Food Security and Resilience Among Older Adults in Central Indiana

Rachel Seymour and Unai Miguel Andres

Introduction

Food insecurity affects millions of older adults across the United States, impacting physical health, mental well-being, and social connectedness. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines food insecurity as limited or uncertain access to adequate food, disproportionately affecting vulnerable groups, including low-income seniors, rural populations, and people with disabilities. In Central Indiana, one in 10 older adults aged 55 and older faces food insecurity, with higher rates in urban areas like Indianapolis., One out of nine older adults aged 50 and older in Indianapolis experiences food insecurity.1,2 While the food insecurity rate among older adults in Indianapolis has declined since 2017, barriers such as transportation and geographic inequities persist.3

Food insecurity among older adults is best understood through its four dimensions: availability, accessibility, utilization, and stability. Availability refers to a community’s overall supply of food, which can be insufficient in food deserts. Accessibility involves the ability to physically reach and afford food. For many seniors, limited mobility, physical disabilities, and inadequate public transportation make grocery access challenging, particularly in areas known as food deserts. Food deserts are predominant in Marion County, particularly in areas around the Mid-North, Northeast Side, Far Eastside, Southwest Side, and Southside neighborhoods, as well as in Hancock County.1,4 These areas face systemic barriers to food access due to supermarket redlining, the historical phenomenon in which grocery chains avoid establishing stores in low-income or urban neighborhoods.1 Utilization includes having the skills, resources, and culturally appropriate food necessary to meet dietary needs, while stability refers to the consistency of food access over time. Older adults often experience instability due to health issues, income fluctuations, or social isolation.5

Addressing food insecurity among older adults requires a multi-tiered approach. At the national level, the Commodity Supplemental Food Program (CSFP) provides eligible low-income seniors with monthly food boxes that include essential items like grains, dairy, and canned fruits and vegetables, which supplement their diets with nutritious foods.6 Meals on Wheels, another crucial program, delivers meals directly to homebound seniors, addressing both nutritional needs and providing regular social interaction to reduce isolation.7 State-specific initiatives like the Senior Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program in Indiana offer coupons to eligible seniors to purchase fresh produce from local farmers, enhancing their access to fresh fruits and vegetables while supporting local agriculture.8

Regionally, Area Agencies on Aging (AAAs) play a central role in coordinating food assistance for seniors, particularly in underserved or rural areas. Many AAAs partner with local organizations to offer senior food box programs, organize pantry days specifically for older adults, and support congregate meal programs at senior centers. These programs meet nutritional needs and foster social engagement, helping to reduce isolation among seniors who may lack other forms of support. By establishing a network of food access points tailored to older adults, AAAs contribute to the resilience of aging communities, providing a critical foundation for navigating food insecurity in Central Indiana. Valliant et al. emphasize that Indiana’s rural older adults often rely on community-based food resources, such as senior centers offering congregate meals, to manage their food needs.9 These centers provide not only nutritional support but also a critical sense of community that reduces social isolation, a known risk factor exacerbating food insecurity.10

Social isolation compounds the food insecurity faced by many older adults. Studies have shown that loneliness and limited social networks restrict food access, particularly when family support is lacking or mobility is impaired.5,10 Isolation can also increase mental health challenges, creating additional barriers to food security. A resilience framework, which focuses on how individuals and communities adapt to adversity, offers a valuable perspective for understanding how older adults navigate food insecurity. The resilience framework has evolved to emphasize social resilience—the capacity of individuals to draw on social networks and community resources to meet basic needs and sustain well-being under challenging circumstances.11,12

Resilience addresses not only resource scarcity but also the strategies individuals employ to manage these limitations. Resilience involves both formal and informal support systems. Formal systems include structured programs like Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Meals on Wheels, and congregate meal sites at senior centers. These services are crucial for many older adults, yet barriers such as program eligibility, transportation issues, and lack of awareness can hinder their accessibility.9,13,14 Senior enrollment in supplemental nutrition programs like SNAP lags in Indiana, which ranks only 42nd nationally.1

Informal networks, like those created in senior centers, can mitigate barriers. Senior centers often function as third spaces—social environments that foster community ties and reduce isolation.15 For older adults, these spaces are critical not only for accessing food but also for creating supportive relationships that contribute to a sense of belonging and shared resilience.16

In Central Indiana, the resilience framework can help shift the focus from vulnerability to adaptation, highlighting the creative and resourceful ways that older adults manage food security challenges through community engagement and social connections. This study explores these dynamics by examining the lived experiences of older adults at a rural senior center in Central Indiana, aiming to understand the role of both formal food programs and informal support systems in promoting food security. By using a resilience-based approach, this research seeks to illuminate how community-centered interventions can support food security and enhance the effectiveness of food systems for older adults.

Social Isolation Factors

Persona

Mark & Lilly

Mid-70s

Attend local meal sites

Navigating through medical challenges

Mark and Lilly are new to the Senior Center. They started visiting after attending a welcome event and because it was located close to their home. They enjoy lunch at their local senior center and have recently begun traveling to Indianapolis for lunch at another senior center. They began making this trip because of a local community network who is helping them deal with a medical challenge. While caregiving for a brother who is navigating complicated health concerns, Mark and Lily are attending these two meal sites in hopes of networking and socialization. Although the congregate meal site in Indianapolis is farther away from their neighborhood meal site, it allows them to gain a greater social network with people going through similar medical challenges. This opportunity wouldn’t have been possible if they had not networked through the congregate meal program. Navigating these tough medical challenges and sharing advice in these spaces allows them to gather resources, find a shared sense of belonging, and practice food security through this network.

Personas are sketches of fictional people that represent real challenges and circumstances highlighted in this report. They are a useful way to imagine how these statistics impact the lives of individuals and families.

Research Methods & Results

This study used qualitative interviews to explore the food security experiences of older adults at a rural senior center in Central Indiana. Spatial mapping was also conducted to identify emergency food access points specific to older adults (i.e., food pantries with senior shopping days and senior congregated meal sites) across Central Indiana, and the average travel time to the closest meal site for residents in each Central Indiana block group. Block groups, shown in the accompanying map, are geographic units defined by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The spatial analysis identified a total of 26 food pantries in Central Indiana that offer specific shopping days for seniors, along with 23 sites providing congregate meals tailored to older adults. Most of the pantries (24 out of 26) host senior shopping days once a month, usually open for a limited window of two to three hours. In contrast, congregate meal sites offer more frequent access, with 19 out of the 23 sites serving meals from Monday through Friday, supporting both nutritional needs and social engagement.

Travel Time to Senior Food Pantries and Meal Sites

The qualitative part of this study involved eleven (11) semi-structured interviews with older adults at a senior center at around the time the congregational meal site was being served. The interviews were guided by questions about their food access strategies, participation in food programs, and the role of the senior center in their daily lives. The decision to focus on a rural senior center was driven by the need to highlight perspectives often underrepresented in food security research, which frequently concentrates on urban areas like Marion County. Rural older adults face unique challenges, including longer travel distances to food resources and fewer public transportation options, as noted in the State of Aging Report’s chapter, Transportation.3 Additionally, rural settings often rely more heavily on social networks and informal support systems to address challenges (including food insecurity), emphasizing the importance of understanding these dynamics.3 This approach also addresses the geographic disparities highlighted in the State of Aging in Central Indiana report, such as food deserts in Hancock County and other rural areas, to offer a more comprehensive understanding of food access inequalities.3

Participants interviewed were primarily females of retirement age or older; however, they varied in degree of social connectivity, allowing for a diverse exploration of experiences. The interviews revealed common themes that reflect the senior center’s role as a trusted third space where members access food resources, socialize, and create informal caregiving networks. This concept of “third spaces” refers to community settings that foster connection and support outside the home, creating essential support networks for seniors who may otherwise face isolation.15,17

“If someone doesn’t show up and you’re not here for a couple of days and you didn’t say anything to anybody, then usually somebody will come check on ya.”

– Interview with author, 2024

One key finding was the strong sense of belonging and interdependence that seniors expressed regarding the center. For many, the center was a “neighborhood” where they knew one another’s routines and health. For example, members shared that if someone missed a few days, others would check in to ensure their well-being. This sense of mutual care extended to food sharing, with individuals frequently exchanging meal components, produce from the center’s community garden, and surplus items. “Maggie”, a member known for helping others, would collect unused food for a friend experiencing food insecurity. Another participant noted that she “comes for the meal, stays for the social hour,” underscoring the value of the center as a space that simultaneously addresses nutritional needs and reduces isolation (“Donna,” Senior Center Community Member, Interview with author, October 2024)

“I haven’t driven since I had the stroke, so when I need transportation, [the public bus] helps. Today they’re going to pick me up from here [the Senior Center], and take me to Walmart, then pick me up from Walmart and take me home.”

– Interview with author, 2024

Another key finding from the study was older adults using these centers as a resource hub. Aside from the numerous resources made available through community programming, there were also resources available through mutual aid. Multiple participants experienced health challenges and utilized the Senior Center as a space to network with others experiencing similar challenges. This gathering of resources allowed them to provide caregiving tips to better support one another through shared health experiences.

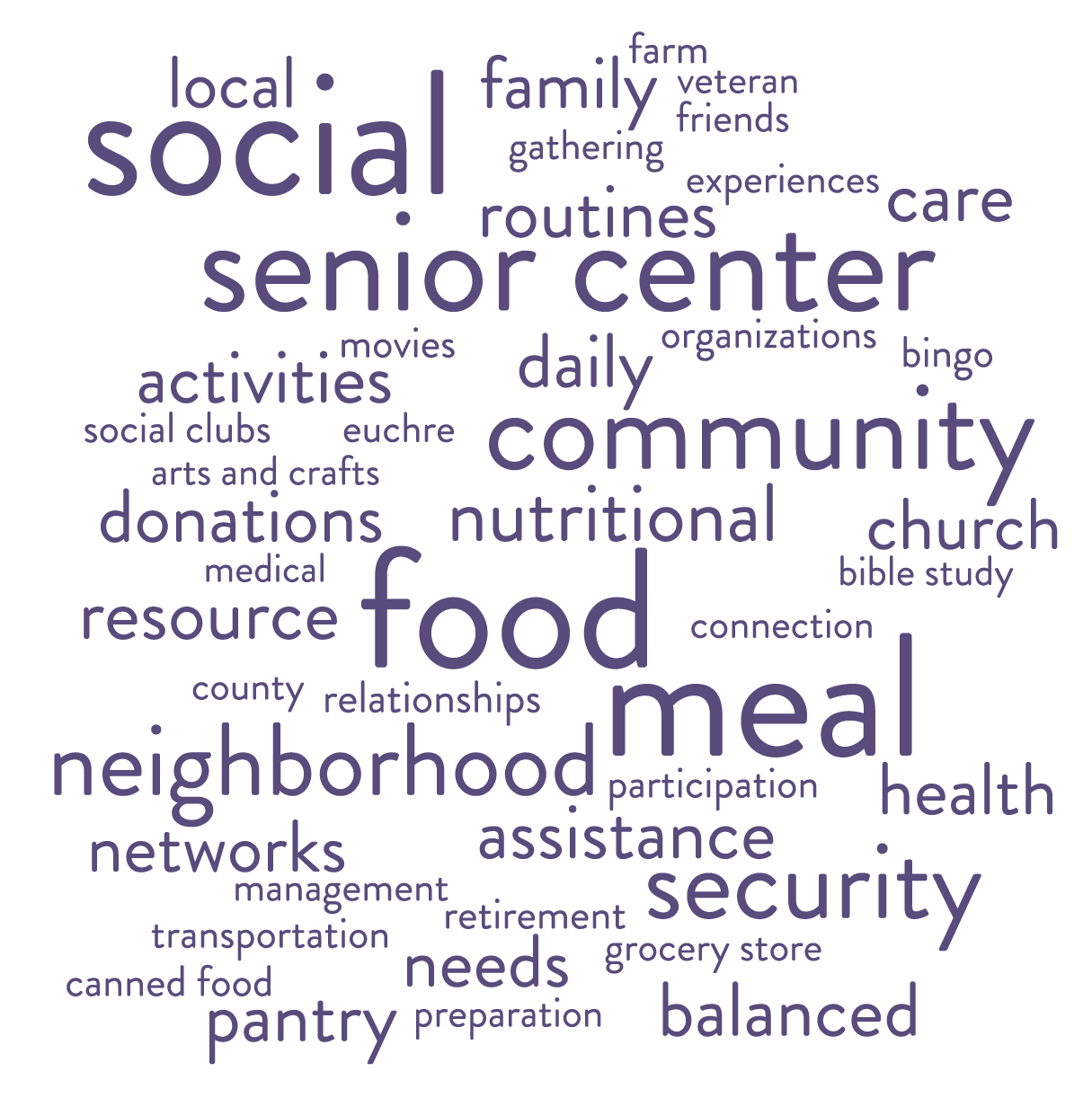

Words Related to Senior Centers

“As a group, we go to Sam’s Club for socializing and shopping. We all like hot dogs, so after we shop, we get a hot dog there at Sam’s Club. We get to socialize with each other and catch up, you know, just have fun.”

– Interview with author, 2024

Participation in programs like Produce for Better Health, which provides bi-monthly fresh produce, was also common. Seven out of 11 participants regularly engaged with this program, reporting that it improved their access to fresh fruits and vegetables. Other popular programs included congregate meals and community potlucks, which participants described as vital for both physical nourishment and social engagement. Some members enjoyed decorating their plates with shared condiments or bringing in snacks to share, creating an atmosphere of abundance and community support. Together, these findings underscore the center’s role in facilitating food security, social connection, and resilience for aging adults in Central Indiana.

Persona

Maggie

Late 70s

Senior center leader

Helps friend who’s navigating food insecurity

Maggie is a long-time member of the Senior Center. She has spent the majority of her retirement attending and planning daily activities at the center. The center has a membership activities board which advises the executive director on the activities which should be planned over the next few months. These events are generally informed by individuals’ preferences (arts and crafts based on holidays) and community engagement with a variety of activities (for example a need for an educational class on caregiving if there is an uptick in need), mixed with longstanding activities (such as Bingo or Euchre). Maggie’s presence at the center is known to many and a majority of the other members look to her leadership for answering common questions in moments of confusion. During lunch at the center one day, Maggie was explaining the different nutritional programing available through the center and how it contributes to the members feeling more food secure. In the middle of our conversation, a table mate asked, “Maggie, would your friend on social security eat my fruit? I don’t like canned pineapple.” “I’m not sure, but I’ll take them anyway!” Maggie said as she accepted the fruit. She then explained to me how her table mates know she has a friend who is living on social security and experiencing food insecurity. Although Maggie was not navigating food insecurity herself, she was helping a friend feel more food secure by navigating the food systems she knows and is comfortable with. This includes purchasing 25-cent bread for the friend, gathering unused food, and sharing produce from the garden from time to time. This shows the resiliency of older adults utilizing various community food networks to serve those in need.

Discussion

The findings emphasize the multifaceted role of senior centers in addressing food insecurity among older adults. As essential third spaces these centers provide not only meals but also critical social interactions that foster resilience and a sense of belonging. This aligns with existing literature suggesting that third spaces like senior centers, libraries, and community gardens foster social cohesion and a sense of belonging, which are critical for well-being, particularly among isolated populations.15,16,18 For older adults in Central Indiana, this sense of belonging reduces feelings of loneliness and isolation, known factors that exacerbate food insecurity and mental health challenges.10 Prior research has revealed that nearly one-quarter of seniors in Central Indiana experience social isolation, with rural seniors facing compounded barriers due to geographic dispersion and fewer community resources.5 Senior centers help bridge these gaps by serving as consistent gathering places with accessible programs that strengthen community bonds and address multiple dimensions of well-being, positioning it as a vital resource in food-scarce environments where older adults can build networks of mutual support.

The lack of senior-specific food resources in certain regions, such as Hancock County, highlights a significant geographic disparity in food access. Seniors in these underserved areas may face additional barriers, particularly if they lack reliable transportation, underscoring the need for more evenly distributed food support services across Central Indiana. Drive times to food resources, which can be as long as 35 minutes for meal sites and 45 minutes for pantries, illustrate significant barriers for seniors without transportation. These extended travel times highlight the need for additional resources closer to underserved communities to improve food access and reduce transportation burdens.

The resilience framework, as applied here, illustrates how older adults adapt to and navigate limited food access through a mix of formal and informal support networks.11 By leveraging these networks, seniors exercise agency in managing their food security. Community gardening, programs like Produce for Better Health, and meal-sharing rituals not only increase their access to food but also create interdependent networks of care. This is evident in Maggie’s practice of gathering extra food for her friend, reflecting a “neighborhood-like” reciprocity that is characteristic of resilience-driven adaptations.16 These mutual support practices highlight how resilience in food security is a social process, built on relationships and shared resources rather than isolated actions; however, structural barriers such as complex enrollment procedures, cultural limitations, and transportation gaps hinder broader access to food.3 Black and Hispanic participants have noted additional barriers in accessing culturally appropriate foods, aligning with findings that food assistance programs are often underutilized in communities of color due to a lack of tailored options and historical distrust.19 Simplifying program requirements, adding additional meal sites, and incorporating culturally relevant food choices could increase program engagement, particularly in marginalized communities. Expanding caregiver resources could also strengthen food security for seniors, as caregivers often navigate these systems on behalf of older adults with mobility or health limitations.

These insights suggest that enhancing senior centers and other third spaces could significantly improve food security and social well-being among older adults. Policies that support senior centers as multifunctional spaces can amplify their role in promoting resilience, making them more than meal sites but hubs of social interaction, emotional support, and resource sharing. Programs that integrate nutrition with community-building are especially effective, as they foster a sense of purpose and belonging among aging adults, mitigating the isolation that often accompanies aging.15,17

Senior centers not only address the immediate need for food but also can create environments of resilience where older adults can maintain their autonomy, contribute to one another’s well-being, and engage in adaptive, community-centered food security strategies. This resilience-centered approach highlights the potential of senior centers to serve as a model for addressing food insecurity in aging populations, emphasizing the importance of social networks and culturally competent, accessible food programs as integral to the health and vitality of older adults in Central Indiana.

Conclusion & Recommendations

To address food access disparities, particularly in underserved areas such as Hancock County, future initiatives could consider establishing additional senior-focused food resources in rural regions with limited options. Reducing travel distances to supplemental food resources could alleviate transportation burdens, making these services more accessible for seniors across Central Indiana.

This research highlights the vital role senior centers can play in fostering food security and resilience among older adults in Central Indiana. Acting as third spaces, these centers offer more than nutrition; they provide a sense of belonging, social support, and adaptive strategies that allow seniors to navigate limited food access. Through mutual aid, community gardening, and shared meal programs, older adults engage in a web of reciprocal relationships that both mitigate food insecurity and enhance well-being.

The findings suggest that holistic programming that integrates nutrition with community-building and social support could improve food security for aging populations. Simplifying access to food programs, creating culturally tailored options, and enhancing caregiver resources could further strengthen food resilience. The success of senior centers as social and nutritional hubs for older adults in Central Indiana underscores the potential for community-based, resilience-centered interventions to effectively address food insecurity. With policy and community support, senior centers can continue to evolve as essential resources for an aging population, ensuring that older adults have access not only to food but to the networks and support systems that are integral to their well-being. Policymakers and community planners could prioritize establishing new food resources in areas with limited or no access to senior-specific food programs to ensure equitable food access for all older adults.

Persona

Kelly

Early 80s

Uses public transportation

Connects with local social groups

Kelly recently moved into a four-generation household after having a stroke. Her daily care needs are taken care of by various family members, meanwhile she takes advantage of other community resources like public transportation. She attends many types of local social groups. One of her social groups meets at the local super store to socialize and shop together. Together they share a meal after shopping because these meals are affordable, convenient, and allows them to socialize regularly while running errands. Kelly also often meets her friends at the Senior Center. The Senior Center helps connect her with resources like filling out government paperwork and paperwork with the VA, which at times can be strenuous and confusing. Spaces like the Senior Center are a welcoming environment for Kelly.

Limitations & Future Research

This qualitative study had limitations. Specifically, the group sampled was limited in racial and cultural diversity. Majority of the perspectives gathered were from White, female, food-secure backgrounds. While qualitative sampling is limited to the perspectives of those willing to participate, it is also important to note that diverse perspectives are missing from this report which are needed to capture the full understanding of food security in Central Indiana.

Future research should expand the scope to include diverse urban, suburban, and rural sites, ensuring a more representative understanding of food security challenges across Central Indiana. Longitudinal studies will also be conducted to examine changes in food security and resilience over time, particularly as new interventions are implemented or as the needs of older adults evolve. Additionally, culturally tailored interventions addressing barriers faced by marginalized groups, such as Black and Hispanic communities, should be a key focus. Collaborations with policymakers could further support evaluations of outreach programs like SNAP and initiatives to enhance food access in rural settings, ensuring these efforts effectively meet the needs of Indiana’s aging population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Central Indiana Senior Center, their dedicated director, and active community members who participated in this study and shared their experiences surrounding food security.

The production of this research brief was made possible by the following Polis team members: Karen Comer, Project Director/Editor; Kayla Duncan, Project Coordinator; Alli Kraus, Graphic Designer; Katharine Brunette, Graphic Design Intern; Bonnie VanDeventer, Co-editor, and Allegra East, Proofreader.

- The Polis Center. (2023). State of Aging in Central Indiana: Food Insecurity (December). https://centralindiana.stateofaging.org/report-data/food-insecurity/

- Economic Research Service. (2024). Definitions of food security. USDA. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security#characteristics

- The Polis Center. (2023). State of Aging in Central Indiana: Transportation (November). https://centralindiana.stateofaging.org/transportation-2023/

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2006). Food Security (Policy Issue Brief 2). https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/faoitaly/documents/pdf/pdf_Food_Security_Cocept_Note.pdf

- The Polis Center. (2023). State of Aging in Central Indiana: Social Wellbeing. https://centralindiana.stateofaging.org/report-data/social-wellbeing/

- Food and Nutrition Services. (2021). 101 Fact Sheets (p. 21). US Department of Agriculture. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.343276

- Meals on Wheels of America. (2024). What we deliver: 2024 national spanshot (p. 2).

- Indiana State Department of Health. (n.d.). Senior Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program (SFMNP). https://www.in.gov/health/wic/farmers-marketsstands-information/#tab-686413-4-Senior_Farmers__Market_Nutrition_Program__SFMNP_

- Valliant, J. C. D., Burris, M. E., Czebotar, K., Stafford, P. B., Giroux, S. A., Babb, A., Waldman, K., & Knudsen, D. C. (2022). Navigating Food Insecurity as a Rural Older Adult: The Importance of Congregate Meal Sites, Social Networks and Transportation Services. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition, 17(5), 593–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2021.1977208

- Burris, M., Kihlstrom, L., Arce, K. S., Prendergast, K., Dobbins, J., McGrath, E., Renda, A., Shannon, E., Cordier, T., Song, Y., & Himmelgreen, D. (2021). Food Insecurity, Loneliness, and Social Support among Older Adults. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition, 16(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2019.1595253

- Berkes, F., & Ross, H. (2013). Community Resilience: Toward an Integrated Approach Community Resilience: Toward an Integrated Approach. Society & Natural Resources, 26(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2012.736605

- Adger, W. N. (2000). Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Progress in Human Geography, 24(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913200701540465

- Dean, O., Gothro, A., Navarro, S., & Bleiweiss-sande, R. (2022). Participation: Who Are the Eligible but Unenrolled ? (July).

- Gibson, C. A., Valentine, H. A., Mount, R. R., Gibson, C. A., Valentine, H. A., & Mount, R. R. (2025). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Among Older Adults in Missouri: Challenges

Applying for and Using SNAP Benefits. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 44(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2024.2448960 - Oldenburg, R. (1999). The great good place: Cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a community. Da Capo Press.

- Aday, R. H., Wallace, B., & Krabill, J. J. (2019). Linkages Between the Senior Center as a Public Place and Successful Aging. Activities, Adaptation and Aging, 43(3), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2018.1507584

- Wiles, J. L., Wild, K., Kerse, N., & Allen, R. E. S. (2012). Resilience from the point of view of older people: ‘There ’ s still life beyond a funny knee ’. Social Science & Medicine, 74(3), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.005

- The Polis Center. (2023). State of Aging in Central Indiana: Aging in Place. https://centralindiana.stateofaging.org/report-data/aging-in-place/

- Sansom, G. (2021). Disparate access to nutritional food; place , race and equity in the United States. BMC Nutrition, 4–9.