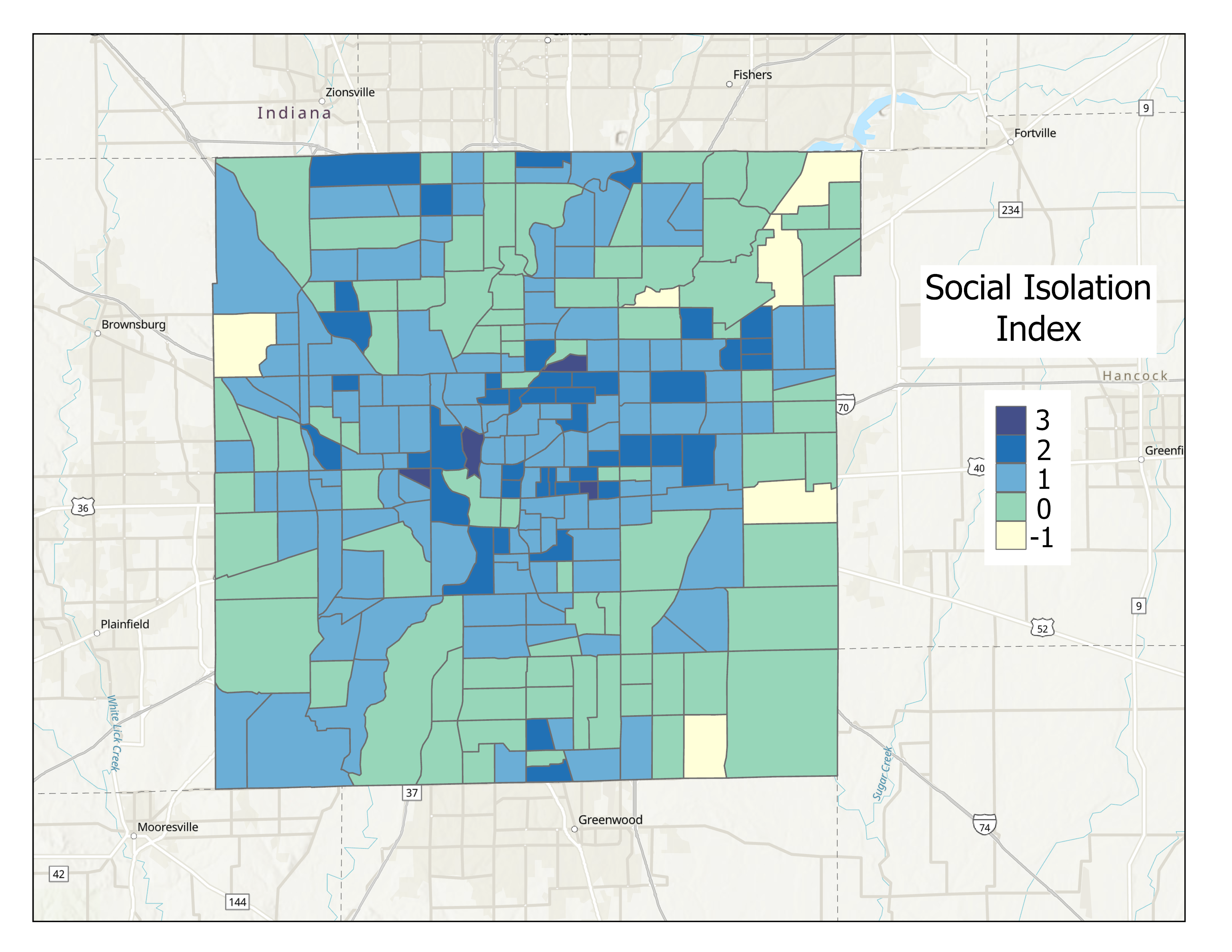

Socially isolated seniors are at heightened risk for poor health if they lack access to help when needed, from transportation for medical care to basic needs like food. In Eric Klinenberg’s study of heat-related deaths caused by the 1995 heatwave in Chicago, he found that the majority of deaths were older adults, and the majority of those experienced social isolation.20 While there is no standard aggregate measure available for social isolation, America’s Health Rankings created a measure of social isolation for older adults from survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau, combining measures of disability, marital status, living alone, and poverty.21 This approach was replicated for this report, with separate maps (shown on page 8.8) created for Marion County versus the surrounding counties, because demographically, these variables are significantly different between rural and urban areas.

Below are reports about a few populations at special risk of social isolation. These are grandparents taking care of grandchildren, LGBTQ individuals, and non-English speaking households.

Grandparents Living with and Responsible for Grandchildren

Taking care of grandchildren provides meaning in many older adults’ lives. However, it can also be a risk for social isolation, as described below. In Central Indiana, there are over 17,000 households where grandparents are living with their grandchildren (5.3 percent of households). There is a greater poverty rate among older adults with these kinds of multigenerational families than those without. The racial and ethnic composition of many of these households is similar (Latinx, White, and other), although Black families are significantly more likely to be living in these multigenerational households. In households where older grandparents are living with grandchildren, 37 percent have direct responsibility for those grandchildren.

A review of national data found that the number of grandparents raising their grandchildren has risen significantly since 2010. Several reasons for this trend are mentioned, such as parental “substance abuse, child abuse and neglect, intimate partner violence, and parental incarceration”.22 These grandparents often feel socially isolated from their peers and have less time to spend with their intimate partners, though the presence of social support systems mitigated these effects. Further, the review found that these families faced financial instability, as well as negative physical and mental health outcomes. However, interventions can help develop coping mechanisms to build grandparent resiliency, decreasing these negative outcomes.23

LGBTQ+ Older Adults

While state counts of members of the LGBTQ+ community are difficult to obtain, there are an estimated 229,000 LGBTQ+ people in Indiana (those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender) and eight percent of those are older adults (approximately 18,320 who are age 65 and older).24

About 0.3 percent of those 65 and older identify as transgender. According to a 2020 study, there are no state laws in Indiana protecting the LGBTQ+ populations in the categories of employment, education, public accommodations, housing, or credit. This puts all members of LGBTQ+ communities, including older adults, at greater risk, as they often fear they must hide their sex or gender status to prevent discrimination.25 At the national level, this is particularly true of transgender and nonbinary older adults, who, for example, reported more than double the rate of rental discrimination than gay men (46 percent versus 20 percent), with lesbian women also reporting high rates of rental discrimination (34 percent).26

The American Psychological Association reports that “Generational differences and lack of legal protection may cause older LGBTQ+ adults to be less open about their sexuality. Social isolation is also a concern because LGBTQ+ older adults are more likely to live alone, more likely to be single, and less likely to have children than their heterosexual counterparts”.27 According to a 2022 national study by AARP, older gay men are half as likely as lesbians to have children (11 percent vs 20 percent), as well as significantly more likely to live alone (40 percent vs 28 percent), putting them at higher risk of social isolation.28

n

Non-English-Speaking Households

English is not the primary language in about 10 percent of Central Indiana households (ACS 2021, 5-year). Spanish is the primary language for five percent of households and some other language is the primary language for six percent of households. Households where Spanish is the primary language have a higher chance of experiencing poverty than English-speaking households or some other language. Ponce et al (2006) found that older adults with limited English proficiency were four times more likely to report feeling sad all or most of the time.29 The Urban Institute (2018) found that limited English proficiency is the dominant predictor of low rates of homeownership, even when controlling for other factors.30

Older adults experiencing poverty are more likely to be socially isolated

Studies have shown that low-income older adults are less likely to have robust social networks and are more likely to be socially isolated than those with a higher socioeconomic status.31 Below are factors that can contribute to this disparity in social isolation for older adults experiencing poverty:

Individual factors

Poorer health:

Older adults with low incomes have greater physical decline and poorer psychological well-being than those with higher incomes.32 Due to their economic constraints, these individuals are less likely to be insured, able to afford prescriptions, or access to healthcare.33 These challenges caused by poorer health can leave older adults more likely to be socially isolated.34 35 Black older adults may experience these barriers more acutely than their White peers—one study found that Black older adultswere 70 percent less likely to rate their physical health as ‘good’ compared to White older adults, even after controlling for other possible causes.36 This social isolation can in turn exacerbate the very health issues that may have contributed to isolation in the first place.37

Fear of crime:

Individuals living in low-income households are more likely to be impacted by crimes than their higher-income peers. 38 Distrust and fear of crime can lead older adults in low-income neighborhoods to avoid social contact outside family or close friends. This often means less engagement in social activities and fewer people in their social networks.39 Focus groups conducted with older adults in Central Indiana revealed that this was much more of a concern in rural than in urban settings. However, older adults in urban areas were more afraid of being scammed over the phone than of crime in their neighborhoods. See the Community Perspective discussion found later in this section.

Interpersonal factors: Less likely to be married

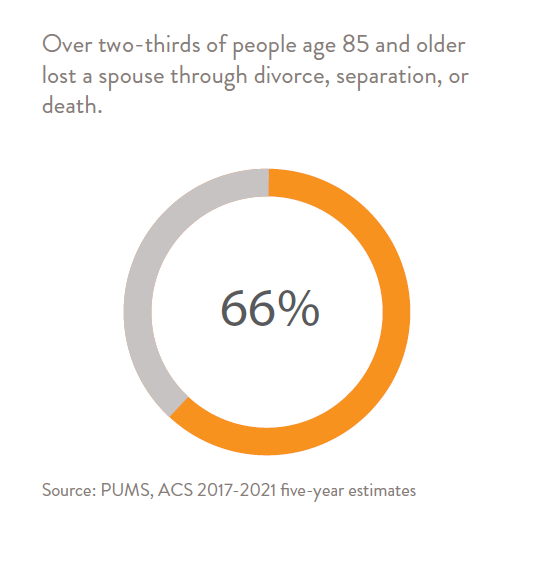

Nearly 70 percent of older adults experiencing poverty are unmarried, meaning they are widowed, divorced, or never married.40 Roughly half of unmarried older adults report loneliness, which is a higher rate than their married counterparts.41 Black older adults may be at even greater risk for loneliness, as they are less likely to be married/ partnered than their White and Latinx peers.42

Community factors: fewer organizations and resources in low-income communities

Many high-poverty neighborhoods have fewer community institutions such as churches, social clubs, and community organizations compared to high-income neighborhoods. This results in fewer opportunities for older adults to be involved in the community or expand their social networks.43

Community Perspective

Findings from Key Informant Interviews

Key informants for this report included those involved in senior care services or administration in Central Indiana.44 Isolation is considered by the informants to be harmful to older adults due to unattended health concerns, not eating properly, and low family contact. One informant noted that many of the individuals who seek out organizations are those without spouses who are looking for friendship and socialization.

Informants were not sure how to find or reach shut-ins—very isolated individuals—if they are not requesting services. In some cases, a professional caregiver will refer an older adult to a social service program. One informant mentioned that if they can get an older, isolated individual to their facility, they can usually get that individual to keep coming back, because they offer friendship, as well as resources, such as transportation and meals.

Older adults with resources have more options for social inclusion, including senior centers, games, book clubs, dancing clubs, and other activities.

In addition to physical resources, these activities require some mobility independence, transportation, social skills, and motivation sufficient to overcome uncertainty. Any of these can be a barrier even for older adults with financial means, and CASOA data show that few (14 percent) engage in such activities, even specifically older adult activities (e.g., senior centers).

Informants mentioned purposeful living activities, such as spirituality, church, and time with friends. Games, hobbies, and day trips were also mentioned, but in the context of spending time socializing with friendly others.

Findings from Focus Groups with Older Adults

Focus groups with older adults were conducted across Central Indiana. Some focus group participants expressed fear of becoming isolated. To counter this, some seek socialization through group involvement at churches or senior centers or engage in volunteerism. Activities are discovered through church, newspaper, mail flyers, bulletin boards at centers (e.g., YMCA), or libraries. Few expressed use of internet or social media to find activities. Some had smartphones, used mostly for calling and texting, rather than information look-up.

Circumstances that limit socialization include lack of family or family who do not come to visit, limited mobility, lack of transportation, the combination of limited mobility and lack of public transportation and limited financial resources for activities.

Purposeful living seemed to involve time with others including time with grandchildren and family, caregiving of spouse or others, volunteering and participating in church. A few individuals in the focus groups expressed enjoying activities on their own such as shopping, cooking or watching television.

Like key informants, several focus group participants expressed concern that there are many older adults who are isolated either by choice or circumstance and that it is difficult to reach these people or get information to them.45

What is Available or Being Done?

Interventions in Central Indiana to address social exclusion in older adults include several efforts. First, churches and families provide social inclusion opportunities for older adults in roles such as caregiver, sitter, and volunteer. Volunteer opportunities may be diverse within these institutions. Second, Senior Companions, which is a service that matches trained volunteers with older adults needing companionship, is reaching some isolated older adults living in Marion County. Third, senior centers and organizations offer social activities, as discussed above, including dancing, exercises, book clubs, and meals together. Even home-delivered meals, which provide social interaction, are not the same as social inclusion.

“One of the best sellers for meals program is that it was an interruption to a lonely life and human contact.”

– Key Informant

What are Ideas for Solutions?

One key informant described an idea for a program that is much like what Senior Companions now provides.

“It has been a thought to harness a group of volunteers or nursing students or a person with common sense to go into homes with high-risk people, check in with them and companionship support. These programs have been successful in other areas. It is a barrier to think a professional has to do this work. Nursing students would be great because they could perform blood pressure checks, weight checks, etc.”

– Key Informant

An interesting observation from Senior Companions is that the volunteers often seem to get more social satisfaction from the program than do the older adults needing companionship, which points to increased opportunities for older adults to volunteer as a path to interventions for wellbeing. Work by Johns Hopkins faculty in the Baltimore Experience Corps trial, which paired older adults with elementary school volunteers, showed increased physical, social, and cognitive activity engagement, and even slowed brain atrophy.46 Importantly, this trial involved older adults like the Indy Senior Companion participants— predominantly Black women with one to two years of post-high school education. The Experience Corps program is now supported by the AARP Foundation in 22 cities, including Evansville, Indiana, but not Indianapolis.

One informant felt strongly that services are not well coordinated or communicated to older adults and their families, and that better efforts in this area would match older adults to services and opportunities they need.

Bridging and Linking Social Capital

Social capital is a way of talking about how people access a variety of resources through both formal and informal social networks.47 It is important for older adults, as social capital is connected to social, physical, and emotional wellbeing.48 Social capital resources can include opportunities for socialization and recreation; connections to paid or volunteer jobs; friendships with those who can provide informal help with small informal needs, such as a lift to the grocery or a simple car repair; informal access to people who can make a connection to formal social service organizations for health, housing, legal, or other types of needs; people who can be trusted, allowing older adults to feel safe, resulting in increased interaction with others and enjoyment of outdoor spaces.

There are several types of social capital, some core types being bridging, bonding, and linking.49 Bonding and bridging capital are ways to talk about horizontal relationships within communities, while linking capital

includes vertical connections to formal institutions, such as government, or people with higher levels of social power and resources. Bonding capital is characterized by trust between neighbors, social cohesion, collective efficacy, feelings of safety, people’s willingness to help their neighbors, and civic participation.50 Bridging capital describes relationships occurring outside of one’s immediate social network, such as connections between older adults in one community to other social networks that have resources they may need. Both bridging and bonding capital are typically informal networks within and between communities. Linking capital allows individuals access to resources available through formal networks, such as non-profits or government services.

Over time, communities can see changes in these kinds of informal networks. For example, since 2013, older adults reported decreased participation in community religious services, dropping from 67 percent to 60 percent in 2021–not a dramatic reduction, but it parallels similar changes that have occurred over the last decade in all age groups (CASOA 2013, 2017, & 2021). Religious participation is often seen as a form of bonding capital, especially in Evangelical churches. On the other hand, rates of “assisting friends, relatives or neighbors” have remained relatively stable, changing little since 2013, indicating bonding capital has remained mostly unchanged. In contrast, use of public libraries by older adults has dropped from 65 percent in 2013 to 49 percent in 2021. Because libraries can be hubs for local community networks, changes in library usage can indicate changes to bridging capital.

Older adults who are socially isolated often have deficits in all these forms of capital, since connections with other people in social networks form the core of social capital. Generally, older adults tend to have stronger bonding capital than younger adults, and people living in cities tend to have stronger bridging capital than those in rural areas. However, some communities are excluded from many types of resources, whether from a history of social discrimination, or even residential patterns formed through segregation history.51 While segregation and historical discrimination against communities can limit some individuals from accessing formal resources, these individuals can still have strong informal connections within their networks. Unfortunately, there may be limited connections to external networks with greater levels of resources—such as money for lending or professionals for legal, medical, or housing services, etc.

Each form of capital is important for communities. But while trust and cohesion, components of bonding capital, are important, and often related to reports of social well-being, there is mixed evidence that bonding capital is related to improved economic or health outcomes. Therefore, it is sometimes referred to as a ‘getting by’ measure (how well communities and their members are ‘getting by’).52 In contrast, measures of ‘getting ahead’, bridging and linking capital, have stronger evidence of being related to communities that see economic improvements and better health outcomes for members. There are no established measures for bridging or linking capital using aggregate public data (these are usually measured with surveys), but proxy measures have been cited in the literature.

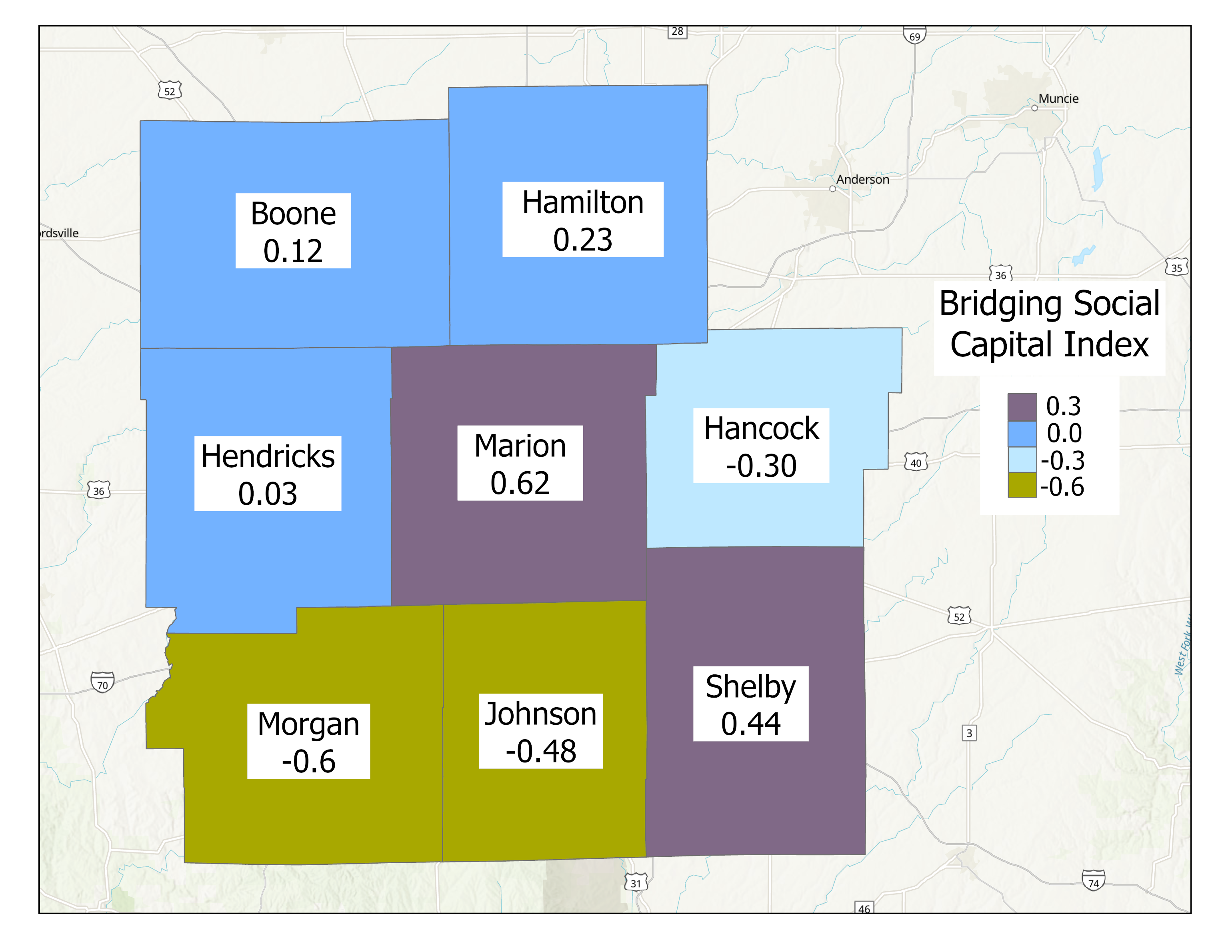

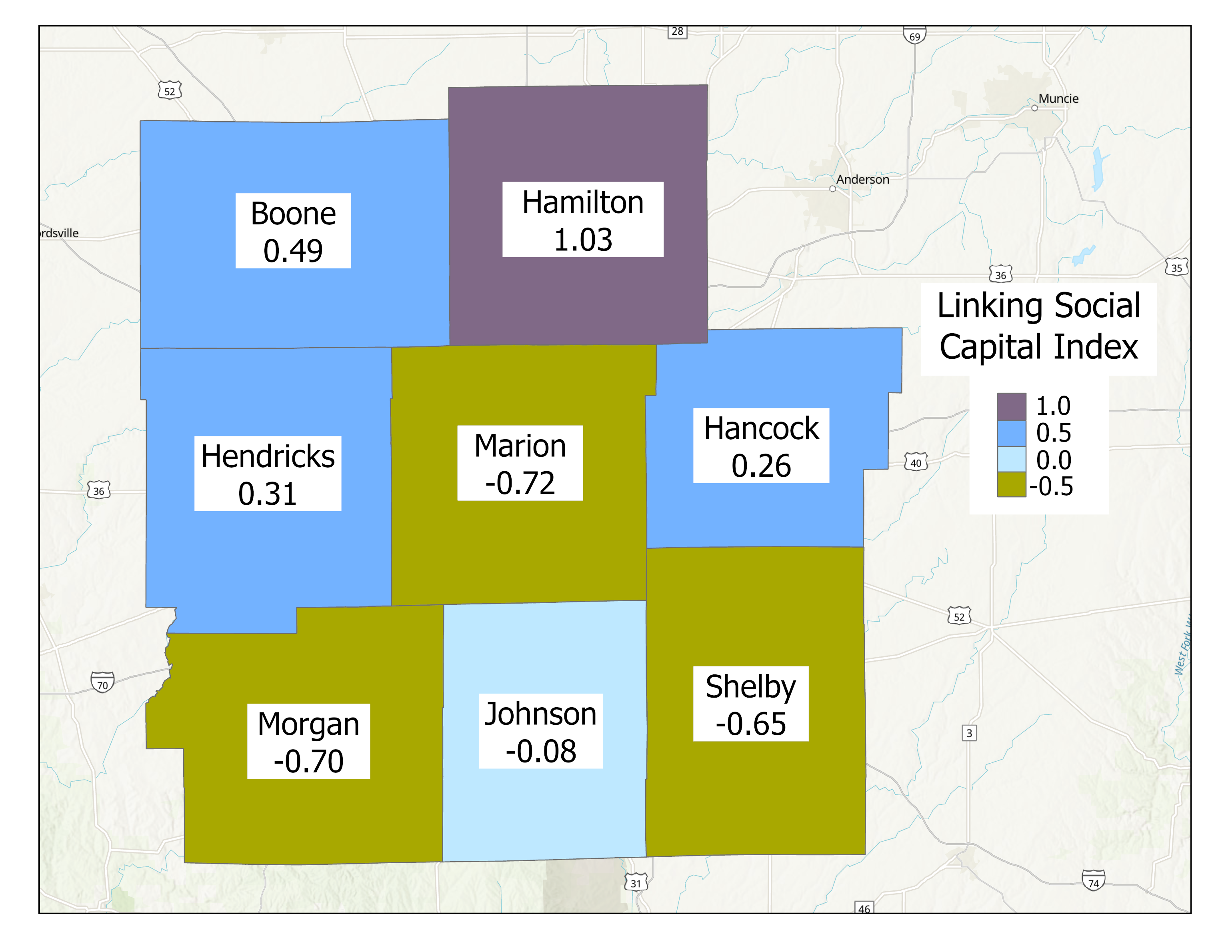

The Polis Center created an index for bridging and linking capital at the county-level for Indiana and mapped these for Central Indiana. The Bridging Social Capital Index shows that Hamilton and Marion counties have the highest scores, while Morgan County has the lowest. Higher scores imply stronger connections between communities, and an ability to share resources between these communities.53 The Linking Social Capital Index shows that Hamilton County has one of the highest levels in the state, and Marion, Shelby, and Morgan counties have the lowest levels in this region.54 A high score implies strong connections between communities and centers of authority, or access to higher-level resources.

- Frankl, Viktor Emil. Man’s Search for Meaning. Boston: Beacon Press, 2006.

- Haidt, Jonathan., and OverDrive Inc. The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

- Burgin D., O’Donovan, A., d’Huart D., et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Telomere Length a Look

Into the Heterogeneity of Findings-A Narrative Review. Front Neurosci.2019;13:490. - Levine, M.E., Crimmins, E.M. Evidence of accelerated aging among African Americans and its implications for mortality. Soc Sci Med.2014;118: 27-32

- Polis Center. Transportation | The State of Aging in Central Indiana. Accessed September 15, 2023. https://centralindiana.stateofaging.org/report-data/transportation2023/

- AshaRani P.V., Lai D., Koh J., Subramaniam M. Purpose in Life in Older Adults. Int J Env Res Pub Hlth. 2022; 19: 5860.

- Taylor, J., McFarland, M.J., Carr, D.C. Age, perceptions of mattering, and allostatic load. Journal of Aging and Health. 2019; 31(10): 1830-1849.

- Wynn, M.J., Dewitte, L., Hill, P.L. Transitions and opportunities: Considering purpose in the

context of healthy aging. In Burrow A.L., Hill P.L., The Ecology of Purposeful Living Across the Lifespan. 2020; (pp 59-72). Springer. doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52078-6_4 - AARP, NORC at the University of Chicago. Home and Community Preferences 2021. https://

www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/liv-com/2021/2021-home-community-preferences-annotated-questionnaire-age.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00479.002.pdf - Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults TM. National Research Center Inc., 2021.https://cicoa.org/news-events/research/

- Coleman, M.E., Manchella, M.K., Roth, A.R., Peng, S., and Perry, B.L. What kinds of social networks protect older adults’ health during a pandemic? Social Networks. 2022; 70: 393-402.

- Krendl, A.C., Perry, B.L.. The Impact of Sheltering in Place During the COVID-19 Pandemic on

Older Adults’ Social and Mental Well-Being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci. 2021; 76(2): e53-e58. - Seibert, T., Schroeder, M.W., Perkins, A.J., et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the

Mental Health of Older Primary Care Patients and Their Family Members. Journal of Aging Research, 2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/6909413 - Krendl, A.C., Perry, B.L.. The Impact of Sheltering in Place During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Older Adults’ Social and Mental Well-Being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci. 2021; 76(2): e53-e58.

- Giroux, S., Waldman, K., Burris, M., et al. (2022) Food security and well-being among older, rural Americans before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Plos One 17(9): e0274020

- Hodges, M., Butler, D., Spaulding, A., Litzelman, D.K. (2023). The Role of Community Health-Workers in the Health and Well-Being of Vulnerable Older Adults during the COVID Pandemic.Int J Env Res Pub Hlth 20 (4): 2766-2778.

- Coleman, M.E., Manchella, M.K., Roth, A.R., Peng, S., and Perry, B.L. What kinds of social networks

protect older adults’ health during a pandemic? Social Networks. 2022; 70: 393-402. - Cosco, T.D., Fortuna, K., Wister, A., Riadi, I., Wagner, K., and Sixsmith A. “COVID-19, Social Isolation, and Mental Health Among Older Adults: A Digital Catch-22.”J Med Internet Res. 2021; 23(5): e21864. https://doi. org/10.2196/21864

- Son, J., Nimrod, G., West, S., Janke, M., Liechty, T., and Naar, J. “Promoting Older Adults’ Physical Activity and Social Well-Being during COVID-19.” Leisure Sciences. 2021; 43(1-2): 287-294. 10.1080/01490400.2020.1774015

- Klinenberg, E. Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago. 2002; University of Chicago Press.

- America’s Health Rankings. Risk of Social Isolation – Ages 65+. https://www.americashealthrankings.

org/explore/senior/measure/isolationrisk_sr/state/ALL - Choi, M., Sprang, G., Eslinger, J. Grandparents raising grandchildren. Family and Community Health. 2016; 39: 120-128.

- Hayslip, B., Fruhauf, C, Dolbin-MacNab, M. Grandparents raising grandchildren. The Gerontologist.2016; 59: e152-63)

- Williams Institute, LGBT People in the US Not Protected by State Non-Discrimination Statutes.https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-ND-Protections-Update- Apr-2020.pdf

- Caceres, B., Travers, J., Primiano, J., Luscombe, R., Dorsen, C. Provider and LGBT individuals’ perspectives on LGBT issues on long-term care: A systematic review. The Gerontologist. 2020; 60: e169-183.

- Cantave, C. “Dignity 2022: The Experience of LGBTQ Older Adults” AARP Research. 2022 https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/life-leisure/2022/lgbtq-community-dignity-2022-report.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00549.001.pdf

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Aging. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pi/lgbt/resources/aging

- Cantave, C. “Dignity 2022: The Experience of LGBTQ Older Adults” AARP Research. 2022 https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/life-leisure/2022/lgbtq-community-dignity-2022-report.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00549.001.pdf

- Ponce, N.A., Hays, R.D., Cunningham, W.E. Linguistic disparities in health care access and health

status among older adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006; 21, 786–791. - Golding, R., Goodman, L., Strochak, S. Is limited English proficiency a barrier to home- ownership? Urban Institute.2018 https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/97436/is_limited_english_proficiency_a_barrier_to_homeownership_0.pdf

- America’s Health Rankings. “Explore Risk of Social Isolation – Ages 65+ in the United States | 2020 Senior Health.” Accessed January 21, 2021. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/senior/measure/isolationrisk_sr/state/ALL.

- Arendt, J.N. (2005). “Income and ‘Outcomes’ for Elderly: DO the Poor Have A Poorer Life?” Social Indicators Research 70: 327–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-1545-8.

- Wedmedyk, S. (2015). “Older Adults in Poverty Face Compounded Health Inequities.” Association of State and Territorial Health Officials. https://www.astho.org/StatePublicHealth/Older-Adults-in-Poverty-Face-Compounded-Health-Inequities/8-25-15/.

- Snedeker, Lauren. (2017). “Aging & Isolation — Causes and Impacts.” Social Work Today. https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/011917p24.shtml.

- Wedmedyk. (2015).

- Miyawaki, C. (2015). “Association of Social Isolation and Health across Different Racial and Ethnic Groups of Older Americans.” Ageing and Society 35: 2201–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X14000890.

- Perissinotto, C.M., Irena S.C., Covinsky, K. (2012). “Loneliness in Older Persons: A Predictor of Functional Decline and Death.” Archives of Internal Medicine 172: 1078–83. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.1993.

- Harris, B.H. Harris and Kearney, M.S. (2014). “The Unequal Burden of Crime and Incarceration on America’s Poor.” Brookings (blog). https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2014/04/28/the-unequal-burden-of-crime-and-incarceration-on-americas-poor/.

- Rankin, B.H., Quane, J. (2000). “Neighborhood Poverty and the Social Isolation of Inner-City African American Families.” Social Forces 79: 139–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/2675567.

- U.S. Social Security Administration. “Population Profile: Marital Status and Poverty.” Accessed January 21, 2021. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/population-profiles/marital-status-poverty.html.

- Thayer, C., Anderson, O. (2018). “Loneliness and Social Connections: A National Survey of Adults 45 and Older.” AARP Research. https://doi.org/10.26419/res.00246.001.

- Miyawaki, C. (2015). “Association of Social Isolation and Health across Different Racial and Ethnic Groups of Older Americans.” Ageing and Society 35: 2201–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X14000890.

- Snedeker, Lauren. (2017). “Aging & Isolation — Causes and Impacts.” Social Work Today. https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/011917p24.shtml.

- Thirty-five key informant interviews with caregivers and service providers were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. Public and not-for-profit sector leaders and service providers who are knowledgeable about service systems and issues pertaining to older adults in Central Indiana were identified and interviewed as key informants during report preparation.

- It is important to note that people who participate in focus groups, such as the ones conducted for this report, often seek socialization and have the resources to participate. Some participants noted they were participating in the focus group for the socialization. The needs and concerns of more isolated older adults may differ from those of the focus group participants.

- Carlson, M.C., Kuo, J.H., Chuang, Y.F.,Varma, V., Harris, G., Albert, M., Erickson, K., Kramer, A., Parisi, J., Xue, Q., Tan, E., Tanner, E., Gross, A., Seeman, T., Gruenewald, T., McGill, S., Rebok, G., Fried, L. (2015). Impact of the Baltimore Experience Corps Trial on cortical and hippocampal volumes. Alzheimer’s Dement.11(11):1340-1348.

- Poder, T. (2011). What is really social capital? A critical review. The American Sociologist 42: 341-367.

- Browne-Yung, K., Ziersch, A., Baum, F. 2013. ‘Faking til you make it’: Social capital accumulation of individuals on low incomes living in contrasting neighborhoods and its implications for health and wellbeing. Social Science & Medicine 85: 9-17. Buck-McFadyen, E, Akhtar-Danesh, N., Isaacs, S., Leipert, B., Strachan, P., Valaitis, R. (2019). Social capital and self-rated health. Health and Social Care in the Community 27: 424-436. Carpiano, R. 2006. Neighborhood social capital and adult health: An empirical test of a Bourdieu-based model. Health and Place 13: 639-655. Pinxten, W., Lievens, J. (2014). The importance of economic, social and cultural capital in understanding health inequalities. Sociology of Health& Illness 36: 1095-1110. Smiley, K. 2020. Social capital and industrial air pollution in metropolitan America. Sociological Quarterly doi=10.1080/00380253.2019.1711252 (pre-print publication online). Villalonga-Olives, E., Almansa, J., Knott, C., Ransome, Y. (2020). Social capital and health status: Longitudinal race and ethnicity differences in older adults from 2006-2014. International Journal of Public Health 65: 291-302.

- Osborne, C., Baldwin, C., Thomsen, D. 2016. Contributions of social capital to best practice urban planning outcomes. Urban Policy and Research 34: 212-224.

- Kim, H.Y. (2018). Effects of social capital on collective action for community development. Social Behavior and Personality 46: 1011-1028. Pabayo, R., Grinshteyn, E., Avila, O.; Azrael, D., Molnar. (2020). Relation between neighborhood socio-economic characteristics and social cohesion, social control, and collective efficacy. SSM-Population Health 10: 1-8.

- Daly, M., Silver, H. (2008). Social exclusion and social capital. Theory and Society 37: 537-566.

- Lukasiewicz, K., Bahar, O., Ali, S., et al. (2019). Getting by in New York City: Bonding, bridging and linking capital in poverty-impacted neighborhoods. City and Community 18: 280-301.

- The Bridging Social Capital Index is composed of 4 measures: per capita employees of non-religious organizations that facilitate civil participation (NAICS 813, minus religious organizations), segregation (Black-White dissimilarity index), income inequality, and per capita mainline Protestants & Catholics. These two religious groups are cited as being more prone to work with secular community organizations, generating bridging capital, while Evangelicals are more likely to invest deeply in their own congregation, generating bonding capital. Beyerlein, K., Hipp, J. (2005). Social capital, too much of a good thing? Social Forces 84: 995-1013. Clark, J., Stroope, S. (2018). Intergenerational social mobility and religious ecology. Social Science Research 70: 242-253. Nisanci, Z. (2017). Close social ties, socioeconomic diversity, and social capital in US congregations. Review of Religious Research 59: 419-439. Wuthnow, R. (2002). Religious involvement and status-bridging social capital. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 669-684.

- The Linking Social Capital Index is composed of 4 measures: Voter turnout (2016-2018 average), Census response rates (2010), per capita employees at establishments that provide services to the elderly & disabled (NAICS 624120), and per capita service professionals (legal, healthcare, education, public administration).