Caregiving

Maria and George

Maria and George are a married, Latinx couple living on the near-southside of Indianapolis. George, age 60, has been a middle-school teacher in the Indianapolis Public Schools system for 30 years. Maria, age 58, was a homemaker and the primary caregiver for the couple’s three kids, all of whom are grown and have moved out of the house.

To supplement George’s income, Maria occasionally takes on work from a housecleaning service owned by a longtime friend of hers from church. Maria is also a caregiver for the couple’s granddaughter, Elisa, the only child of one of their daughters. Elisa goes to daycare during the work week, but George and Maria watch her some weekend afternoons—when their daughter is running errands or needs a break—and on workdays, when Elisa needs to be picked up from daycare and her parents are running late.

George’s mother, Sofia, is 85 years old and beginning to experience the early stages of dementia. She lived alone for several years, in her own home not far from Maria and George, after her husband died. But a year ago, after she was unable to renew her driver’s license because of failing eyesight, living alone became increasingly dangerous and impractical. With their kids raised and gone, Maria and George had two spare bedrooms, and it made sense for them to take her in. With George still working full-time, Maria provides most of the care for Sofia. The experience has been deeply rewarding on many levels. Maria’s social circle has expanded as she takes Sofia to events for seniors at the local community center. The two are regulars, as well, at the bi-monthly lunch for seniors at their Catholic Church. The lunches offer good opportunities to talk with friends and meet new people. Maria also feels a strong sense of pride and fulfillment in being a critical source of support to her husband— who struggles to adjust to this new phase in his family’s life—and his mother.

Yet the caregiving has created some new anxieties and hardships for Maria. One is that she is unable to help as much with her granddaughter. With her early-stage dementia and poor eyesight, Sofia needs nearly constant attention. Picking up Elisa at daycare—and watching her on weekends—has become more difficult and requires much more planning than it used to. Caring for Sofia also means that Maria is not able to accept as many jobs with her friend’s cleaning service, which is now only possible when George is free and can care for his mother. So, in addition to depriving Maria of a chance to get out of the house occasionally—something she enjoys very much—caring for Sofia has had a negative impact on the family’s income. At the same time, it has increased their expenses. This combination of stresses is leading Maria to lose sleep. She worries about not only the couple’s finances in the near-term but how Sofia’s dementia will affect her and George’s relationship and finances over the coming years.

- Four out of five older adults in Central Indiana reported assisting a friend, relative, or neighbor.

- One third of older adults provide care to someone age 55 or older.

- In Indiana, there was an estimated $10.8 million in unpaid caregiving services provided for family members in 2021, covering 740 million care hours.

- As many as one fifth of older adults in Central Indiana are

physically, emotionally, or financially burdened by caregiving responsibilities.

- Most adults do not believe support services are available for caregivers.

- Between 2017 and 2021, there was a decline in the share of older adults in Central Indiana reporting caregiving at least one hour per week for other older adults and for other individuals in general.

- The pandemic took a significant toll on caregivers’ mental health. Among respondents to a national survey, at least half report adverse mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, or PTSD. Furthermore, around 30 percent of caregivers considered suicide.

Caregiving of Friends and Loved Ones

Caregiving of friends and loved ones encompasses a variety of activities and levels of assistance depending on the condition of the friend or loved one needing care. Administering care (e.g., assisting with dressing, showering, and medication adherence) can become challenging for an individual to manage alone when such assistance is required on a continuous basis.

In 2021, at least one in five Hoosiers provided regular care or assistance to a friend or family member who had a health problem or disability, with most providing care for a mother or non-relative/family friend.1

In Central Indiana, the share of older adults who reported providing at least an hour of care to someone in the past week was significantly lower in 2021 than in 2017 based on the Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (CASOA).2 This could be due to changes in the survey questions. The 18 to 54 age range was formerly 18 to 59, and 55 or older age range was formerly 60 or older. This could also be impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Surveys were conducted in the fall and winter of 2021, during the COVID-19 surge in the U.S. This could have temporarily reduced older adults’ ability to care for others as they practiced social isolation.

“Who these older adults with dementia are today is not going to be who they are next year. It is very hard to slow this down. These people are not the same person. They think we have more effective medicines than we do. We can’t change the progression of the disease. The medicines are not that great. It is better to have help in place. It is about staying active and engaged…”

Diane and Pat Healey, Indianapolis Geriatricians

Older adults often care for other older adults, such as a spouse, friend, or family member. Those in care may have a cognitive disorder, physical disability, comorbidities, or other health problems that arise through the aging process. Mild cognitive impairment, dementia or Alzheimer’s disease are common cognitive disorders that require a caregiver. About 13 percent of caregivers in Indiana report caring for someone with Alzheimer’s.3 Often 24-hour-a-day care when the impairment is more severe. Caring for someone with an impairment can be a demanding and unrelenting job for the caregiver depending on caregiver’s knowledge of the illness, acceptance of the outcome of the illness, available resources, and ability to accept assistance in caring for the friend or loved one with the impairment. Aid in caring for an individual with cognitive impairment may be provided by other family members, friends, or outside agencies structured to provide services to those in need. The support received can benefit the caregiver in numerous ways including emotional respite, financial planning and management, health care system navigation, and other social services.

Older adults can also provide care for other older adults with physical impairments. Physical impairments are typically due to chronic illness (such as arthritis or a stroke) and can have varying degrees of impact on the day-to-day life of the older adult and the caregiver. Activities of daily living that may be influenced by disability include general hygiene activities, dressing, preparing meals, or transferring to bed or to a chair. Assisting friends or loved ones with physical impairments with daily activities also may place a tremendous burden on friends or loved ones over time. Community support is available for caregivers in the form of transportation, home renovations to increase accessibility (e.g., building a ramp or widening a doorway), assistive devices (e.g., cane, walker, or shower chair) for rent or loan, and in-home care (e.g., cooking, cleaning, snow shoveling, or yard work) from a service agency.

Caregivers are a diverse group. Some are paid while many are not. Some are parents caring for children, some are children caring for older parents, and others are community members that volunteer to help provide care. Many are older adults assisting a friend, relative, or neighbor. One in six American workers provide care. Caregiving is more common among people with lower incomes: 21 percent of people earning $36,000 per year provide care compared to 15 percent of those who earn above $90,000.4 A larger share of Black (21 percent) and Latinx individuals (20 percent) provide care than White individuals (17 percent). (See “Highlighting Equity” for more information about Latinx caregivers.) While caregivers are diverse, the responsibility falls more heavily on those who are low-income and are people of color. These groups already face adverse health outcomes, which were exacerbated by systemic problems illuminated through the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are some promising ways to reduce these added stressors and complications for both caregivers and older adults. These include increasing communication using technology, assisting with activities of daily living such as grocery shopping, and providing caregivers with the support they need.5

Reforms to Indiana’s long-term support services (LTSS) system will impact family and friends who are caring for older adults. (See the Health Care chapter for details about this reform.) The managed LTSS (mLTSS) reform in Indiana has raised some concerns. Under the current system, family and friends provide the majority of the LTSS in-home and community-based care. Some critics are concerned this reform will exacerbate the persistent and growing LTSS workforce shortages.6 There is fear that this will increase the burden on family caregivers. Some are concerned mLTSS prioritizes reduced costs for the government more than providing quality health care for older adults.7 Critics say managed care entities have an incentive to offer low quality of services and deny procedures to boost profits. There is also pushback from healthcare providers due to low reimbursement fees and increased administrative burden.8 Indiana FSSA is attempting to allay these concerns by holding stakeholder meetings and soliciting feedback from all the involved entities.

“They are very prideful, but not in a negative way. They are prideful of heritage, families, and they take a lot of pride in what they do. They are prideful as Senior Companions and let people know why they do it. The women are very prideful of what they have accomplished in their life…Pride is part of the way of coping and gets them through hard stuff. Pride and spirituality keep them going every morning.”

Joyce Bleven, Senior Companions

Impact on Caregiver

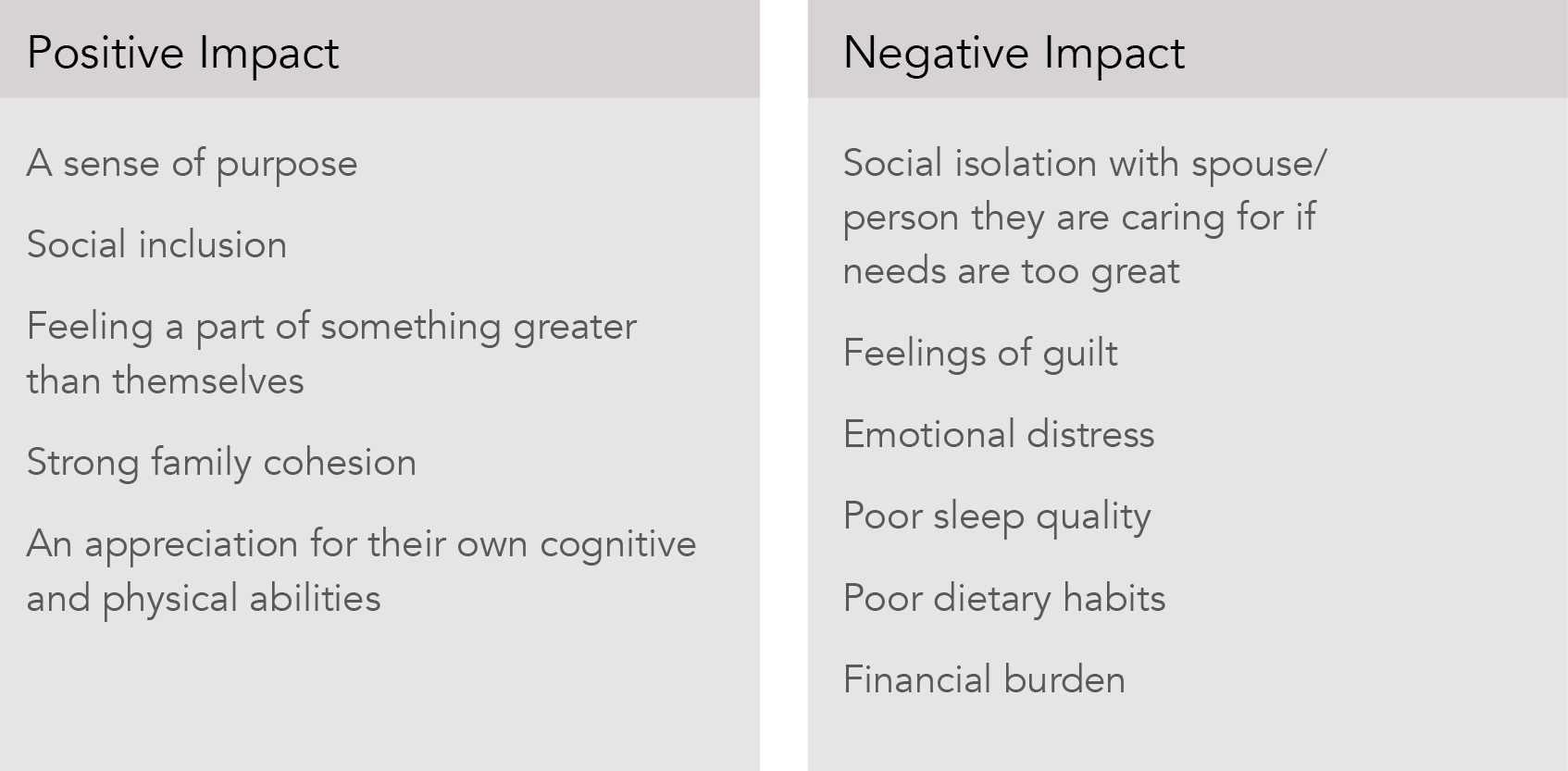

The impact of caregiving on the caregiver is significant, and informants to this report say that it is not unusual for the caregiver to suffer along with their friend or loved one.9 The physical and psychological strain of providing care may become increasingly burdensome and can impact family relationships, friendships, and the caregiver’s ability to participate in activities outside the home. In addition to the negative impact of caregiving, older adults can experience some benefit from caring for friends or loved ones including positive emotions such as compassion, satisfaction, and confidence.

Older adult caregivers who were interviewed for this report indicate positive benefits most frequently when caregiving was a newer or short-term experience or when the individual was not the sole caregiver. Caregivers report positive self-esteem and the ability to build additional skills to better care for their friends or loved ones. Additionally, the need to provide care for a friend or loved one resulted in joining support groups and making new friends who had similar experiences. Support groups could not only provide emotional help but also offer the opportunity for the caregiver to help others. Those who had larger families experienced their families frequently coming together to offer support for a friend or loved one, which provided the opportunity to create new family memories and positive experiences. Finally, informants reported that providing care for a friend or loved one gave caregivers the opportunity to feel more optimistic about their own physical and cognitive abilities.

While caregiving for friends or loved ones in smaller doses can be rewarding and purposeful, ongoing demands can have negative effects for the caregiver. The burdens of 24-hour-a-day care may result in feelings of frustration, irritability, isolation, despair, and exhaustion. Informants reported that older adults caring for spouses often found it difficult to seek external assistance or support. Informants reported viewing the caregiver role as solely their responsibility and not wishing to burden others. Another reason a caregiver may decline to accept outside assistance is a general lack of trust in asking a stranger to care for a vulnerable friend or loved one. Informants also reported that the caregiver’s sense of pride left them feeling that they could manage their caregiving responsibilities alone and may prevent caregivers from seeking outside assistance.

Informal family caregivers are critical in Indiana

Those with disabilities may particularly need caregiving services

Potential Impact on Caregivers

Impact of COVID-19 on Caregivers

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused severe harm to most industries and that includes caregiving for older adults. Caregivers were already a vulnerable group under immense pressure before the virus, but they were pushed even further during the pandemic. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) survey found that caregivers’ mental health took a significant toll during this time. Among respondents, at least half report adverse mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, or PTSD. Furthermore, around 30 percent of caregivers seriously considered suicide. Half of caregivers responsible for both children and adults considered suicide.13 For comparison, a survey from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration in 2015 found the rate at which the general population thought about committing suicide was much smaller (4 percent).14

Impact on Person Being Cared For

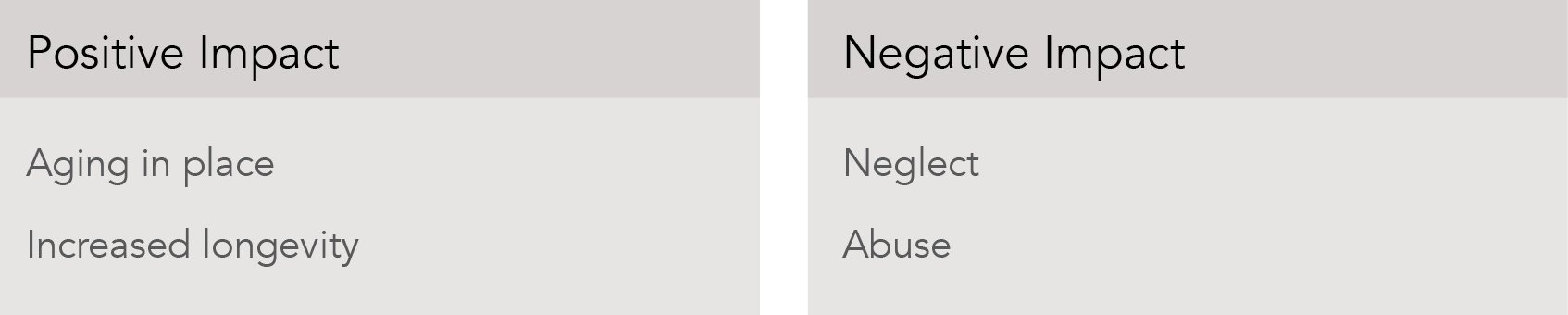

Caregiving demands impact the caregiver and may also influence the person receiving care in both positive and negative ways.

Informants reported that “aging in place” is a well-understood concept. People want to stay in their own homes and as independently as possible for as long as possible. Caregivers help older adults remain in their familiar surroundings.

This is especially helpful for an older adult with cognitive impairments that may find a new living environment disorienting. (For further discussion on aging in place see the associated section in this report.) Informants also report that caregiver support likely increases the longevity of the older adults receiving care and the likelihood that those older adults will remain active not only in their homes but in their communities. Being physically and socially active improves health outcomes.

Potential Impacts on Person Being Cared For

“Being alone is as detrimental to health as cigarette smoking.”

Daniel O. Clark, Indiana University Center for Aging Research

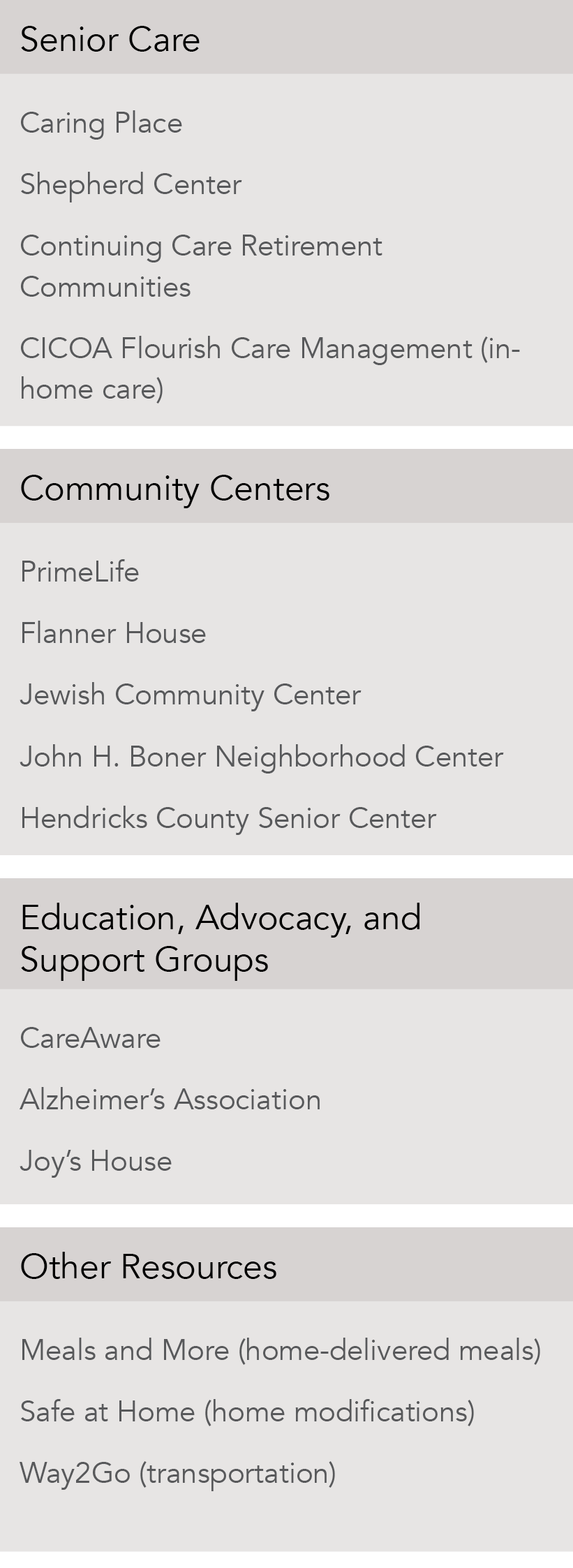

Resources Available to Caregivers

While caregiving can be a rewarding experience, it can also create a stressful, difficult, and exhausting environment for both the caregiver and their friend or loved one. In Central Indiana, there are resources available that offer support, many of which are provided or coordinated by CICOA. The list to the right is not exhaustive but provides examples of services available to caregivers and their friends or loved ones.

All informants for the current report agree that a clearinghouse of services for caregivers and their friends or loved ones would be quite useful. However, not all caregivers or their friends and loved ones were aware that local information and referral organizations exist, such as CICOA Aging & In Home Solutions (CICOA)18 and Indiana 211.19 Informants also report the need for better coordination of services and for agencies to better understand gaps in services and unmet needs. In early 2021, CICOA launched a technology solution, Duett, to match people who need in-home care with providers.20

“We are so fragmented in everything we do. When we look at the continuum of care, you can have a discharge planner and they don’t know they have a case manager… We need to make better use of the Health Information Exchange and better communication, so we are not operating in silos. If policymakers made it so we’re all talking together for betterment of the patient, it would be better.”

Donata Duffy, CICOA

Latinx populations face greater caregiving burdens

Latinx individuals are more likely to provide care for an older adult loved one than any other racial or ethnic group.21 Although Latinx caregivers report higher levels of caregiving satisfaction than White caregivers, 44 percent report feeling stressed and overwhelmed by their caregiving responsibilities.22 Latinx individuals also spend more time and money caring for their loved ones than average.23 Several factors can lead to high rates of caregiving and caregiving burden among Latinx adults, as described below:

Individual factors: High rates of dementia

Compared to non-Latinx Whites, Latinx individuals are at greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s and other dementias. This is due to longer life expectancies and higher rates of chronic disease such as diabetes and heart disease.24 Studies have shown that caregivers of people with dementia experience greater caregiver burden, with roughly 25 percent providing at least 40 hours of care per week to their loved one, compared to only 16 percent of other caregivers.25

Interpersonal: Emphasis on family

A value common among Latinx individuals of various national origins is familism, or the emphasis on and importance of family. Priority is often placed on the interdependence between family members, and support is most often sought within the family system rather than from more formal or institutional supports.26 As a result, one study found that Mexican-American caregivers were the least likely to use formal care for their loved one compared to others.27 It should also be noted that familial care is most often provided by women due to cultural expectations of women as natural caregivers who prioritize the needs of the family first.28

Organizational: Lack of culturally sensitive and Spanish-speaking resources

Only around half of Latinx older adults are proficient in English,29 and 57 percent of Latinx adults report encountering language or cultural barriers when interacting with healthcare providers. Less than half of Latinx adults who participated in a long-term care survey felt that they could easily find nursing homes, assisted living facilities or home health aides that spoke their language, while less than 30 percent felt that these services would provide the food they were used to eating.30 Additionally, Latinx caregivers felt they had a lack of understanding of topics around caregiving, with 41 percent stating they do not understand government programs such as Medicare and SSI, compared to 27 percent who share that they encountered issues with finding educational resources. When asked what Spanish-language resources would be helpful for Latinx caregivers, roughly half mention trainings on stress management, government programs, and caregiving techniques.31

- INDIANA 2021 Codebook Report, Overall version data weighted with _LLCPWT. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. https://www.in.gov/health/oda/behavioral-risk-factor-surveillance-system/

- National Research Center Inc., “Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults: 2021 Report Results for Central Indiana” (Boulder: CICOA Aging and In-Home Solutions, 2021), https://cicoa.org/news-events/research/

- INDIANA 2021 Codebook Report, Overall version data weighted with _LLCPWT. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. https://www.in.gov/health/oda/behavioral-risk-factor-surveillance-system/

- Peter Cynkar and Elizabeth Mendes, “More Than One in Six American Workers Also Act as Caregivers” (2011), https://news.gallup.com/poll/148640/one-six-american-workers-act-caregivers.aspx

- Anna Garnett, Melissa Northwood, and Ruhenna Sangrar, “Older caregivers struggling with extra burdens of home care during COVID-19” (2021), https://theconversation.com/older-caregivers-struggling-with-extra-burdens-of-home-care-during-covid-19-152373

- Managed Long Term Services and Supports: Status of State Adoption and Areas of Program Evolution (n.d.). Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Managed-Long-Term-Services-and-Supports-Status-of-State-Adoption-and-Areas-of-Program-Evolution.pdf

- Hellinger, F. J. (1998). The Effect of Managed Care on Quality: A Review of Recent Evidence. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(8), 833–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.158.8.833

- How Have Long-Term Services and Supports Providers Fared in the Transition to Medicaid Managed Care? A study of Three States. (n.d.). ASPE. Retrieved May 31, 2022, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/how-have-long-term-services-supports-providers-fared-transition-medicaid-managed-care-study-three-1

- Thirty-five key informant interviews with caregivers and service providers and nine focus groups with older adults were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. Public and not-for-profit sector leaders and service providers who are knowledgeable about service systems and issues pertaining to older adults in Central Indiana were identified and interviewed as key informants during report preparation. Focus groups composed of older adults were assembled with the identification and recruitment assistance of community service providers. These focus groups were conducted by researchers, in person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and by Zoom after the pandemic began. The questions asked of the focus group participants were discussed and agreed upon by research faculty and staff.

- Reinhard, S. C., Caldera, S., Houser, A., & Choula, R. B. (2023). Valuing the Invaluable: 2023 Update Strengthening Supports for Family Caregivers. AARP Public Policy Institute. https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2023/3/valuing-the-invaluable-2023-update.doi.10.26419-2Fppi.00082.006.pdf

- National Core Indicators for Aging and Disabilities (NCI-AD) Adult Consumer Survey report. 2019-2020 Indiana results. https://nci-ad.org/upload/state-reports/FINAL_IN_19-20_NCI-AD_state_report.pdf.

- Primarily older adults, from three programs–Medicaid Waivers, the Community and Home Options to Institutional Care for the Elderly and Disabled (CHOICE) Program, and Title III, Older Americans Act (OAA).

- Czeisler, M., Rohan, E., Melillo, S., et al., “Mental Health Among Parents of Children Aged <18 Years and Unpaid Caregivers of Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, December 2020 and February–March 2021” (2021), https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7024a3.htm

- Piscopo, K. and Lipari, R. N., “Suicidal Thoughts and Behavior among Adults: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health” (2016), https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/ NSDUH-DR-FFR3-2015/NSDUH-DR-FFR3-2015.htm

- Lachs, M. S. et al., “Risk Factors for Reported Elder Abuse and Neglect: A Nine-Year Observation- al Cohort Study1,” The Gerontologist 37, no. 4 (August 1, 1997): 469–74, https://doi.org/10.1093/11.15geront/37.4.469.

- Johannesen, M. and LoGiudice, D., “Elder Abuse: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors in Commu- nity-Dwelling Elders,” Age and Ageing 42, no. 3 (May 2013): 292–98, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/ afs195.

- Tatara, T. et al., “The National Elder Abuse Incidence Study,” n.d., 136

- “CICOA Aging & In-Home Solutions | Indianapolis, IN,” accessed February 16, 2021, https://cicoa.org/.

- FSSA, “Indiana 211,” accessed February 16, 2021, www.in211.org.

- Roberts, M., “CICOA Launches Tech Startup For In-Home Care,” Inside Indiana Business, February 3, 2021, https://www.insideindianabusiness.com/story/43287298/cicoa-launches-tech-startup-for-in- home-care.

- “Final-Proceedings-Caregiving-Thought-Leaders-Roundtable-Washington-DC-1.Pdf,” accessed January 26, 2021, http://www.nhcoa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Final-Proceedings-Caregiving-Thought-Leaders-Roundtable-Washington-DC-1.pdf.

- Rote, S. M. et al., “Caregiving Across Diverse Populations: New Evidence From the National Study of Caregiving and Hispanic EPESE,” Innovation in Aging 3, no. 2 (September 9, 2019), https://doi. org/10.1093/geroni/igz033.

- “Status of Hispanic Older Adults: Insights from the Field – Reframing Aging. (2018). https://www.diverseelders.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-Status-of-Hispanic-Older-Adults.pdf“

- “Status of Hispanic Older Adults: Insights from the Field – Reframing Aging. (2018). https://www.diverseelders.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-Status-of-Hispanic-Older-Adults.pdf“

- Brodaty, H. and Donkin, M., “Family Caregivers of People with Dementia,” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 11, no. 2 (June 2009): 217–28.

- Flores, Y. G. et al., “Beyond Familism: Ethics of Care of Latina Caregivers of Elderly Parents With Dementia,” Health Care for Women International 30, no. 12 (December 2009): 1055–72, https://doi. org/10.1080/07399330903141252.

- “Rote, S. M., Angel, J. L., Moon, H., & Markides, K. (2019). Caregiving Across Diverse Populations: New Evidence From the National Study of Caregiving and Hispanic EPESE. Innovation in aging, 3(2), igz033. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igz033 ”

- Flores et al., “Yvette G. Flores , Ladson Hinton , Judith C. Barker , Carol E. Franz & Alexandra Velasquez (2009) Beyond Familism: A Case Study of the Ethics of Care of a Latina Caregiver of an Elderly Parent With Dementia, Health Care for Women International, 30:12, 1055-1072, DOI: 10.1080/07399330903141252 ”

- “Status of Hispanic Older Adults: Insights from the Field – Reframing Aging. (2018). https://www.diverseelders.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-Status-of-Hispanic-Older-Adults.pdf ”

- Okal, T., “Communication and Long-Term Care: Technology Use and Cultural Barriers among Hispan- ics – The Long-Term Care Poll,” accessed January 26, 2021, https://www.longtermcarepoll.org/project/ communication-and-long-term-care-technology-use-and-cultural-barriers-among-hispanics/.

- “Status of Hispanic Older Adults: Insights from the Field – Reframing Aging. (2018). https://www.diverseelders.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-Status-of-Hispanic-Older-Adults.pdf “