Health Care 2022

The health-related needs of older adults are often more complex because of advanced chronic disease and associated disability and require additional attention to care coordination.

Abraham

Abraham recently turned 70 year old and lives with his partner on the near-east side of Indianapolis in a home that they bought 25 years ago. After graduating from high school, working, and saving, Abraham became a small-business owner. He operated a laundromat, a thrift store, and then—for nearly 30 years—a small neighborhood bar. He sold the bar and retired after suffering a fall down a small set of stairs, which injured his knee and required surgery. The fall left him unable to stand for more than a few minutes, or walk more than short distances, without significant pain—which made it impossible for him to keep working at the bar.

Social Security benefits make up nearly all of their household income of nearly $35,000. The small retirement nest egg he built during his working years was drained by the costs of surgery, physical therapy, and related expenses not covered by Medicare. He also takes two prescription drugs to lower his cholesterol and his blood pressure. His primary caregiver for nearly 30 years, who retired 15 months ago, also diagnosed Abraham with pre-diabetes and said he needed to change his diet to avoid developing type 2 diabetes.

Since his surgery and subsequent retirement, Abraham has been covered by both Medicare and Medicaid, which means that most of his healthcare costs are currently covered. Yet he still faces serious health-related stressors and challenges.

One is that he has no hope of recovering the full mobility and mostly pain-free life he had before his fall, and he fears that another fall could leave him wheelchair-bound. A second challenge is that, as a gay Black man, Abraham has not developed a trusting relationship with the new primary care physician he has seen (just twice) since his former caregiver retired. He learned as a young man to be intensely private about his personal life, and he waited several years to reveal his sexual orientation to the previous caregiver. He has not yet done so with the new one. One result is that he feels less motivated to schedule or keep regular doctor appointments, which means he misses out on the kind of preventive care that might slow the progression of his prediabetes and mitigate his risk of heart disease. A third challenge is that Abraham is suffering from depression as he struggles to adjust to retirement, limited mobility, and chronic pain. His lack of a strong relationship with his new primary caregiver is one obstacle to securing a referral to a mental-health professional. The stigma he has encountered as a gay man is another obstacle. He is very aware that counseling could help him cope with his depression. But connecting with a therapist, much less being vulnerable about his struggles, seem like insurmountable challenges.

The health-related needs of older adults are often more complex because of advanced chronic disease and associated disability and require additional attention to care coordination. This section of the report discusses availability and use of health care, home-based services, and community-based services. Key findings include:

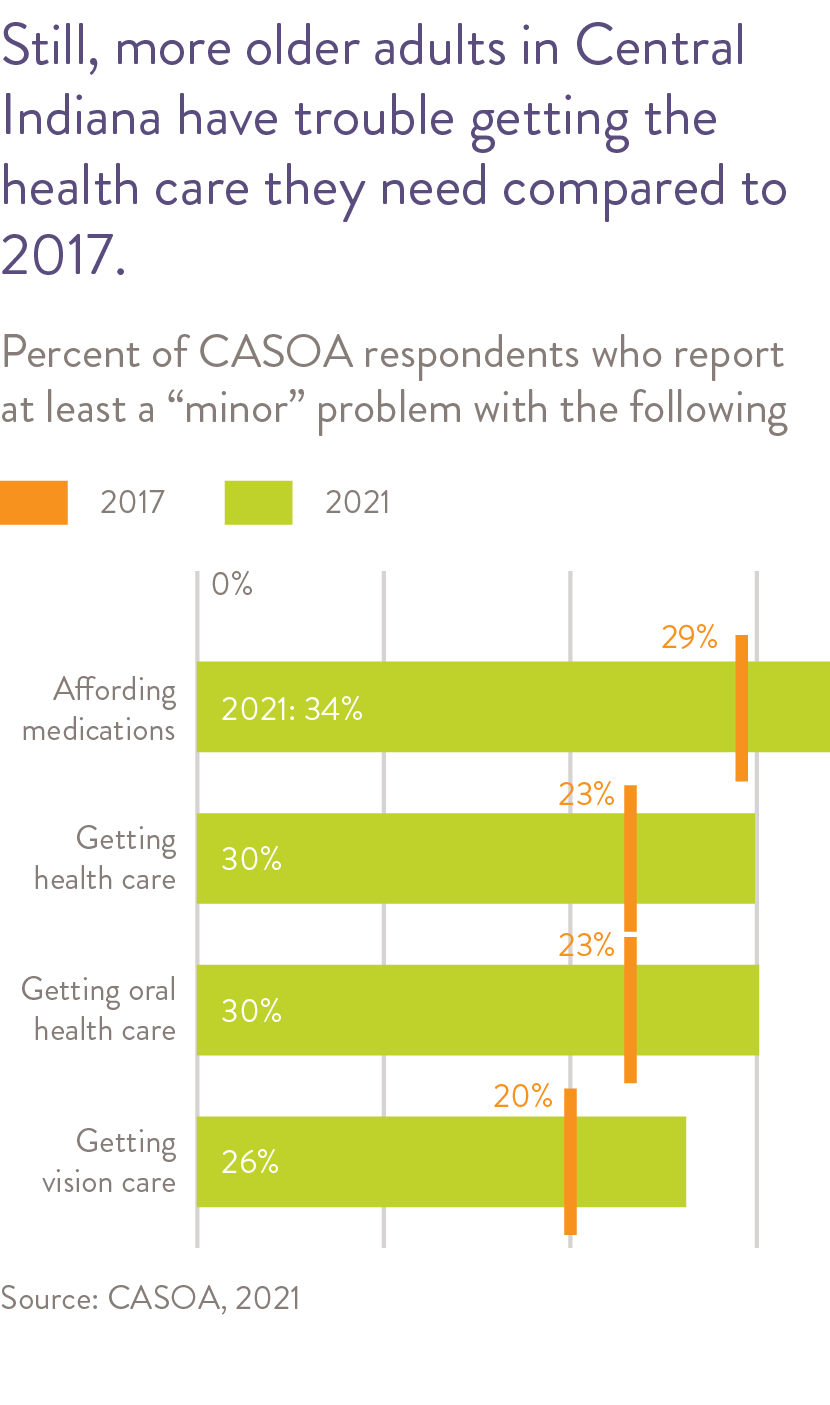

- Most older adults in Central Indiana feel preventative and physical health care is broadly available, but the share who have problems affording health care is on the rise, according to a 2021 survey.

-

Providers identify falls, mental health, dementia and fragmented care as issues that need more resources and attention.

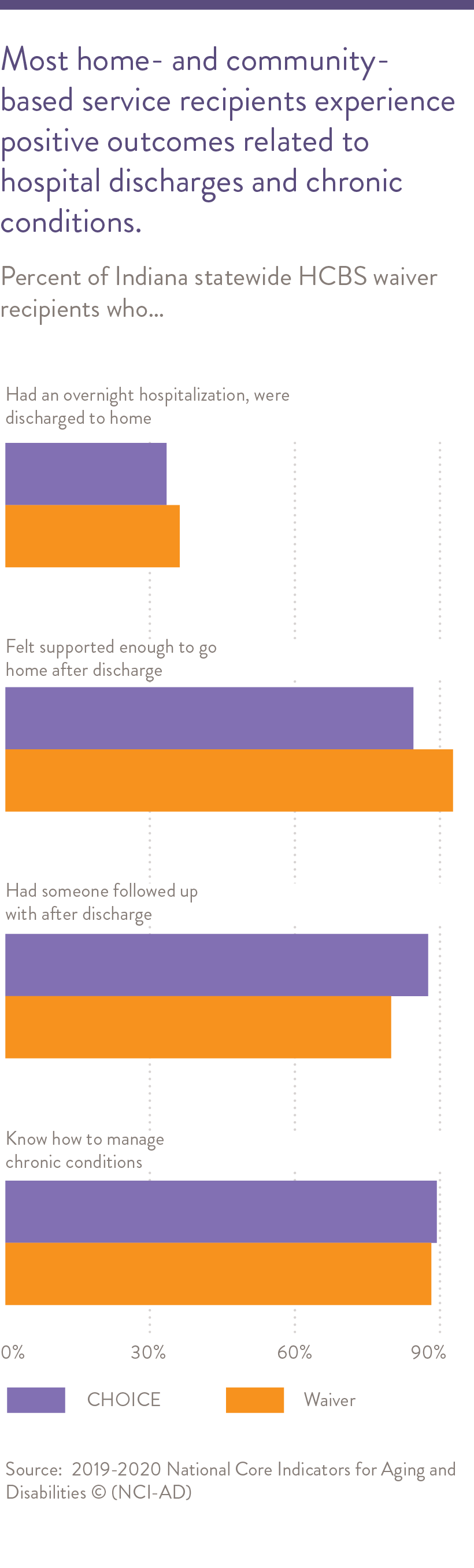

- Recipients of home- and community-based services report positive outcomes for hospital discharges and chronic conditions. Medicaid reforms in Indiana could expand access to these services.

-

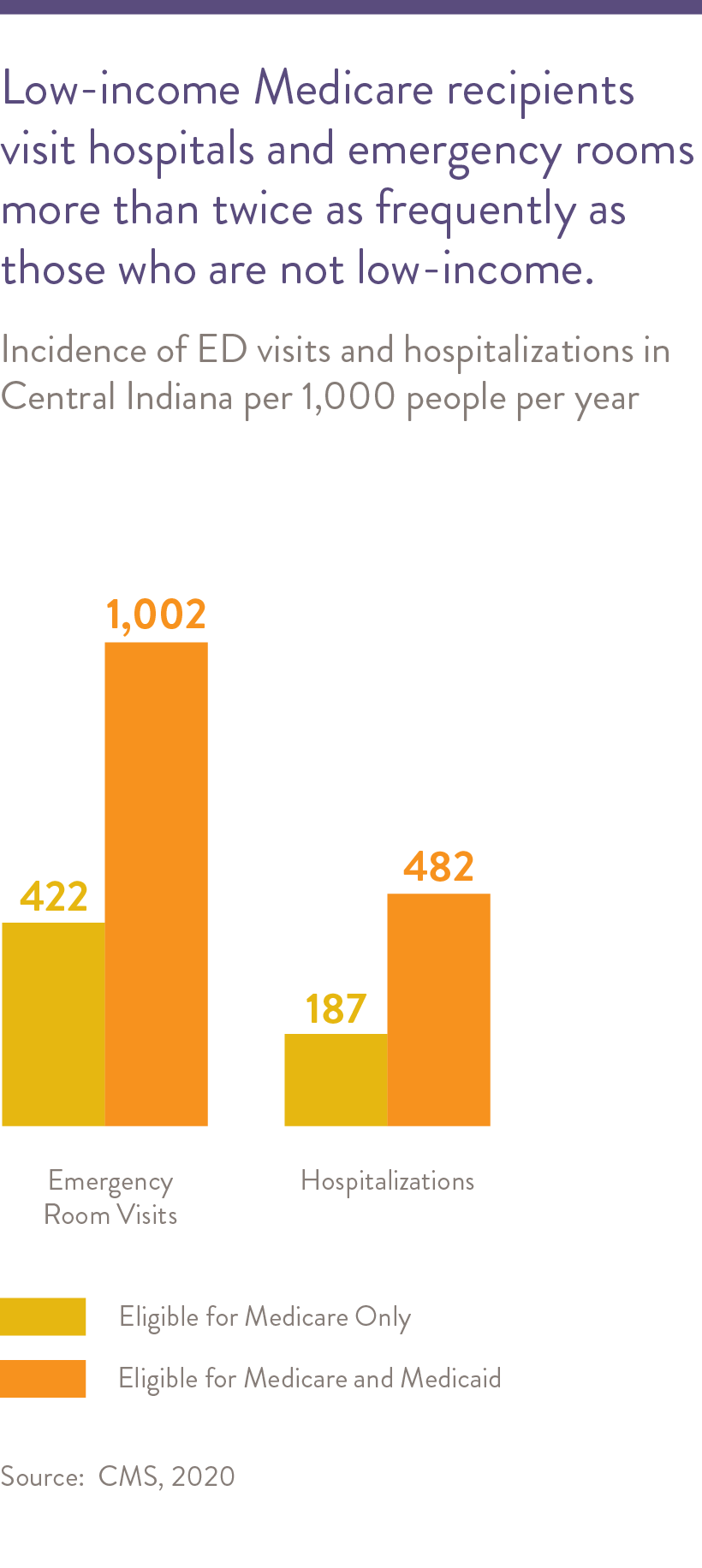

Low-income and other vulnerable Medicare recipients in Central Indiana visit hospitals and emergency rooms more frequently than other Medicare recipients.

-

Indiana’s ratio of residents to physicians improved by 20 percent between 2016 and 2021, but rural areas are still lacking health care providers.

Chronic disease in older adults is often accompanied by disability, high health care utilization, and high health care costs.1 A significant issue that arises with aging and advances in medical capabilities is how to balance the goals of maximizing quantity of life versus quality of life.

Availability of Health Care

Central Indiana is fortunate to have an abundance of health care professionals and health care organizations. The region has more geriatric specialists relative to other areas of the state. (See Data Appendix.) The majority of Central Indiana respondents to the Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults (CASOA™) age 60 and older reported feeling that health care is broadly available.2

However, as with the rest of the country, the number of health care professionals and health care organizations specializing in the care of older adults is not adequate for the aging population.3 In Indiana as of 2021, the ratio of residents per physician in rural areas is 1,070:1 as compared to urban i.e., 433:1.4 These ratios both improved by at least 21 percent since 2016, but these disproportionalities adversely affect the access to care in rural counties where the point of care for most older residents is their primary care practitioner. The lack of availability of specialized geriatric services in these primary health care provider shortage areas coupled with other socio-economic factors like low income further deteriorates the possibility of geriatric health care access.5 Shelby County, for example, has only one healthcare system serving its entire population and no geriatric services available. (See Data Appendix.)

- Falls and the fear of falling (see Health Outcomes section for associated statistics)

- Mental health and emotional issues in older adults, including depression and schizophrenia See Health Outcomes section for associated statistics)

- The need for memory care programs and better treatment and support for persons living with dementia and their caregivers who are friends or loved ones

- Fragmented care and the lack of coordination between hospital discharge planners and community-based case managers

In addition, several of the larger health systems in Central Indiana have established specialized geriatric services proven to result in better outcomes for older adults with complex needs. These services typically involve a team of health care professionals such as a physician, nurse, and social worker. They can also include geriatric emergency department programs, Acute Care for Elders (ACE) hospital consultation, hospital-to-home care transitions programs, outpatient consultation for falls and memory assessment, and office and in-home primary care. Details about the availability of these services in the healthcare systems in Central Indiana are provided in the appendix.

Several hospitals in Central Indiana are working with CICOA to become a Dementia Friends Indiana Hospital and requiring staff to become more familiar with how to appropriately care for persons with dementia. (See Appendix.) The number of geriatrics health care professionals and services has grown in Central Indiana which has helped to address these issues. However, there is still limited capacity compared to the need that exists. For example, a geriatrician is a physician who is specially trained to evaluate and manage the unique health care needs and treatment preferences of older adults. In 2018, there were only 87 board certified geriatricians in practice across all of Indiana.8 This reflects a nationwide issue.9

Both Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM) and St. Vincent Hospital offer training programs for physicians desiring to specialize in geriatric medicine. IUSM also hosts a U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration funded Geriatrics Workforce Enhancement Program that aims to provide education and training in geriatric care principles to medical, nursing, and social work trainees as well as staff of local primary care practices.

Long-Term Services and Supports

Long-term services and supports (LTSS) are the personal care assistance that many people need as they grow older.10 LTSS includes assistance with self-care tasks, like bathing and dressing, and with daily living tasks, like cooking or managing medication. This work is provided by both paid and unpaid caregivers. Older adults who need assistance with activities of daily living may receive help from family members, friends, paid helpers, community organizations, or government programs. The two main models of LTSS are home and community-based services (HCBS) and institutional care such as provided in nursing homes.11 HCBS include assistance at home and in other community settings such as an assisted living facility or adult day program.12

Home- and Community-Based Services

Many older adults in Central Indiana have problems maintaining their home and performing daily activities. They require support from home- and community-based services, such as Indiana’s Community and Home Options to Institutional Care for the Elderly and Disabled program (CHOICE)13 and the Medicaid Aged and Disabled Waiver (Waiver) program.14 The Waiver program provides home and community-based services (HCBS) to supplement informal supports for people who would require care in a nursing facility. Services offered under the CHOICE and Waiver programs include transportation, meals, personal care assistance with activities of daily living, home modifications, personal emergency response system, caregiver support, respite care, adult day services, and assisted living including memory care (Waiver only). In 2019-2020, individuals in Indiana receiving home- and community-based services under the publicly funded CHOICE or Waiver program experienced positive outcomes. Around 85% of these individuals felt supported enough to go home after discharge, had someone follow up after discharge, and knew how to manage their chronic conditions (see chart on right).

The Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) model, also offered by Indiana Medicaid, serves individuals ages 55 or older who are certified by the state to need nursing home care, able to live safely in the community with supports, and live in a PACE service area. PACE is responsible for delivering all medical and supportive services and coordinating the enrollee’s care under Medicare and Medicaid to help them maintain independence in their home as long as possible. Central Indiana has one PACE program serving residents of Johnson County and parts of Marion County.

Expansion of Home- and Community-Based Services

The Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA) is implementing reforms to the administration of long-term care under Medicaid with a goal to lower costs per person and deliver more care and services at home. Twenty-five other states have implemented similar reforms, called managed LTSS (mLTSS) programs.15

Nursing Home Care

Most nursing home care is custodial care such as help with activities of daily living (like bathing, dressing, using the bathroom, and eating). Many nursing homes are certified to provide skilled nursing care (like changing sterile dressings). Nursing homes that participate in Medicare or Medicaid are included in Nursing Home Compare, a rating system from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The rating system provides residents and their families with a summary of three dimensions of nursing home quality: health inspection results, staffing data, and quality measure data. The goal of the rating system is to help consumers make meaningful distinctions among high- and low-performing nursing homes. Among the many nursing homes in Central Indiana, approximately one of every four facilities currently has a five-star overall rating.

LTSS State Scorecard

The AARP Public Policy Institute periodically publishes the LTSS State Scorecard to provide state and federal policy makers and consumers with information they need to assess their state’s performance across multiple dimensions and indicators, learn from other states, and improve the lives of older adults, people with disabilities, and their families.18 Compared to the 2017 LTSS State Scorecard, Indiana’s overall ranking in 2020 was up to 44 from 51, and Indiana improved on indicators under two of the five dimensions: affordability and access (Indiana ranks 41) and quality of life and quality of care (Indiana ranks 19). Indiana ranks lowest (51) in support for family caregivers. For the dimension of choice of setting and provider, Indiana ranks in the bottom quartile (48) receiving particularly low scores for a) the percentage of Medicaid and state LTSS spending for HCBS vs. nursing home care, b) the percentage of Medicaid LTSS users receiving HCBS vs. nursing home care and c) adult day services supply. Planning for the next LTSS State Scorecard is underway, and will provide updated data covering the impact of the pandemic.

Low-Income and Other Vulnerable Older Adults

Older adults in Central Indiana have concerns about the expense associated with health care access, eligibility for Medicaid (e.g., “making too much money” to be eligible), inadequate health care coverage by Medicaid and Medicare, and cost of medications.19 See the Financial Stability section of the report for additional discussion.

Medicare and Medicaid are separate government-run health insurance programs serving two different populations. While Medicare provides health coverage to people age 65 years and older and people with disabilities, Medicaid provides health coverage to low- or very low-income individuals. Individuals who are eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid benefits, referred to as “dually eligible,” make up about 17 percent of total Medicare enrollment.20

Dually eligible individuals tend to have more chronic medical conditions and greater levels of physical disabilities and mental illness than persons with Medicare only., In addition, those who are dually eligible visit the emergency department (ED) and are hospitalized at more than twice the rate of those that have Medicare only.21 22 Nationally, the proportion of dually eligible beneficiaries of color increased from 41 percent in 2006 to 48 percent in 2018.23 In Indiana, approximately 80% of those dual eligible are White while 15 percent are Black, which is disproportionate to the total White and Black population.24

Hospital readmissions are often avoidable and may indicate a lack of coordination of medical care, or inadequate follow-up after patients leave the hospital. In 2020, the 30-day all-cause readmission rate for 65 to 74-year-olds in Indiana was 16 percent, equal to the U.S. rate. Indiana and U.S. rates have been steady since at least 2015.25

Older adults with dementia26 are also known to have higher hospitalization rates than those without dementia. A study at Eskenazi Health, a health care system in Indianapolis, demonstrated that older adults with dementia had more than twice the number of hospital admissions and care transitions compared to older adults without dementia.27

Local providers also expressed concern about the barriers experienced by the older adult LGBTQ+ population, who experience difficulties finding and accessing basic health care in Indiana for a variety of reasons. First, there is a limited presence of health care providers who specialize in LGBTQ+ specific health care. This is particularly the case for transgender people who struggle to find health care practitioners with knowledge regarding medical transition. Furthermore, one LGBTQ+ informant expressed concern regarding accessibility of general health care needs28 because of visible discomfort on the part of the health care provider. This person’s experience aligns with findings in the research literature.29 30 To learn more, see “Highlighting Equity” on disparities in health care access and quality for LGBTQ+ older adults.

Health Care Access and Quality Considerations for LGBTQ+ Older Adults

Compared to their non-LGBTQ+ peers, LGBTQ+ older adults experience higher rates of disability, poor physical health, and psychological distress.31 Using the social-ecological framework,32 we highlight some factors that can influence LGBTQ+ healthcare access and outcomes in Central Indiana.

Interpersonal factors:

Fear of disclosing sexual orientation or gender identity:

Many LGBTQ+ older adults experience fear or bias when disclosing their LGBTQ+ status to healthcare providers. One national study found that 15 percent of LGBTQ+ older adults were fearful about accessing health care services outside of the LGBTQ+ community, and nearly one quarter had not revealed their sexual orientation or gender identity to their primary care provider.33 Many LGBTQ+ older adults grew up in a time where non-heteronormative behavior could result in imprisonment, violence or loss of freedom, which led many to hide their sexual orientation or gender identity from others, including health providers.

Provider bias:

Providers can also demonstrate negative behaviors toward LGBTQ+ older adults, further demotivating these individuals to self-disclose their sexual orientation or gender identity. These negative behaviors of healthcare providers can either be intentional, such as refusing care or joking about the patient with other staff members, or unconscious, such as assuming that the patient’s married partner is of the opposite sex. LGBTQ+ older adults’ non-disclosure of their sexual orientation or gender identity may cause adverse health outcomes, such as a delay in diagnosing significant medical issues.34

Organizational factors:

Lack of LGBTQ+-inclusive health services:

Another factor that influences LGBTQ+ older adults’ health care in Central Indiana is the lack of guidelines and services for LGBTQ+ care in healthcare systems. The Human Rights Campaign’s Healthcare Equality Index 2020, which evaluates healthcare facilities’ policies and practices on LGBTQ+ patient inclusion and equity, only designated two Central Indiana healthcare facilities, Eskenazi Health and the VA Richard L. Roudebush Medical Center, as “LGBTQ+ Healthcare Equality Leaders.” This designation means that these facilities have LGBTQ+-inclusive policies around patient and employee non-discrimination and family visitation, provide LGBTQ+- specific patient services and support, and engage with the LGBTQ+ community through initiatives, events, or marketing.35 In contrast, three healthcare facilities in Central Indiana do not have an LGBTQ+-inclusive patient nondiscrimination policy, and one does not have an equal visitation policy for family members.36

Limited medical education inclusive of LGTB+ issues:

Another organizational concern is the lack of education inclusive of LGBT+ people provided in U.S. medical schools. A 2018 report from the Association of American Medical Colleges found that while three quarters of medical schools included some LGBTQ+ health themes in their curriculum, roughly half said that this education consisted of three or fewer lectures, group discussions or other learning activities.37 This lack of comprehensive medical education leaves many providers feeling inadequately trained to care for their LGBT patients. A 2018 survey of over 600 medical students found that 80% of respondents felt “not competent” or “somewhat not competent” in treating LGTBQ+ patients.38

Policy factors:

Lack of healthcare policies that explicitly protect LGTB+ individuals:

The lack of health care policies that explicitly protect LGTB+ individuals has a negative effect on this population. For example, Indiana’s Medicaid program has no explicit policy for transgender health coverage and care, which can create barriers to health care for transgender people receiving Medicaid in the state. In contrast, 23 states, plus Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia currently have an explicit policy for transgender health coverage and care in their Medicaid programs. Additionally, 24 states and the District of Columbia have laws preventing health insurers from “explicitly refusing to cover transgender-related health care benefits.” Indiana has not passed these protections.39

- Vincenzo Atella et al., “Trends in Age-related Disease Burden and Healthcare Utilization,” Aging Cell 18, no. 1 (February 2019), https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12861

- Community Assessment Survey for Older Adults TM. National Research Center Inc., 2021. https://cicoa.org/news-events/research/casoa/.

- “Geriatricians,” accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.advisory.com/Daily-Briefing/2020/01/21/geriatricians.

- “Bowen Center Information Portal,” accessed April 18, 2022, https://bowenportal.org/index.php/indiana-physician-workforce/.

- John W. Rowe, “The US eldercare workforce is falling further behind,” Nature Aging 1, 327-329 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-021-00057-z

- Thirty-five key informant interviews with caregivers and service providers were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. Public and not-for-profit sector leaders and service providers who are knowledgeable about service systems and issues pertaining to older adults in Central Indiana were identified and interviewed as key informants during report preparation.

- “What Is an Age-Friendly Health System? | IHI – Institute for Healthcare Improvement,” accessed January 25, 2021, http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx.

- “Current Number of Board Certified Geriatricians by State 8 1 19.Pdf,” accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Current%20Number%20of%20Board%20Certified%20Geriatricians%20by%20State%208%201%2019.pdf.

- Rowe, “The US eldercare workforce is falling further behind”

- “What Is the Lifetime Risk of Needing and Receiving Long-Term Services and Supports?,” ASPE, April 4, 2019, https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/what-lifetime-risk-needing-and-receiving-long-term-services-and-supports.

- “LTSS Overview | CMS,” accessed January 27, 2021, https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/American-Indian-Alaska-Native/AIAN/LTSS-TA-Center/info/ltss-overview.

- “Home & Community Based Services | Medicaid,” accessed January 27, 2021, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/home-community-based-services/index.html.

- CHOICE is an acronym for the program’s full name Community and Home Options to Institutional Care for the Elderly and Disabled. The CHOICE program is administered through Indiana’s 16 Area Agencies on Aging. The CHOICE program provides home- and community-based services to assist individuals in maintaining their independence in their own homes or communities for as long as is safely possible.

- Indiana Medicaid pays for services for individuals who choose to remain in their home as an alternative to receiving services in an institution, such as a nursing facility. These services are referred to as home and community-based services. These programs are intended to assist a person to be as independent as possible and live in the least restrictive environment possible while maintaining safety in the home.

- Indiana Family and Social Service Administration. Managed Long-Term Services and Supports. Accessed May 13, 2022, https://www.in.gov/fssa/long-term-services-and-supports-reform/managed-long-term-services-and-supports/

- Indiana Family and Social Service Administration. Managed Long-Term Services and Supports Stakeholder Update. November 3, 2021. Accessed May 13, 2022, https://www.in.gov/fssa/long-term-services-and-supports-reform/files/mLTSS-Design-Book-Presentation-11.3.21.pdf)

- ASHP. Capitated & Risk Sharing Models FAQ. July 2016. Accessed May 13, 2022, https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/pharmacy-practice/resource-centers/ambulatory-care/capitated-and-risk-sharing-models-faq.ashx

- “LTSS 2020 Short Report PDF 923.Pdf,” accessed January 25, 2021, http://www.longtermscorecard.org/~/media/Microsite/Files/2020/LTSS%202020%20Short%20Report%20PDF%20923.pdf.

- Nine focus groups with older adults were conducted during 2019 and 2020 to collect input on issues facing the older adult population in Central Indiana. The focus groups composed of older adults were assembled with the identification and recruitment assistance of community service providers. These focus groups were conducted by researchers, in person prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and by Zoom after the pandemic began. The questions asked of the focus group participants were discussed and agreed upon by research faculty and staff.

- Dual Eligible. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.kff.org/tag/dual-eligible/.

- “Coordinating Physical and Behavioral Health Services for Dually Eligible Members with Serious Mental Illness,” Center for Health Care Strategies, December 11, 2019, https://www.chcs.org/resource/coordinating-physical-and-behavioral-health-services-for-dually-eligible-members-with-serious-mental-illness/.

- “Medicare-Medicaid Enrollee Information National, 2012,” 2012, 6.

- CMS, “Medicare-Medicaid Dual Enrollment 2006 through 2018,” Data Analysis Brief (Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services, September 2019), https://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-Office/DataStatisticalResources/Downloads/MedicareMedicaidDualEnrollmentEverEnrolledTrendsDataBrief2006-2018.pdf.

- “Dual Eligible Beneficiaries by Race/Ethnicity,” KFF (blog), May 31, 2018, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/dual-eligible-beneficiaries-by-re/.

- “Explore Hospital Readmissions – Ages 65-74 in Indiana | 2020 Senior Health,” America’s Health Rankings, accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/senior/measure/hospital_readmissions_sr/state/IN.

- “What Is Dementia?,” Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia, accessed January 25, 2021, https://alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia.

- Christopher M. Callahan et al., “Transitions in Care among Older Adults with and without Dementia,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 60, no. 5 (May 2012): 813–20, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03905.x.

- For example, going to the doctor, getting an eye exam, etc.

- Utamsingh, P. D., Richman, L. S., Martin, J. L., Lattanner, M. R., & Chaikind, J. R. (2016). Heteronormativity and practitioner-patient interaction. Health communication, 31(5), 566–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2014.979975

- Bonvicini K. A. (2017). LGBT healthcare disparities: What progress have we made?. Patient education and counseling, 100(12), 2357–2361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.003

- Charles A. Emlet, “Social, Economic, and Health Disparities Among LGBT Older Adults,” Generations (San Francisco, Calif.) 40, no. 2 (2016): 16–22.

- University of Washington School of Medicine, “Social Ecological Model | Ecology of Health and Medicine,” August 12, 2017, https://blogs.uw.edu/somehm/2017/08/12/social-ecological-model/.

- Mary Beth Foglia and Karen I. Fredriksen-Goldsen, “Health Disparities among LGBT Older Adults and the Role of Nonconscious Bias,” The Hastings Center Report 44, no. 0 4 (September 2014): S40–44, https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.369.

- Foglia and Fredriksen-Goldsen.

- “HEI-2020-FinalReport.Pdf,” accessed January 25, 2021, https://hrc-prod-requests.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/resources/HEI-2020-FinalReport.pdf.

- “HEI Interactive Map – HRC,” accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.hrc.org/resources/hei-map.

- “Keeping Our Promise to LGBTQ+ Patients,” AAMC, accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/insights/keeping-our-promise-lgbtq-patients.

- “Medical Students Push For More LGBT Health Training To Address Disparities,” NPR.org, accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2019/01/20/683216767/medical-students-push-for-more-lgbt-health-training-to-address-disparities.

- “Movement Advancement Project | State Profiles,” accessed January 25, 2021, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/profile_state/IN.