Aging in Place

Many people wish to grow older in their own homes rather than in an institutional setting. To accomplish this, it is important to have the means to maintain a home, perform activities of daily living, and feel comfortable in their communities.

Most adults wish to remain in their own homes as they age, rather than moving to an institutional setting. To accomplish this, it is important for older adults to have the means to maintain a home, perform activities of daily living, and feel comfortable in their communities. This section of the report discusses aging in place in both homes and communities. Key questions and findings include:

WHO MAY NEED ASSISTANCE TO AGE IN PLACE?

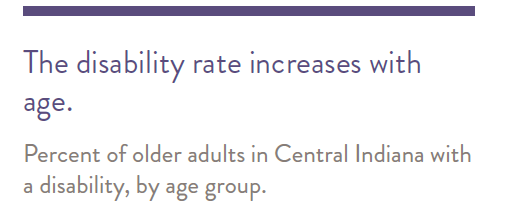

• In Central Indiana, 18 percent of individuals age 55-64 have a disability. The disability rate increases to 29 percent for those age 65-84 and to 66 percent for those age 85 and over.

ARE INDIVIDUALS AWARE OF AVAILABLE SERVICES AND SUPPORTS?

• Only one-quarter of older adults say information is available about services to assist them with remaining in their homes and communities as they age.

IS CENTRAL INDIANA A GOOD PLACE FOR OLDER ADULTS TO LIVE?

• Most older adults in Central Indiana (84%) believe their communities are a good place to live. However, a majority of older adults feel negatively about built environment issues such as the availability and accessibility of high-quality housing, public spaces, mixed-use neighborhoods, and public transit.

AGING IN PLACE AT HOME

The majority (77 percent) of older adults in the United States wish to stay in their current residence for as long as possible as they age.1 To accomplish the goal of “aging in place”, some older adults need assistance. For many, managing a chronic disease or coping with a disability is focal to their aging experience.

As defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a disability is any impairment that makes it more difficult for a person to do certain activities and participate in the world around them.2 In Central Indiana, 18 percent of individuals age 55-64 have a disability. This rate increases to 29 percent for those age 65-84, and to 66 percent of those age 85 and overCenters for Disease Control and Prevention.3 The incidence of chronic disease also increases with age. For older adults with disabilities or chronic disease, assistance with performing routine activities can be essential if these adults are to safely age in place.

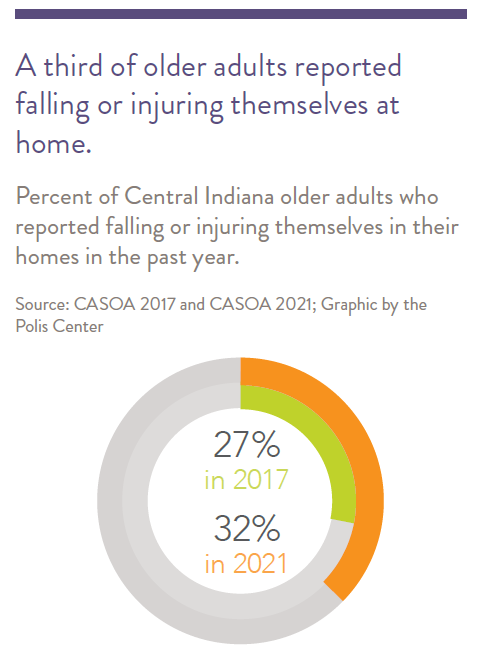

In 2021, nearly half of older adults in Central Indiana reported that maintaining their homes (57 percent) or yards (45 percent) was at least a minor problem. Nearly two-thirds (65 percent) reported that doing heavy or intense housework was at least a minor problem. These challenges can result in injury. In Central Indiana, 32 percent of surveyed older adults reported falling or injuring themselves in their homes during the past year, up from 27 percent in 2017.4

Home modifications are also often needed to allow older adults to safely age in place. Financial assistance through grants or home equity products can pay for home modifications for some low-income homeowners, but renters are unlikely to have these opportunities. Without government incentives or mandates, property owners of rental housing are unlikely to make these changes.5 People of color are more likely to be affected by challenges related to aging in place, as they are less likely to own their homes than White households. 6

Long-Term Systems and Supports

Long-term services and supports (LTSS) are a broad range of supportive services provided formally by professionals or informally by unpaid family and friends to help older adults and people with disabilities. LTSS can be provided in a person’s home, in a community-based setting, such as an assisted living facility or adult day care, or in an institutional setting, such as a nursing home. Communitybased LTSS are designed to allow older adults to age at home or in local settings.7 Such programs include the Medicaid Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) Waiver, Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), Home Options to Institutional Care for the Elderly and Disabled (CHOICE), and Older Americans Act (OAA) programs. See the Healthcare chapter of this report for more details about these programs.

n

n

n

n

AVAILABILITY OF SUPPORT SYSTEMS

In 2020, the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) ranked Indiana 44th in the nation for its overall LTSS system,.8 up from 51st in 2017.9 While Indiana historically has been at the bottom of LTSS state rankings, its ranking compared to other states generally has been improving since 2017. Based on the 2023 LTSS Scorecard, just released in September 2023, Support for Family Caregivers is the only measure for which Indiana is still in the bottom quarter of states. However, it is noted that the scoring and methodology for the LTSS rankings changed in 2023, making direct comparisons to previous years difficult.

The 2021 Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (CASOA™) 10 also revealed a need for improved support in Indiana, including Central Indiana.11 Only 43 percent of those surveyed in Central Indiana reported that the services provided to older adults in their communities are excellent or good, which is an 11-point decrease from the 2017 survey.

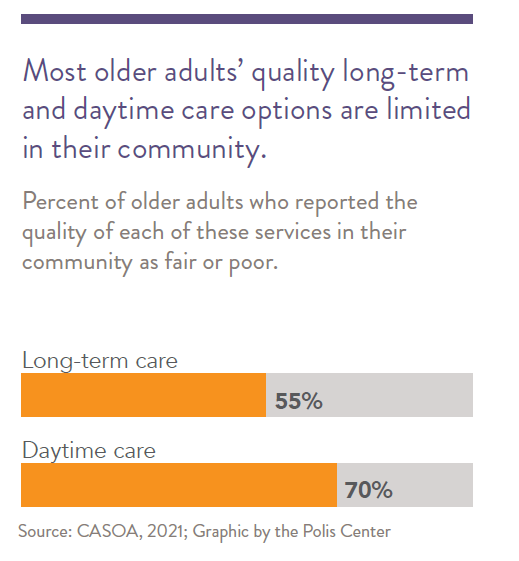

Seventy percent of CASOA respondents believed that the availability of daytime care options for older adults in their communities is fair or poor, and 55 percent believed the availability of long-term care options is fair or poor. Two thirds (67 percent) of older adults said not knowing about available services in their community is a problem.

LTSS Reforms

The Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA) is implementing reforms to the administration of LTSS under Medicaid, with goals to deliver more care and services at home, increase the quality of care through care coordination, and lower costs per person. As of 2023, twenty-five other states have implemented similar reforms, called managed long-term services and supports (mLTSS) programs.12

The case for reform is driven by demand for HCBS and rising LTSS costs. An FSSA presentation outlining Indiana’s LTSS reforms states that most people prefer home-based care, but few receive it, and costs for institutional care are disproportionately high. LTSS spending accounts for a quarter of Medicaid costs in Indiana, and most of that cost is still for institutional care.13

Advocates for mLTSS hope the reforms will reduce costs and incentivize quality care.14 Some studies have found positive benefits for aging in place among established mLTSS programs, although outcomes vary across states 15 16 17 See the Health Care and Caregiving chapters for more details on proposed reforms.

FSSA anticipates the mLTSS program will launch in 2024 and will serve over 120,000 Hoosiers in the initial years of its implementation.18 By 2029, FSSA expects it will serve 165,000 Hoosiers.

n

n

COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVE: ACCESSING SUPPORT

Key informants, including direct service providers, believe many older adults do not receive needed assistance because they are unaware of its availability.19 Even when they were aware that services existed, distrust or pride on the part of an older adult or their caregiver could act as a barrier to receiving these services. Fear was another factor identified by key informants as an element that keeps older adults from seeking services or help. Key informants described many reasons for their fear, but the reasons often included fear of being removed from their home if seen as being incapable of living alone, fear of being a victim of a burglary or other type of crime, or fear of the current world at large, including pandemic fears. See the Safety and Abuse chapter for related discussion.

Key informants suggested that a solution to this problem could include provision of information and outreach through faith communities, senior centers, group meal sites, meal delivery providers, senior housing units, Rotary Clubs, family caregivers, health care providers, and case managers. Establishing a “clearinghouse” of information for community resources was mentioned, demonstrating that some older adults were not aware that CICOA Aging & In-Home Solutions (CICOA) exists to connect older adults in Central Indiana to community resources, including through the Solutions Guide.

It was noted that when an individual was eligible for and enrolled in either Medicaid HCBS Waiver or CHOICE, the assistance provided under these programs was especially helpful. Concern was voiced about the aging population and if resources would be available to meet the growing need for LTSS as Baby Boomers continue to age.

“Just because you can

[do something], doesn’t mean you should.”Focus group participant

Older adult focus group participants who still lived in their communities viewed maintaining their independence as important to their happiness. Some could depend on a spouse, other family members, or neighbors when they needed assistance with day-to-day living. Common issues of concern were challenges maintaining a household (e.g., keeping sidewalks and driveways clear of snow), obtaining home modifications (e.g., grab bars in the bathroom) and accessing transportation. One participant commented that it was important to know when to ask for help with activities such as cleaning the gutters. Some participants expressed a desire for information about eligibility for supportive services.

WHAT IS BEING DONE?

A No Wrong Door (NWD) system has been adopted in Indiana toward empowering older Hoosiers to make informed decisions, exercise control over their LTSS needs, and achieve their personal goals and preferences.20 The NWD system is a person-centered, coordinated approach initiated by the U.S. Administration for Community Living, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, and Veterans Health Administration to seamlessly connect individuals to the full range of LTSS options. 21

Aging and Disability Resource Centers (ADRs) are the backbone of Indiana’s No Wrong Door approach. ADRs serve as portals for long-term care at the community level. The INconnect Alliance is comprised of fifteen ADRs throughout Indiana. CICOA serves as Central Indiana’s ADR and provides counseling, information, referral services, and functional and eligibility assessments for LTSS. CICOA also functions as the intake mechanism for older adults in Central Indiana accessing services through Medicaid and the Older Americans Act.

Other organizations that assist older adults in Indiana communities to stay in their homes include the Fair Housing Center for Central Indiana, which advocates for universal design requirements to facilitate aging in place, and accessABILITY, formerly known as the Indianapolis Resource Center for Independent Living (IRCIL).

Central Indiana continues to make progress toward facilitating aging in place through opportunities like managed LTSS reforms. Opportunities exist to expand information and outreach activities resulting in increased awareness and access to services for those who need and desire support.

AGING IN PLACE IN COMMUNITIES: SENSE OF PLACE

“Sense of place” is a multidisciplinary concept that can include elements such as a person’s physical and emotional connection to the environment around them.22 When older adults live in a neighborhood that is familiar to them, because it increases their satisfaction with that area, because it improves their ability to navigate their surroundings in those environments and reduces the anxiety related to activities within them.23 In unfamiliar environments, older adults can feel more connected and comfortable when aesthetics are appealing and when usability and accessibility are sufficient to facilitate independence. Thus, how they experience “place” becomes very important. 24 Changes to the physical environment can lead to a sense of loss for older adults. 25 Indeed, place attachment is related to social wellbeing. A change in place can lead to a reduction in social wellbeing among older adults. 26 This is particularly true for lower-income households that live in areas of gentrification, where sense of place can be lost as the surrounding physical environment changes.27

See the Social Wellbeing section of this report for further discussion of the factors that impact the social wellbeing of older adults.

CENTRAL INDIANA COMMUNITIES ARE GOOD PLACES TO LIVE

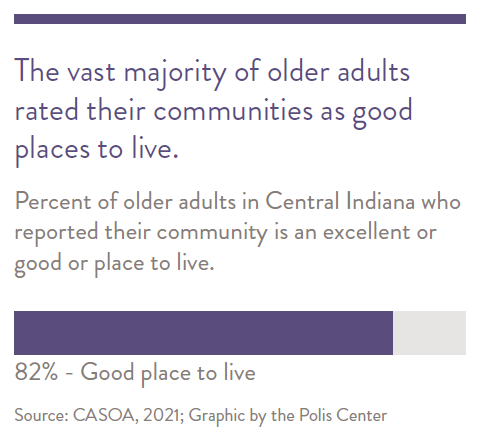

Data from the Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (CASOA™) revealed that most older adults in Central Indiana had reasonably high satisfaction with their communities as places to live and retire. Eighty-two percent of respondents rated their communities as excellent or good places to live, and three out of four (75 percent) reported they were very or somewhat likely to recommend living in their communities to other older adults.

Although a large majority of survey respondents (76 percent) indicated they were very or somewhat likely to remain in their communities throughout retirement, a smaller majority (67 percent) rated their communities as excellent or good places to retire. The difference between these responses suggests that some older adults may prefer to retire elsewhere but do not think they have the option to do so.

Of concern are the one in three (33 percent) older adults who rated their communities as only fair or poor places to retire. Multiple factors influenced whether older adults considered their community a good place to live and retire. As discussed in other sections of this report, physical factors such as safety, transportation, access to high quality food, housing, health, and social services influenced the perceptions of older adults about their communities.

As discussed in other sections of this report, physical factors such as safety, transportation, access to high quality food, housing, health, and social services influenced the perceptions of older adults about their communities.

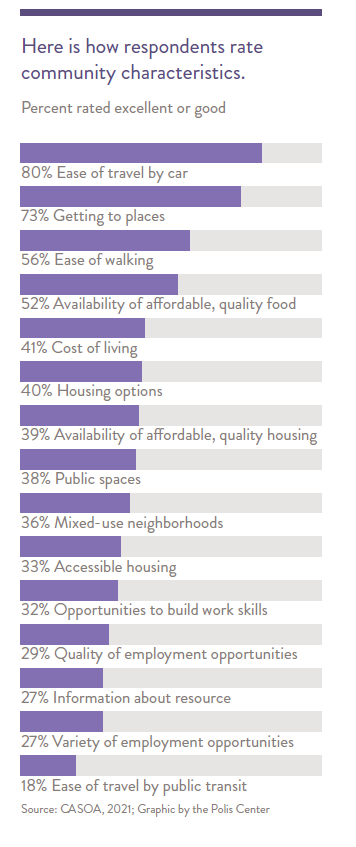

When asked to rate specific characteristics of their community, respondents tended to be more critical: Only four characteristics received mostly positive ratings. Ease of travel by car was viewed positively, as was the related issue of getting to places. A slight majority of respondents viewed ease of walking and access to affordable, quality food positively. On the other hand, only four out of ten older adults viewed the cost of living or the availability of affordable, quality housing favorably.

The way homes and communities are built can facilitate or discourage aging in place. Mixed-use neighborhoods with multiple transportation options make it easier for people to navigate life’s needs without driving. While most older adults said it was easy for them to travel by car, 20 percent rated ease of travel by car as fair or poor. Accessible homes allow people to remain in their house longer and without costly renovations. Unfortunately, these characteristics were rated poorly by most Central Indiana older adults.

COMMUNITY PERSPECTIVE: SENSE OF PLACE

According to service providers and other key informants, location-related aspects limit opportunities for older adults to interact within their communities. For instance, distance between senior centers and community events prevented some from visiting. Additionally, a decline in neighborhood safety limited entertainment opportunities in some areas – older adults could not sit outside as frequently as in the past, especially if they perceived it was not safe to do so. This could be because their surroundings have changed, and they were not as familiar with their neighbors as they once were.

Focus groups of older adults discussed changes they saw in their neighborhoods. Several participants in both Hamilton and Marion counties discussed the impact of gentrification on their neighborhoods. One noted that developers wanted to raze her home and build expensive homes in its place. Another enjoyed living in her neighborhood when it was more racially diverse; however, as home values increased, diversity decreased and many older adults in the area feared being displaced because they could not afford increased property taxes. This participant mentioned that she missed the way her neighborhood used to be, particularly her neighbors who have left. To learn more about the challenges residents of color, particularly Black older adults, face when aging in place, please see ‘Highlighting Equity’ at the end of this chapter.

In another focus group, participants believed their neighborhoods were in decline, with a decrease in homeowners and an increase in renters and abandoned homes resulting in disinvestment in the area by its residents. One person noted that an increase in traffic by her home resulted in property damage and trash, and she was searching for programs to assist with repairs. For those residing in Indianapolis and Marion County, the Mayor’s Action Center (MAC) provides a way to report issues and request services (https://www.indy.gov/agency/mayors-action-center ).

A sense of place from their neighborhood is impactful to older adults in Central Indiana, who rely on this to maintain a good quality of life and to remain in their communities for as long as they wish.

n

n

n

n

n

n

Data collection method

Thirty-five key informant interviews with caregivers and service providers and nine focus groups with older adults were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. Public and not-for-profit sector leaders and service providers who were knowledgeable about service systems and issues pertaining to older adults in Central Indiana were identified and interviewed as key informants during report preparation. Focus groups composed of older adults were assembled with the identification and recruitment assistance of community service providers. These focus groups were conducted by researchers, in person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and by Zoom (virtsual format) after the pandemic began. The questions asked of the focus group participants were discussed and agreed upon by research faculty and staff.

VETERANS AGING IN PLACE

Veterans face special challenges with aging in place. Those living at home are more likely to fall or have memory loss, and disability rates are higher among this population.28 In response to these increased needs and a growing older veteran population, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affiars (VA) announced an expansion of home-based care services in January 2022.29 In April 2023, the White House signed an Executive Order that included action to improve access to home-based care for veterans who need support with activities of daily living.30

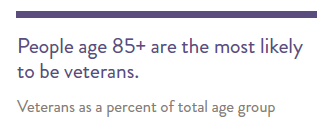

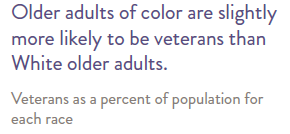

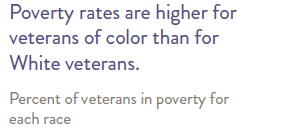

In Central Indiana there are 61,500 older adults who are veterans, 12 percent of that age group (age 55+). Although the majority of Vterans are middle-old, the oldest-old are the most likely to be veterans compared to other age groups. While most older veterans are White, Latinx and Black residents have higher rates of veteran status. In some domains, veterans have fewer vulnerabilities. For example, older veterans in Central Indiana are less likely to experience poverty than non-veterans (6 percent vs 9 percent; ACS 2017-2021 five-year estimates), and veterans over age 75 have lower rates of suicide than civilians in the same age group.31

On the other hand, veterans have higher rates of disability than non-veterans (38 percent vs 27 percent). Veteran status does not eliminate the poverty gap between Blacks and Whites. Black older veterans are twice as likely to experience poverty than other veterans of color, and almost three times as likely to experience poverty compared to White older veterans.

n

n

Barriers to successful aging in place by Black and other older adults of color

Black and other older adults of color face challenges with aging in place due to a variety of individual, interpersonal and community factors:

Individual factors: High prevalence of disabilities

Research has shown that one of the barriers to successfully aging in place is poor health. Because of lower socioeconomic status, people of color experience more barriers to services and have a higher prevalence of disability, meaning they may be less likely to continue living on their own as they age.32

Interpersonal factors: Black older adults are more likely to live with extended family members

One study found that Black older adults are less likely to live with a spouse and more likely to live with extended family members such as children, grandchildren, or other relatives when compared to other older adult households. These multigenerational households may not have the ability to pay for age-friendly home modifications for their elderly family member, as there can be other competing demands for financial resources, such as saving for a child’s education.33

Community factors: Housing Challenges

Black older adults face several housing-related challenges to aging in place. First, Black Americans are less likely to own their homes than White adults.34 One analysis found that nearly one in three Black older adults lived in apartments between 2011 and 2015, meaning they were most likely to be renters. This presents challenges for older adults who may need home modifications, as landlords are only required to make modifications to comply with the Americans with Disability Act and are often unlikely to voluntarily make other modifications due to the costs involved.

Black older adults who own their home also face barriers to successful aging in place. This population was more likely than all other older adults to live in houses built before 1970, which can present health and safety risks such as exposure to lead-based paint, mold, and structural deficiencies which can be costly to repair.35 Gentrification can also be a major problem for homeowners of color, as rising property taxes and cost of living increases can force these older adults to move out of their homes and neighborhoods.36

- Binette J, Farago F. 2021 Home and Community Preference Survey: A National Survey of Adults Age 18-Plus. AARP Research; 2021. doi:10.26419/res.00479.001.

- CDC. Disability and Health Overview | CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published September 15, 2020. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html.

- CDC WONDER Online Database: Provisional Mortality. Accessed June 13, 2023.http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10-provisional.html.

- Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (CASOA): 2021 Report Results for Central Indiana. National Research Center Inc.; 2022. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://cicoa.org/

news-events/research/casoa/. - Johnson JH, Appold SJ. U.S. Older Adults: Demographics, Living Arrangements, and Barriers to Aging in Place. Kenan Institute of Private Enterprise; 2017:30. https:// www.kenaninstitute.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/AgingInPlace_06092017.pdf

- Bucknell, A. (2019). “Aging in Place: For America’s older adults, access to housing is a question of race and class,” Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, October 24. https://www.gsd.har- vard.edu/2019/10/aging-in-place-for-americas-older-adults-access-to-housing-is-a-question-of- race-and-class/.

- Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services. LTSS Overview | CMS. Accessed September 2, 2023.https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/American-Indian-Alaska-Native/AIAN/LTSS-TACenter/info/ltss-overview.

- Reinhard S, Houser A, Ujvari K, et al. Advancing Action, 2020: A State Scorecard on Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Adults, People with Physical Disabilities, and Family Caregivers.AARP Public Policy Institute; 2020:104. https://www.longtermscorecard.org/publications/other-resources/2020-scorecard-release

- Reinhard S, Accius J, Houser A, Ujvari K, Alexis J, Fox-Grage W. Picking Up The Pace of Change:A State Scorecard on Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Adults, People with Physical Disabilities, and Family Caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute; 2017. https://www.longtermscorecard.org/2017-scorecard

- National Research Center Inc. Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults. Accessed September

3, 2023. https://info.polco.us/community-assessment-survey-for-older-adults - National Research Center Inc. Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults. Accessed September 3, 2023. https://info.polco.us/community-assessment-survey-for-older-adults

- Indiana Family and Social Service Administration. About Indiana Pathways for Aging. Indiana Pathways for Aging. Published January 3, 2023. Accessed September 2, 2023. https://www.in.gov/fssa/indiana-pathways-for-aging/managed-long-term-services-and-supports/

- Indiana Family and Social Service Administration. Managed Long-Term Services and Supports Stakeholder Update. Published online November 3, 2021. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.in.gov/fssa/indiana-pathways-for-aging/files/mLTSS-Design-Book-Presentation-11.3.21.pdf

- Tuck KD, Moore JE. Leveraging Opportunities in Medicaid Managed Long-Term Services and Supports (MLTSS). Institute for Medicaid Innovation https://www medicaidinnovation org/_images/content/2019-IMI-MLTSS_in_Medicaid-Report pdf. Published online 2019.

- Neumann LTV, Documet PI. MLTSS and Aging in Place: How Personal Care Services HelpAvoid Nursing Facility Admissions of Older Adults. Innovation in Aging. 2019;3(Supplement_1):S737-S738. doi:10.1093/geroni/igz038.2703Neumann LTV, Documet PI. MLTSS and Aging in Place: How Personal Care Services Help Avoid Nursing Facility Admissions of Older Adults. Innovation in Aging. 2019;3(Supplement_1):S737-S738. doi:10.1093/geroni/igz038.2703.

- Saucier P, Kasten J, Amos A. Do Managed Care Programs Covering Long-Term Services and Supports Reduce Waiting Lists for Home and Community-Based Services?.

- Wysocki A, Libersky J, Gellar J, et al. Medicaid Managed Long-Term Services and Supports:Summative Evaluation Report. Mathematica Policy Research; 2020. Accessed September 2,2023. https://ideas.repec.org//p/mpr/mprres/c11850aef1eb4101b783471917b6fa29.html

- Indiana Family and Social Service Administration. House Enrolled Act 1001- 2021: Managed Long-Term Services and Supports (MLTSS) Report. Published online February 1, 2022. Accessed September 2, 2023. https://www.in.gov/fssa/indiana-pathways-for-aging/files/Feb-22-Implementation-mLTSS-Report.pdf

- Thirty-five key informant interviews with caregivers and service providers and nine focus groups with older adults were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. Public and not-for-profit sector leaders and service providers who are knowledgeable about service systems and issues pertaining to older adults in Central Indiana were identified and interviewed as key informants during report preparation. Focus groups composed of older adults were assembled with the identification and recruitment assistance of community service providers. These focus groups were conducted by researchers, in person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and by Zoom after the pandemic began. The questions asked of the focus group participants were discussed and agreed upon by research faculty and staff.

- Indiana Family and Social Services Administration – Division of Aging, Indiana State Plan on Aging, Federal Fiscal Years 2019-2022, June 2018, Indianapolis, IN. https://www.in.gov/fssa/ files/2019 2022%20Indiana%20State%20Plan%20with%20Attachments%20A-D.pdf.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. No Wrong Door System and Medicaid Administrative Claiming Reimbursement Guidance | Medicaid. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/financial-management/medicaid-administrative-claiming/no-wrong-door-system-and-medicaid-administrative-claiming-reimbursement-guidance/index.html

- Jorgensen, B. S., and Stedman, R. C. (2001). “Sense of Place as an Attitude: Lakeshore Owners’ Attitudes Toward Their Properties,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 21, (2001): 233-248. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2001.0226.

- Fornara, F.,Lai, A.E., Bonaiuto, M., Pazzaglia, F. (2019). “Residential Place Attachment as an Adaptive Strategy for Coping With the Reduction of Spatial Abilities in Old Age,” Frontiers in Psychology 10, article 856, April 24 . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00856

- Phillips, J., Walford, N., and Hockey, A. (2011) . “How do unfamiliar environments convey meaning to older people? Urban dimensions of placelessness and attachment,” International Journal of Aging and Later Life, no. 2: 73-102. https://doi.org/10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.116273.

- Cook, C.C., Martin, P., Yearns, M., Damhorst, M.L. (2009) . “Attachment to “Place” and Coping with Losses in Changed Communities: A Paradox for Aging Adults,” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 35, no. 3: 201-214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077727X06296794.

- Afshar, P.F., Foroughan, M., Vedadhir, A., and Tabatabaei, M.G. (2016) . “The effects of place attachment on social wellbeing in older adults,” Educational Gerontology 43, no. 1: 45-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2016.1260910.

- Shaw, K.S. and Hagemans, I.W. (2015). “’Gentrification without Displacement’ and the Consequent Loss of Place: The Effects of Class Transition on Low-income Residents of Secure Housing in Gentrifying Areas,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39, no. 2: 323-341. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12164.

- Speechley, M., Belfry, S., Borrie, M., Jenkyn, K., Crilly, R., Gill, D. (2005). Risk Factors for Falling among Community-Dwelling Veterans and Their Caregivers. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 24(3), 261-274. doi:10.1353/cja.2005.0083

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VA amplifies access to home, community-based services for eligible Veterans – VA News. Published January 24, 2022. Accessed September 3, 2023. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-amplifies-access-to-home-community-based-services-for-eligible-

veterans/ - Biden Executive Order Provides Sweeping Support to Family Caregivers, Long-Term Care Workers.AARP. Published April 19, 2023. Accessed September 21, 2023. https://www.aarp.org/caregiving/basics/info-2023/biden-executive-order-provides-support-to-caregivers.html

- Karel, M, Wray, L, Adler, G, Hannum, A, Luci, K, Brady, L, McGuire, M. (2020). Mental health needs of aging veterans. Clinical Gerontologist, online preprint https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2020.1716910

- Office of Policy Development and Research. (2013). Aging in Place: Facilitating Choice and Independencehttps://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/fall13/highlight1.html

- James HF, Jr., Lian, H. (2018). “Vulnerable African American Seniors: The Challenges of Aging in Place.” Journal of Housing For the Elderly 32: 135–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2018.1431581.

- Parker, A. (2020). “Wealth Gap: Examining the Root Causes of Poverty among African Americans.” Post and Courier. Accessed January 21, 2021. https://www.postandcourier.com/news/local_state_news/wealth-gap-examining-the-root-causes-of-poverty-among-african-americans/article_89406f92-e7b0-11ea-894e-73687a88cf63.html.

- James & Lian (2018) https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2018.1431581

- Epps, Gretchen, & Luster (2018) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2018.04.018.