Financial Stability

Persona

Patricia

68 years old

Works at local library branch

Retired office manager

Patricia is a single, 68-year-old Latina woman living on the west side of Indianapolis. The majority of her income comes from Social Security benefits, which she supplements with part-time work as a checkout assistant at a neighborhood library—a job she found after retiring from her position as the office manager at her church two years ago. Her total annual income is $31,000. Her rent is $800 a month for the apartment that she moved into after her husband of 40 years died several years ago—which means that housing costs consume about 31 percent of her income (or slightly more than the recommended limit of 30 percent). Patricia has about $75,000 in retirement savings, and her car is 10-years old. The car is paid off, but increasingly frequent and unpredictable repair costs are a financial burden and a significant source of stress. Selling it, however, would mean relying on public transit, rides from friends, and walking.

In addition to housing, transportation, and food, Patricia’s major expenses include utilities, clothing, and household upkeep. She also believes in tithing (i.e., giving a percentage of her income) to her church. She is in relatively good health and receives Medicare benefits, but she covers some of the cost of the prescription drug she takes for high blood pressure. Although Patricia’s income is more than $4,000 above the ALICE “survival budget” of $26,700—i.e., the estimated income needed to meet basic needs for a person in her demographic group—she struggles to make ends meet and feels the pinch especially during the holiday season. She likes to splurge on gifts for her children and grandchildren at Christmas. But two new tires for her car depleted all the money she had budgeted for gifts last year, which forced her to reduce her spending and dip into savings. Given her relatively low retirement nest egg—and the fact that she usually has little to no money left over to add to it—she worries about how she will make ends meet if her car repair, healthcare, and other costs increase. An added worry is that her current spending levels depend on her part-time job as a library assistant. If and when she can no longer earn that supplemental income, it will likely mean significant lifestyle adjustments—giving up her car, most likely, as well as finding lower-cost housing.

Financial stability is crucial for older adults to maintain a decent quality of life, age in place, and access critical resources. Whether or not an older adult is financially stable is influenced by life experiences and other characteristics. This section of the report assesses financial stability, including poverty levels, household income, basic living expenses, and the financial experiences of older adults in Central Indiana.

- All three older adult age groups experienced significant increases in income between 2015 and 2020.

- Overall, one in 12 older adults experiences poverty, with poverty rates similar between older adults in Central Indiana and Indiana as a whole.

- Black and Latinx older adults are more likely to experience poverty than White older adults, and older women are more likely to experience poverty than older men.

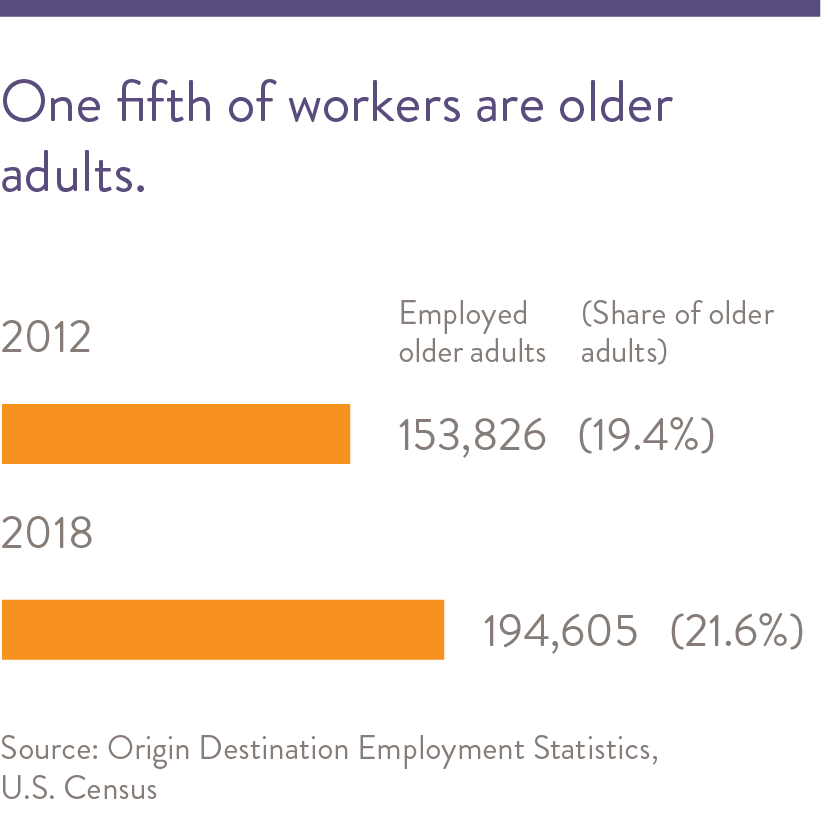

- Nearly one fifth of adults of traditional retirement age continue to work outside the home.

- Older adults face barriers to attaining and maintaining a job, such as the ability to effectively use technology.

- Healthcare and housing are the costliest expenses for older adults in Central Indiana.

- Over two in five older adults reported recently experiencing at least some difficulty affording daily expenses or finding affordable health insurance.

- In general, Central Indiana is similar to Indiana as a whole in many measures of financial stability, but there are some notable differences, such as a greater percent of older adults in Central Indiana paying over 30 percent of their income on housing costs.

- Among older adults (age 55+) in Central Indiana, as age increases, income generally decreases.

Income typically decreases as households age

2020 median household incomes in Central Indiana

Income has increased across all older adult age groups in Central Indiana since 2015

The latest income data we have is from surveys taken between 2016 and 2020, well before inflation reached high levels. We will have to wait until the end of 2023 to see this data about 2022.

MEDIAN HOUSEHOLD INCOME AND POVERTY

Household income includes sources such as wages from employment, retirement income, Social Security income Supplemental Security Income, and other public assistance payments.1 2Among older adults in Central Indiana, median household income varies by age group – as age increases, income generally decreases. In 2020, the median household income of younger-old adults was $72,100.3 Upon approximate retirement age, that income declines to $51,300 for the middle-old. A further decrease occurs when the older adult population reaches age 85 and older, when median household income declines to $35,800.4 5

Overall, between 2015 and 2020, the median household income of older adults (age 55+) in Central Indiana increased, from about $47,000 to $57,000. All three age groups experienced significant gains in median household income between 2015 and 2020. However, not all populations were equally impacted by these gains. For example, while White older adult households achieved significant increases in median income from 2015-2020, the income gains experienced in Black and Latinx households were not statistically significant. 6 Thus, while Black and Latinx older adults had greater median incomes in 2020, it is difficult to discern how real the actual increases in income were.

Poverty and financial insecurity are a challenge for older adults on a fixed income. According to the U.S. Census official poverty measure, Central Indiana has lower poverty among older adults than both Indiana and the nation. According to 2021 estimates from the American Community Survey, the poverty rate is about eight percent for people age 55 and older. This is similar to working age adults, but lower than young adults and children.

However, the official poverty measure has underestimated poverty among older adults in recent years. Additionally, it does not consider public assistance programs that are not accessible to all Americans, e.g., younger-old adults have fewer resources available to them until they are eligible for benefits like Medicare and in most cases, social security.7 The supplemental poverty measure has been consistently higher than the official poverty measure for older adults (age 65 and older) across the U.S. 8 Until 2020, there was almost a four point gap between the supplemental and official poverty measures. In 2020 and 2021, that difference shrank to less than one percentage point, due in part to federally-enacted pandemic relief policies.

Specifically, nationwide, the supplemental poverty rate fell significantly for all ages in 2020. Households were supported by cash assistance during the pandemic, and this reduced poverty levels. In 2021, the expanded Child Tax Credit in the American Recovery Plan Act reduced child poverty by about half. Working age adults also benefitted from the Child Tax Credit payments. The poverty rate among older adults rose, however, as their pandemic benefits expired. Still, poverty levels were lower for older adults in 2021 compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Official poverty rates tend to be higher for younger people

Official poverty measure, Central Indiana, 2021 estimate

Focus groups of older adults reported experiencing poverty throughout their lives and continuing to lack financial stability, despite years of employment.9

Key informant service providers discussed difficulty and low success rates employing those who continue to experience poverty.10 This suggests that if poverty rates are high among younger-old adults while many are still employed, they may not be able to improve their incomes when or if they retire.

In Central Indiana, according to the official poverty measure, gender disparities also exist among older adults experiencing poverty. Older women (age 55+) experienced higher poverty rates than older men in 2020, at 8.8 percent versus 7.4 percent, respectively. 11 This disparity exists throughout Indiana as well, where the poverty rate is 9.4 percent for older women and 7.4 percent for older men.

There also are stark racial disproportionalities among older adults experiencing poverty. According to the official poverty measure, between 2016 and 2020, the poverty rate among all older adults (age 55+) in Central Indiana was 8.2 percent.12 However, Black older adults (18.3 percent) and Latinx older adults (14.3 percent) experienced significantly greater poverty rates than White older adults (6.4 percent). These trends were persistent across all of Indiana as well, with Hispanic older adults experiencing a greater estimated poverty rate in Central Indiana than Indiana, but within margin of error of the estimation. Additionally, Black and Latinx older adults are more likely to be housing-cost burdened than White older adults, although the gap is much narrower between Latinx and White older adults, within margin of error. These trends also hold true throughout Indiana as a whole. Households are housing-cost burdened when they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing-related costs.13 For more on housing and housing costs, please see the Housing section of this report.

To learn more about some of the factors that influence higher poverty rates among Black older adults, please read “Highlighting Equity” below.

Poverty in Central Indiana older adults is similar to that in Indiana, and has changed little since 2015—largely within margin of error.

Supplemental Poverty in older adults is greater than the official poverty measure.

Nationally, supplementary poverty rates increased among people age 65+ between 2020 and 2021.

Poverty rate is 12% higher among the Black older adult population in Central Indiana, and 11% higher than the Black older adult population in Indiana.

Two in five Black households spend 30% or more on housing costs, nearly double that of White households.

Disparities in Incomes and Wealth

Organizational factors

Black workers are paid less than their White counterparts

The 2021 American Community Survey (one-year average) found that Black workers in Indiana earned 69 cents for every dollar earned by White workers in the state.14 Additionally, a national sample of 1.8 million employees between 2017 and 2019 found that Black workers continue to have lower earnings than White workers even when possessing the same level of education and experience.15 Because of this disparity in pay and discretionary income, it is more difficult for Black adults to save and accumulate wealth over their lifetimes.16

Social Security benefit amounts are lower for Black Americans due to lower lifetime earnings

Social Security benefits are based on income, and because Black workers earn less than their White counterparts, Black older adults tend to receive less income through Social Security when they reach retirement age.17 Social Security is the only source of income for roughly one third of American Black older adults, compared to 18% of White older adults.18

Community factors: Black adults are less likely to own their homes

In the United States, homeownership is an important avenue for building wealth.19 However, in response to the Federal Home Loan Bank Board in the 1930s, mortgage lenders and banks started to deny access to credit to purchase a house in majority-Black and low-income immigrant neighborhoods, as these areas were deemed to be “Hazardous“ for investment processes.20 As a result of these practices and other financial inequalities, Black adults are 40 percent less likely to own their own homes, and thus have less equity and wealth to pass on to their heirs.21 In 2019, the median net worth of a U.S. White family with a head of household age 55 and older was $315,000, nearly six times greater than that of the median Black family in the same age group ($53,800).22

Policy factors: Federal policies limited Black workers’ opportunities

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 allowed the federal government to endorse union groups that excluded Black workers from membership. This policy affected the ability of Black workers to obtain blue-collar jobs, further exacerbating the income and wealth gap.23

Income Sources

Employment

Employment opportunities are crucial to the financial stability of many older adults—19 percent of adults in Central Indiana participate in the labor force beyond the traditional retirement age of 65.24Adults age 55 and older make up 21.6 percent of the total workforce in the area, an increase of 2.2 percentage points since 2012. 25

Although Marion County has the largest number of working older adults in Central Indiana (95,000), it has the lowest proportion of its older adult population in its work force (21%). Conversely, Shelby County is home to the fewest working adults (5,600), but at 25 percent, has the greatest proportion of older adults in the working population.

According to focus group participants, while some older adults continue to work after retirement because they need the income, some continue to work because they enjoy their jobs or do not know what they would do after retirement. Others maintain employment because of the benefits, including health insurance coverage. Private health insurance enables access to health care providers who do not accept Medicare.

At nearly three-quarters, Marion County has the greatest proportion of older adults who work in the same county where they live, while less than one quarter of older adults who live in Morgan County also work there. 26

Social Security and Supplemental Security Income

Many older adults of retirement age depend on social security benefits when they are no longer working or are earning limited amounts. In 2020, 52 percent of older adults (age 55+) in Central Indiana received social security benefits, four percentage points fewer than the state of Indiana as a whole. 27 Among the younger-old in Central Indiana, 15% are receiving social security benefits; this number increases to 86 percent for the middle-old, and 92 percent for the oldest-old.

Adults age 65 and older or have a disability and especially limited incomes may be eligible to receive an additional federal benefit – Supplemental Security Income (SSI) cash benefits to assist them with affording their basic needs. 28 In 2020, 3.8 percent of older adults in Central Indiana received SSI benefits in comparison to 4.1 percent statewide. 29 The proportion of younger-old who receive SSI (4.3 percent) in Central Indiana is slightly higher than the middle-old and the oldest-old (3.3 percent and 3.2 percent, respectively). Once older adults begin receiving social security benefits, a portion of the value of these benefits are subtracted from the standard monthly SSI payment of $841 per individual and $1,261 per couple in 2022, which has the effect of eliminating the SSI benefits for some retirement-age adults. 30

The percentage of the population in Central Indiana receiving social security benefits is similar to Indiana as a whole, with some subtle differences in several age groups

Navigating Poverty and Financial Instability

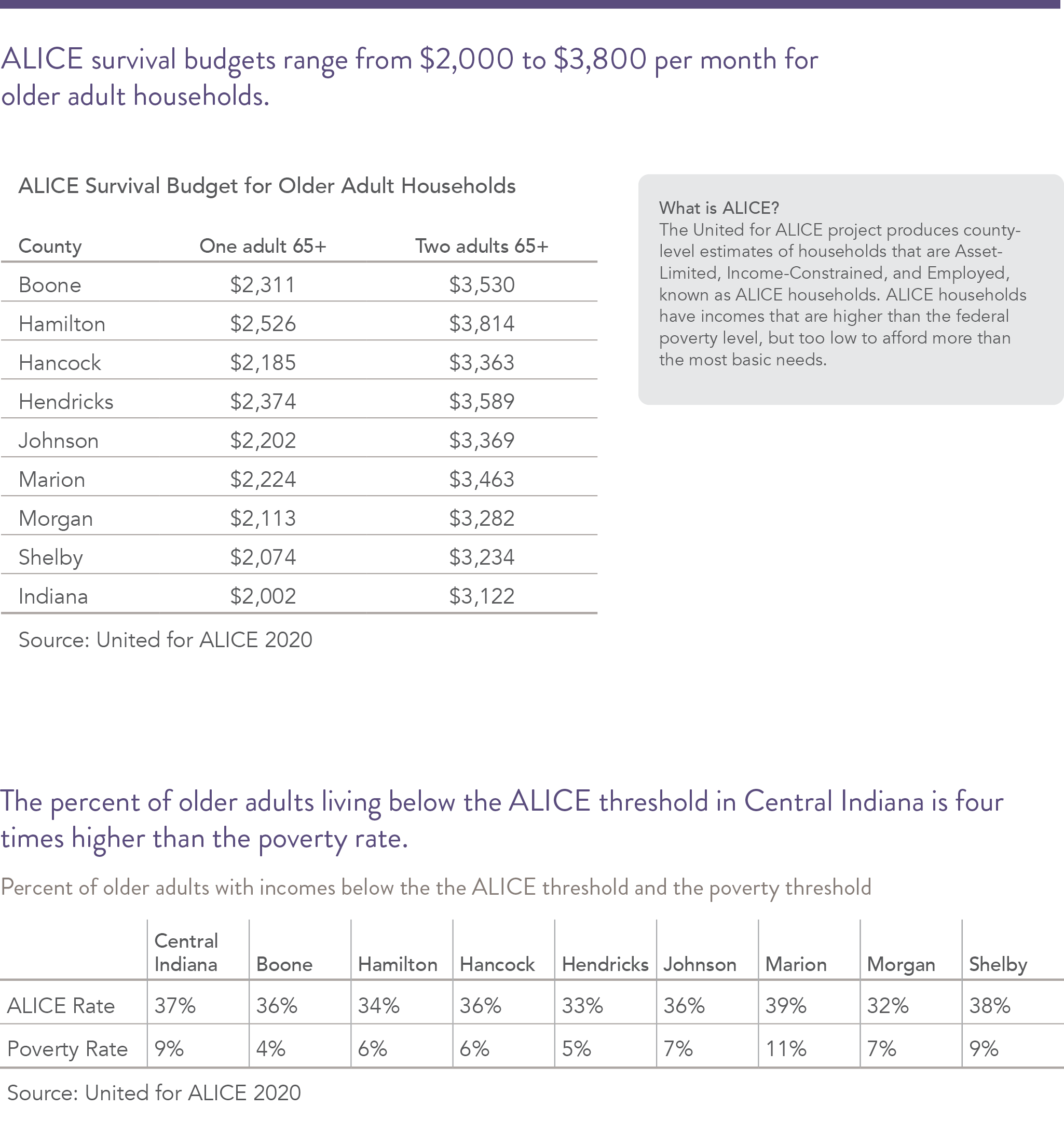

Insufficient income and poverty are not the only concerns facing older adults in Central Indiana. Managing income considering household and other important expenses is also important. The United for ALICE project produces county-level estimates of households that are Asset-Limited, Income-Constrained, and Employed, known as ALICE households. ALICE households have incomes that are higher than the federal poverty level, but too low to afford more than the most basic needs. In Central Indiana, there are an estimated 13,000 adults (nine percent) age 65 and older who experience poverty, and more than 55,000 (37 percent) whose incomes fall below the ALICE threshold.31

The “survival” or most basic budget of an older adult ALICE household depends on whether it is a household consisting of an older adult living alone or two older adults (both without children). In both cases, the budget is based upon county-specific expenses for housing, food, transportation, health care, technology, taxes and miscellaneous items. In Central Indiana, Hamilton County has the highest ALICE monthly survival budget for older adults, at $2,526 for single-adult and $3,814 for two-adult households. Meanwhile, Shelby County has the lowest ALICE survival budget for older adults, at $2,074 and $3,234. These budgets are both higher than the Indiana budget, which is $2,002 for a single older adult, and $3,122 for two older adults. Every Central Indiana county has a higher monthly ALICE survival budget than the state of Indiana overall.

The largest expenses for older adult households are housing and health care. Monthly ALICE housing costs are greatest in Hamilton County at $881 and $1,024 for one- and two-adult households, respectively, while they are the lowest in Shelby County, at $599 and $696. Monthly health care costs are greatest in Marion County, at $528 and $1,055 for one- and two-adult households, respectively, while they are lowest in Johnson County, at $459 and $917. More detail on county-specific expenses may be found in the data appendix, located here.

Impact of Housing Costs on Financial Stability

Because of a relatively high cost proportional to the typical household budget, housing costs can place a great deal of financial stress on older adult households. When 30 percent or more of its income is spent on housing costs, a household is considered housing-cost burdened. When 50 percent or more of its income is spent on housing costs, a household is considered severely housing-cost burdened.32 In 2020, 23 percent of the younger-old in Central Indiana were housing cost-burdened, as were 29 percent of the middle-old and 34 percent of the oldest-old.33 For older adults overall, this represents a modest decline since 2014, dropping from 29 percent to 27 percent in Central Indiana. Eleven percent of the younger-old were severely housing-cost burdened, as were 12 percent of the middle-old and 34 percent of the oldest-old. The overall proportion of older adult households who are severely housing-cost burdened changed little from 2015 to 2020. For more on housing costs and challenges affecting older adults, please refer to the Housing section of this report.

Needs Faced by Older Adults

In Central Indiana, over two in five (41 percent) of respondents to the Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults age 60 and older (CASOA) reported that finding affordable health insurance was at least a minor problem for them over the past year, an improvement of nine percentage points since 2017.34 35 Older adults participating in focus groups across the Central Indiana region also voiced concern about their ability to afford healthcare. To qualify for Medicare, an individual must be 65 years old, unless they are a dialysis patient or have a qualifying disability.36 The younger-old may try to access Medicaid but may not qualify based on income. Adults from this age group express frustration that qualification for Medicaid is based on gross income rather than net income, resulting in disqualification for some patients who would otherwise qualify.37

Though all older adults who participated in focus groups alluded to finances, those with lower incomes most consistently identified healthcare coverage as an issue. In addition to healthcare, specific financial management concerns involved balancing expenses such as housing, transportation, and food. Some older adults, particularly those with lower incomes, rely on monthly trips to nearby food pantries to bridge the gap between their monthly incomes and expenses. Most housing and transportation expenses are due to the cost of maintenance beyond monthly payments. These trends were especially true for older adults living in lower-income neighborhoods in Indianapolis. Survey data of Central Indiana adults age 60 and older reveals that more than two-fifths (42 percent) report that having enough money to meet daily expenses was at least a minor problem during the previous year, up six percent from 2017, with similar difficulties noted statewide.38 39 For further discussion of housing, transportation, and food issues for older adults in Central Indiana, see those respective sections of this report.

Inflation and Fixed Incomes

Key informants identified that changes in Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) policies have increased the financial instability for older adults relying heavily on fixed income and government assistance programs. When inflation is high, increases in payments tend to lag slightly behind inflation. According to the Social Security Administration, SSI monthly payments of $794 increased by 1.3 percent from 2020 to 2021, which is consistent with the December 2019 to 2020 inflation rate of 1.4 percent.40 41However, in 2022, SSI monthly payments to an eligible individual increased to $841, an increase of 5.9 percent from 2021, while the rate of inflation in 2021 was 7.0 percent. The SSI monthly payments will increase by 8.7 percent in 2023, although inflation is currently at 8.2 percent and still rising in 2022.42

Employment

Access to technology is often crucial in today’s job market as technology may be required to secure a job, perform job responsibilities, or both. For older adults, particularly those under the age of 85 who have yet to retire or are re-entering the workforce after retirement, gaps in technology skills create a substantial barrier to finding employment, especially for those who previously worked blue-collar jobs. One key informant service provider described the sense of fear that overcomes many older adults when confronted with technology, and their resistance to learning computer skills. This provider estimated that 90 percent of the program’s primarily working-class participants possess few to no computer skills. They may also lack the skills necessary to perform well in jobs. This creates a situation in which older adults increasingly struggle to access employment opportunities which assist with affording basic needs. A survey of Central Indiana adults age 60 and older revealed that in 2021, 35 percent had at least some difficulty finding work while retired, an increase of five percent from 2017.43

In Central Indiana, a greater proportion of older adults pay more than 30% of their income on housing costs compared to the rest of Indiana.

The oldest old (age 85+) are most likely to be paying more than 30 percent of their income towards housing.

Four out of ten older adults (aged 60+) in Central Indiana report some sort of difficulty with meeting daily financial needs.

Income support 2-1-1 calls in Central Indiana from adults age 60 and over were most often related to Food Stamps/SNAP Applications in 2021

2-1-1 Calls for Assistance

2-1-1 is a helpline service providing information and referral to health, human, and social service organizations. In 2019 within Central Indiana, there were 1,097 calls to 2-1-1 from adults age 55 and over for the top ten ranked needs of income support.44 In 2021, for adults age 60 and over within Central Indiana, this number of calls decreased to 948 for the same ten income support related needs. Three of the most frequently requested types of assistance in 2021 were those that specifically target the needs of older adults—Medicaid Applications, Social Security Disability Insurance, and Medicare. These requests for senior services represented a relatively small percentage of calls though. In contrast, over half of all requests from older adults were for assistance with application for the Federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), indicating that food insecurity is of great concern to older adults experiencing financial instability.

- According to the American Community Survey (2019), “total income” includes “wage or salary income; net self-employment income; interest, dividends or net rental or royalty income or income from estates and trusts; Social Security or Railroad Retirement income; Supplemental Security Income (SSI); public assistance or welfare payments; retirement, survivor, or disability pensions; and all other income.”

- An older adult household is defined as a household in which at least one older adult age 55 or older lives

- Unless otherwise specified, all PUMS data discussed in this report section are five-year estimates, ending in the year mentioned in the text, unless otherwise specified (e.g., ”2020” refers to 2016-2020 estimates

- PUMS data is released at the geographic level of PUMA (Public-Use Microdata Area). PUMAs must contain a minimum of 100,000 people and thus vary in geographic size. As a result, when using PUMS data, the Central Indiana region contains Putnam and Brown counties in addition to the eight Central Indiana Community Foundation (CISF) Central Indiana counties of Boone, Hamilton, Hancock, Hendricks, Johnson, Marion, Morgan, and Shelby.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “2016-2020 American Community Survey Five-Year Public Use Microdata Samples [SAS Data File].,” 2020, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/microdata/access.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “2016-2020 and 2011-2015 American Community Survey Five-Year Public Use Microdata Samples [SAS Data File].”

- Anthony Damico and 2018, “How Many Seniors Live in Poverty? - Issue Brief,” KFF (blog), November 19, 2018, https://www.kff.org/report-section/how-many-seniors-live-in-poverty-issue-brief/.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Supplemental Poverty Measure, Poverty in the United States: 2021.” 2022, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2022/demo/income-poverty/p60-277.html

- Nine focus groups with older adults were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. The focus groups composed of older adults were assembled with the identification and recruitment assistance of community service providers. These focus groups were conducted by researchers, in person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and by Zoom after the pandemic began. The questions asked of the focus group participants were discussed and agreed upon by research faculty and staff.

- Thirty-five key informant interviews with caregivers and service providers were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. Public and not-for-profit sector leaders and service providers who are knowledgeable about service systems and issues pertaining to older adults in Central Indiana were identified and interviewed as key informants during report preparation.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “2016-2020 American Community Survey Five-Year Public Use Microdata Samples [SAS Data File].”

- U.S. Census Bureau

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Housing Cost Burden Among Housing Choice Voucher Participants | HUD USER,” accessed January 14, 2021, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr-edge-research-110617.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “American Community Survey, One-Year Average.”

- Stephen Miller CEBS and Stephen Miller CEBS, “Black Workers Still Earn Less than Their White Counterparts,” SHRM, June 11, 2020, https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/compensation/pages/racial-wage-gaps-persistence-poses-challenge.aspx.

- “The Retirement Crisis Facing Black Americans | Aging | US News,” accessed January 28, 2021, https://money.usnews.com/money/retirement/aging/articles/the-retirement-crisis-facing-black-americans.

- “The Retirement Crisis Facing Black Americans | Aging | US News.”

- “Social Security and People of Color | National Academy of Social Insurance,” accessed January 28, 2021, https://www.nasi.org/learn/socialsecurity/people-of-color.

- Laurie Goodman and Christopher Mayer, “Homeownership Is Still Financially Better than Renting,” Urban Institute, February 21, 2018, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/homeownership-still-financially-better-renting.

- Hillier, Amy E. “Residential Security Maps and Neighborhood Appraisals: The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and the Case of Philadelphia.” Social Science History, vol. 29, no. 2, 2005, pp. 207–233. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40267873

- Adam Parker aparker@postandcourier.com, “Wealth Gap: Examining the Root Causes of Poverty among African Americans,” Post and Courier, accessed January 28, 2021, https://www.postandcourier.com/news/local_state_news/wealth-gap-examining-the-root-causes-of-poverty-among-african-americans/article_89406f92-e7b0-11ea-894e-73687a88cf63.html.

- “Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances,” accessed January 28, 2021, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.htm.

- Adam Parker, “Wealth Gap: Examining the Root Causes of Poverty among African Americans,” Post and Courier, November 9, 2020, https://www.postandcourier.com/news/local_state_news/wealth-gap-examining-the-root-causes-of-poverty-among-african-americans/article_89406f92-e7b0-11ea-894e-73687a88cf63.html

- U.S. Census Bureau, “2015-2019 American Community Survey Five-Year Public Use Microdata Samples [SAS Data File].”

- “2017 Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics Origin-Destination Employment Statistics (LODES)” (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.), https://lehd.ces.census.gov/data/#lodes.

- “2017 Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics Origin-Destination Employment Statistics (LODES).”

- U.S. Census Bureau, “2016-2020 American Community Survey Five-Year Public Use Microdata Samples [SAS Data File].”

- “Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Benefits | SSA,” accessed January 28, 2021, https://www.ssa.gov/benefits/ssi/.

- U.S. Census Bureau, “2016-2020 American Community Survey Five-Year Public Use Microdata Samples [SAS Data File].”

- “Policy Basics: Supplemental Security Income,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 13, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/research/social-security/policy-basics-supplemental-security-income.

- United Way of Northern New Jersey, “ALICE Research Center: Indiana,” 2020, https://www.unitedforalice.org/indiana.

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “Housing Cost Burden Among Housing Choice Voucher Participants | HUD USER.”

- U.S. Census Bureau, “2016-2020 American Community Survey Five-Year Public Use Microdata Samples [SAS Data File].”

- National Research Center, “CICOA Aging and In-Home Solutions Full Report,” Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (TM) (Boulder, CO: National Research Center, 2017).

- National Research Center, “CICOA Aging and In-Home Solutions Full Report,” Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (TM) (Boulder, CO: National Research Center, 2021).

- Digital Communications Division (DCD), “Who Is Eligible for Medicare?” Text, HHS.gov, June 7, 2015, https://www.hhs.gov/answers/medicare-and-medicaid/who-is-elibible-for-medicare/index.html.

- Gross income is a person or household’s total income, while net income is gross income minus taxes and deductions.

- National Research Center, “CICOA Aging and In-Home Solutions Full Report,” 2017.

- National Research Center, “State of Indiana Full Report,” Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (TM) (Boulder, CO: National Research Center, 2021).

- U.S. Social Security Administration, “SSI Federal Payment Amounts,” accessed November 9, 2022, https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/SSIamts.html.

- “Consumer Price Index: 2020 in Review: The Economics Daily: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics,” accessed January 28, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2021/consumer-price-index-2020-in-review.htm.

- Consumer Price Index, accessed November 9, 2022, https://www.bls.gov/cpi/.

- National Research Center, “State of Indiana Full Report,” Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (TM) (Boulder, CO: National Research Center, 2021).

- “Indiana 2-1-1 Needs Data,” n.d. Indiana 2-1-1 data analysis is provided by SAVI Community Information System and the Indiana 2-1-1 data dashboard. 2-1-1 is a free and confidential service that helps Hoosiers across Indiana find the local resources they need. When a client calls 2-1-1 for help, this is referred to as an interaction. During each interaction, a client may communicate one or more needs, related to a single problem or multiple problems. When a call is received by 2-1-1, it is placed in one or more categories, depending on the nature of the need(s) expressed by the caller. For example, if a caller requests a referral for a food pantry, a referral for transportation to help get to that pantry, a referral for donated clothing, and a referral for a soup kitchen, the call is identified as a single, unique call related to food needs, transportation needs and material assistance needs. Even though there are two different food-related needs expressed, the call is only counted as a single call for food-related help. In the 2019 dataset, 75% of caller data specified client age, while the remainder did not. In this report, only data with the age of the client (between 55 and 105 years old for 2019, and between 60 and 105 years old for 2021) was used.